The History of the Discovery of Ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosaurs ("fish lizards") are an extinct group of aquatic marine reptiles

(not fish nor lizards), who belong to the order known as

Ichthyosauria.

Ichthyosaurs, lived in the Mesozoic era from the Early Triassic to the Late Cretaceous,

about 250 million to 90 million years ago and were contemporaries of the Dinosaurs.

However, they died out about 30 million years before the extinction of Dinosaurs.

Ichthyosaurs are closely related to another aquatic group of reptiles the plesiosaurs.

Both groups share some features of the skull (retaining the upper temporal fenestrae – openings

in the skull behind the eye socket between the post-orbital and squamosal bones).

They are derived from a diapsid reptile ancestor and at some point in the lineage secondarily

lost the lower set of temporal fenestrae.

[R1a]

(

Fenestrae are small opening behind the orbit,

under which the post-orbital and squamosal bones articulate.)

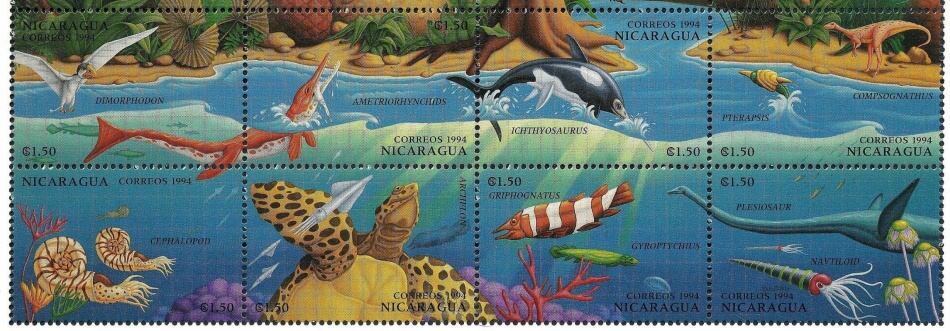

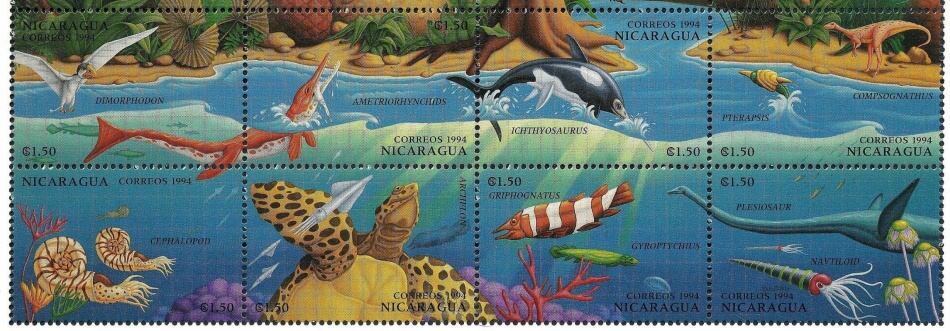

Prehistoric life in Mesozoic era on stamps of

Nicaragua 1994. MiNr: 3372-3387, Scott: 2041.

Ichthyosaur is on the third stamp in the third row from the top.

Prehistoric life in Mesozoic era on stamps of

Nicaragua 1994. MiNr: 3372-3387, Scott: 2041.

Ichthyosaur is on the third stamp in the third row from the top.

|

Malaysia 2020, part of Marine Life Definitive Series stamps set.

MiNr.: 2556, Scott:

|

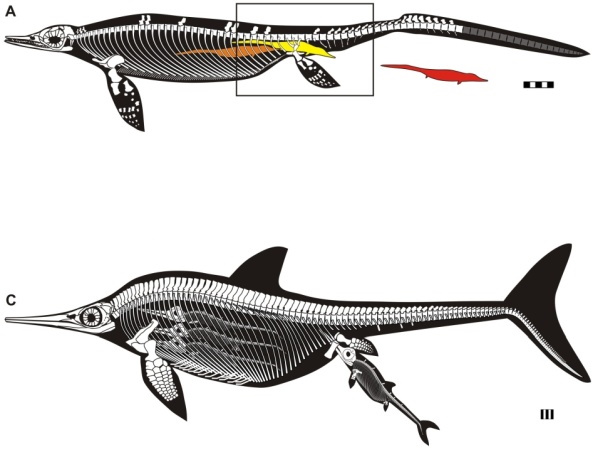

The ichthyosaurs through

convergent evolution evolved a fish-like

body adapted for living in water exclusively.

By the end of the Triassic, ichthyosaurs had adapted to fully aquatic conditions with

streamlined bodies, fins, and a sickle-shaped tail.

The fins and tail were used to propel the animals through the water when swimming.

They were unable to return to land – and hence were unable to lay eggs on land like modern sea turtles do today.

[R1]

Unlike most prehistoric and living reptiles, ichthyosaurs carried their live embryos inside their bodies until birth.

The young were laid side by side within their mother’s womb with their snouts pointing towards their mother’s head.

It would be reasonable to assume that the ichthyosaurs had developed some form of placenta for the care of their young.

However, this hypothesis cannot be tested directly as the preservation of the fossils does not preserve enough detail.

Ichthyosaurs could, like some modern reptiles, have been ovo-viviparous, retaining the eggs in the body until they had fully developed.

The embryos would then have fed from the yolk of each egg.

Just as they would if the egg had been laid on land.

Over 100 fossils of ichthyosaur mothers with embryos have been found to date. Some of these mothers had up to 11 babies!

A new study confirms that the first ichthyosaur new-born came out snout first, possibly to avoid suffocation during birth.

Over time, ichthyosaurs become more adapted to giving birth in water – with younger, more advanced genera exhibiting

new-born being born tail first, similar to modern dolphins and other cetaceans.

It is thought that this adaptation developed to allow the new-born to more quickly swim to the water surface to breathe air.

[R3]

|

|

Ichthyosaur (Temnodontosaurus) eye with Sclerotic Ring.

Image credit: Wikipedia.

|

The eyes of ichthyosaurs were very large in relation to their body length and surrounded by a ring-shaped,

bony reinforcement, the Sclerotic Ring, which occurs in many vertebrates.

It lay within the eyeball tissues, as in modern birds for example.

The Sclerotic Ring probably served to hold the shape of the flat eyeballs of the ichthyosaurs under

changing pressure conditions as they swam to deeper water depths.

The largest eye found in an ichthyosaur is also the largest eye of any vertebrate animal – living or extinct,

both absolute and relative.

The largest recorded eye (

Temnodontosaurus) was bigger than a football and had a diameter of 26.4cm.

Such huge eyes allow high light sensitivity and visual acuity at great depths, suggesting that ichthyosaurs

were deep-diving hunters, like some modern whales.

Some studies suggest that ichthyosaurs may have been homeothermic (warm-blooded animals),

which would have allowed ichthyosaurs to compensate for the colder water temperatures at depth when diving.

In addition, it is likely that these animals developed the ability to hold their breath for long periods of time

like modern whales.

Rough estimates suggest that ichthyosaurs could have held their breath for 20 minutes while diving up to

600 meters depth or more.

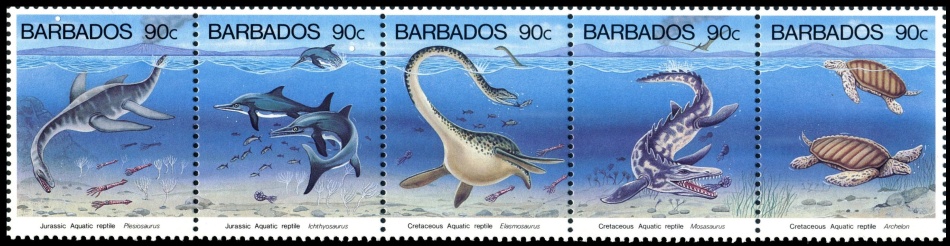

Some fossils of ichthyosaurs contain remains of their prey in the stomach region.

It looks like the favorite food of the most of ichthyosaur species were fish and tentacles of ammonites and belemnites.

Remains of sea turtles, birds and even other marine vertebrates have been found in the stomach of big ichthyosaur species,

as

Temnodontosaurus for example.

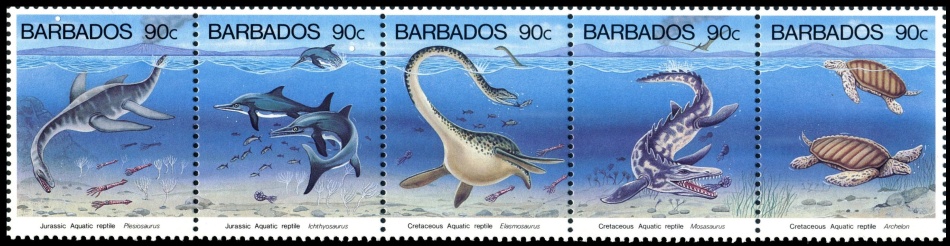

Ichthyosaurs and other prehistoric marine reptiles on the hunt.

Barbados 1993, MiNr.: 835-839, Scott: 855

Ichthyosaurs and other prehistoric marine reptiles on the hunt.

Barbados 1993, MiNr.: 835-839, Scott: 855

The largest species recorded to date is Shonisaurus sikanniensis, which was collected from British Columbia,

Canada, and described in 2004.

This giant ichthyosaur lived about 215 million years ago and has an estimated length of 21 meters.

Some fragmental finds of other specimens collected in Aust Cliff in Gloucestershire, in 2016,

UK suggest that ichthyosaurs were, probably, able to grow even longer

and reach a length of about 25-26 meters, around the average size of a blue whale. [R1d, R1e]

Although

Ichthyosaurs and Dolphins have a similar shape and have many common features,

they are completely different animals.

-

Ichthyosaurs are euryapsids, a group of reptiles derived from

a diapsids reptile ancestor.

Unlike Ichthyosaurs, Dolphins are derived from a mammalian ancestor and evolved after the Ichthyosaurs had died out.

-

Ichthyosaurs rely on their big eyes to hunt for the prey, while Dolphins rely on echolocation.

Computed tomography scan on the skull of some ichthyosaur species (Platypterygius for example),

shows that the inner ear were too thick to detect sound vibration and ichthyosaurs didn't have a device

to generate and focus returned sound. (radiographer George Kourlis and paleontologist Ben Kear, 2001)

-

Ichthyosaur tails were vertically oriented, with only the lower lobe supported by the caudal vertebral column,

therefore they swam in a fashion similar to eels – beating their tails side to side.

Dolphins have a horizontal tail and have a totally different locomotion style: they move their tail

up and down to swim through the water.

-

Ichthyosaurs have hind-fins, probably used for maneuvering,

while Dolphins have secondarily lost their hind limbs and so do not have a structure to support hind fins.

-

Ichthyosaurs evolved backbones that look like a stack of hockey pucks.

Backbones of Dolphins have different shape.

Similar body shape or features evolved by different groups of animals that lived in similar environments is called

Convergent Evolution.

Due to competition with other marine predators like

Kronosaurus, a pliosaur, ichthyosaurs

changed their diets to smaller prey.

This giant prehistoric animal was up to 9 meters long and lived in the Lower Cretaceous time, about

125 to 100 millions of years ago.

The strong jaw, of 2.4 meter long, with strong teeth, up to 37cm long, suggest that

Kronosaurus preferred

to not eat fish but instead preyed upon larger animals including ichthyosaurs.

|

|

|

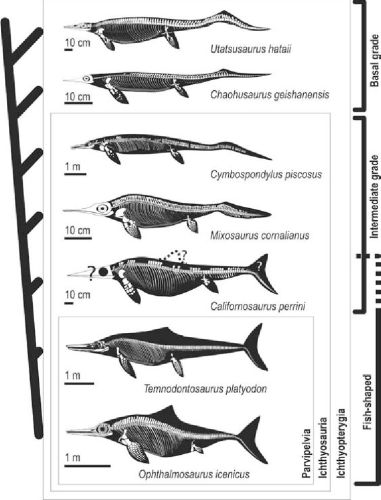

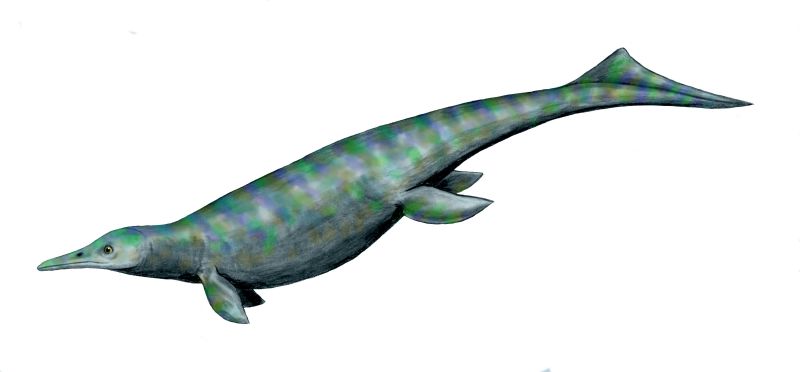

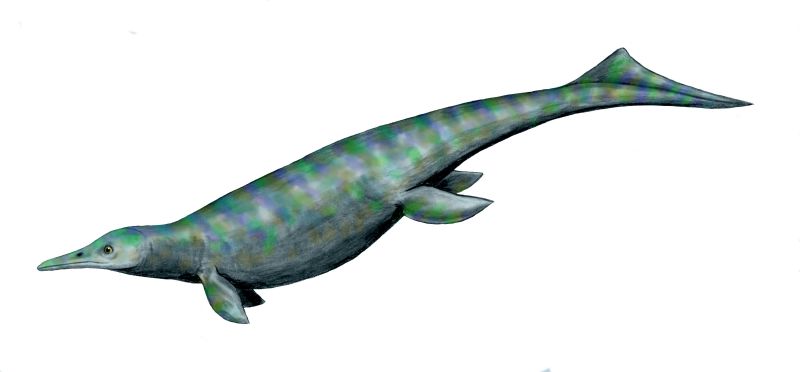

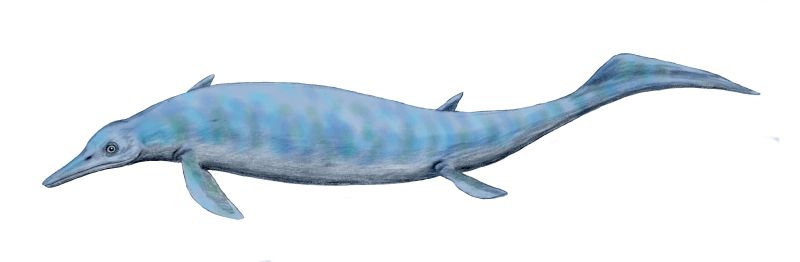

Reconstruction of Utatsusaurus (top) and Chaohusaurus (bottom) by Nobu Tamura.

|

The origin of the ichthyosaurs stayed in the dark for a long time.

The first fragmental fossils of Triassic ichthyosaurs were discovered in 1927 in Japan.

Without complete skeletons of the very first ichthyosaurs, paleontologists could merely

speculate that they must have looked like lizards with flippers.

Two primitive ichthyosaur skeletons were discovered in 1982.

They were uncovered by Japanese paleontologists from Hokkaido University who excavated them

from the northeastern coast of Honshu, the main island of Japan and named them Utatsusaurus.

This animal is one of the earliest members of the ichthyosaur tribe, lived in Triassic period,

approximately 250 million years ago.

It took almost 15 years for Dr. Nachio Minoura and his colleagues to clean these bones,

by delicately picking the rock away using fine carbide needles under a microscope.

In 1995, the exciting moment came that Utatsusaurus [R2]

was really a long-snouted lizard with fins. [R1c]

At about the same time, another basal ichthyosaur was reported from China - Chaohusaurus.

Chaohusaurus [R2] did not have the dolphin-like form of later ichthyosaurs;

it had a more lizard-like appearance with an elongated body.

These proportions were not caused by the large number of vertebrae, which included about 40 pre-sacral vertebrae,

instead the elongate length of the body is due to the elongation of each individual vertebra.

The animal’s head was short being roughly a third the length of the trunk, with a narrow-pointed beak and large eye sockets.

[R1]

Although the origin of the ichthyosaurs had only been clarified in 1995,

articulated skeletons of ichthyosaurs had been known to science since the mid-18th century.

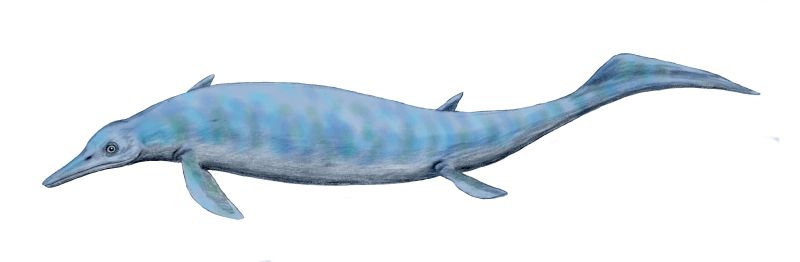

The first recognized, partial, skeleton of an ichthyosaur was discovered in Lyme, England in 1811-1812 by the

twelve-year-old Mary Anning and her elder brother Joseph.

In 1811 Joseph spotted a “crocodile” skull in the cliffs near his home in the seaside

community of Lyme Regis, England.

Nearly 12 months later, his sister, Mary Anning, who had been told where the skull was found,

discovered the torso of the same specimen.

The specimen was dug out by some workmens hired by the family.

The Western Flying Post reported on 9 November 1812:

“

A few days ago, immediately after the late high tide,

was discovered, under the cliffs between Lyme Regis and Charmouth,

the complete petrification of a crocodile, 17 feet in length, in a very perfect state.

It was dug out of the cliff nearly on a level with the sea,

about 100 feet below the surface of the earth.”

Mary Anning (1799-1847) was the early professional fossil collector, dealer, and paleontologist.

She became known around the world for finds she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel at Lyme Regis

in the county of Dorset in Southwest England.

Anning's findings contributed to changes in scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the history of the Earth.

[R4]

This fossil was purchased by local Lord of the Manor, Henry Henley, who owned much of Lyme and the cliff and beach where it was found.

The passed it to William Bullock’s Museum in Piccadilly, London where it created a sensation.

In 1819, Bullock auctioned his permanent collection of natural history and ethnographic specimens.

The fossil of Annings was bought at auction in London by the British Museum and it still

on display in the Natural History Museum in London (BMNH R.1158).

Even original label "Purchased from Bullock's Museum, Piccadilly, in 1819" survived on the fossil.

Nowadays it is assigned to

Temnodontosaurus platyodon specimen.

[R2]

|

|

|

Sir David Attenborough presents the ichthyosaur stamp of Great Britain (2013, MiNr: 3527, Scott: 3229).

The ichthyosaur fossils on display behind Sir Attenborough were discovered by siblings Joseph and Marry Anning in 1811-1812 and 1823.

Image credit: Bridport News

|

The partial skeleton of an Ichthyosaur discovered by Joseph and Mary Anning in 1811-1812 in the vitrine (bottom) of NHM UK, London.

the photo made by the author on September 29th, 2025.

Specimen Nr.: BMNH R1158.

It is assigned to Temnodontosaurus platyodon today.

|

The fossil discovered by Joseph and Mary Anning was not the first fossil of ichthyosaur

collected in England, but was the first fossil brought to scientific attention,

recognized as remains of a new animal and it was the first ever scientific description of

an ichthyosaur (Sir Everard Home 1814).

Many museums across England had, fossils of Ichthyosaurs, but were misinterpreted

and assigned to crocodiles, fish, lizard or as "sea-dragons".

For example:

- In 1766, 12 meters about (40 feet) ‘Young Whale’ had been discovered at Weston near Bath.

- In 1779, a skull of ichthyosaur was excavated from the quarries of Barrow-upon-Soar, Leicestershire.

- In 1804, Edward Donovan at St Donats (Wales) uncovered a four-metre-long (13 ft) ichthyosaur specimen containing a jaw, vertebrae, ribs, and a shoulder girdle. It was considered to be a giant lizard.

- In 1805, the "greatest part of a fossil Crocodile" was discovered by Reverend Peter Hawker of Woodchester in the country of

Gloucestershire at Weston near Bath, in a quarry about half a mile from the river Avon (not far away from Bristol).

According to the short description published by his cousin Joseph Hawker, who was a member of Geological Society, in 1807

in the Gentleman's Magazine (Volume 77, part 1), the fossil has a length over 3 meters (10.5 feet) "from the extreme part

of the head to the end of the tail". The specimen contained over 70 vertebrae. The head was about 1 meter long (3 feet 2 inches) and has

120 teeth.

This specimen gained some fame among geologists as 'Hawker's Crocodile'.

Later on, it was recognized as an Ichthyousaur, was studied and mentioned in several scientific articles.

("Additional facts respecting the fossil remains of an animal, on the subject of which two papers have been printed in the

Philosophical Transactions, showing that the bones of the sternum resemble those of the ornithorhynchus paradoxus.",

by Sir Everard Home in 1818.

"Some Account of the Order in which the Fossil Saurians were Discovered", by Cumberland G. in 1829).

It was housed in the Bristol Museum since 1823, until it was destroyed by bombing during World War II in 1940.

In 1814, Sir Everard Home, an anatomist for the Royal College of Surgeons described this fossil in an article

Some Account of the fossil remains of an animal more nearly allied to fishes than any of the other classes of animals

,

published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London.

This and five other papers he wrote, never mentioned who had collected the fossil,

and in the first paper he even mistakenly credited the painstaking cleaning and preparation of the fossil performed by Mary Anning

and her family to the staff at Bullock's museum.

Home’s article is the first scientific description of an ichthyosaur.

Home thought this animal formed a "connection between fish and crocodiles" in the Great Chain of Being and he declined to name it.

(The Great Chain of Being is a hierarchical structure of all matter and life, thought by medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God.

The chain begins with God and descends through angels, humans, animals, and plants, to minerals).

Almost all scientists at this time believed in the Divine creation of the Earth

and its life and had difficulties finding an explanation for the extinction of the animal.

It was a common belief at this time, that a God who created the world and all that was in it would not allow his

creations to disappear from existence.

All fossilized bones and tooth were assigned to either existing animals, crocodiles for example, animals dead

in the biblical (Noah) flood or to remains of biblical titans.

The fossil of the ichthyosaur found by the Annings was clearly from an unknown animal.

Scientists tried to assign the fossil to a living but yet undiscovered animal in order

to place it in the Great Chain of Being.

One such account was provided by the Reverend George Young in 1821.

In “Account of a singular fossil skeleton, discovered at Whitby in February 1819”,

which was published in the Wernerian Natural History Society Memoirs he wrote:

"It is not unlikely, however, that as the science of Natural History enlarges its bounds,

some animal of the same genus may be discovered in some parts of the world ...

and when the seas and large rivers of our globe shall have been more fully explored, many animals may be brought

to the knowledge of the naturalist, which at present are known only in the state of fossils."

On the other hand, other scientists tried to find reasonable explanations for the origin of these fossils.

One such explanation was provided by the French scientist, Georges Cuvier, who developed the theory that

extinctions could be caused by catastrophic events.

In his own words “to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.”

The name "Ichthyosaurus" appeared for the first time in 1817 in

the 12

th edition of "A Synopsis of the Contents of the British Museum" -

the booklet designed for self-guided tours of the Museum, as described in the introduction:

|

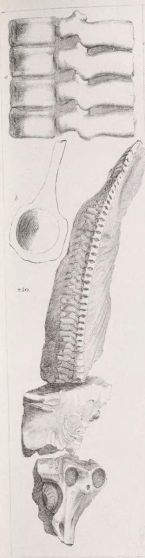

Above:

The fossil from collection of Natural History Museum im London. Specimen Nr.: BMNH R1122.

Image credit: NHMUK

Zoomed labels are here.

Image credit: Global Biodiversity Information Facility

Richard Lydekker in his "Catalogue of the fossil Reptilia and Amphibia in the British Museum (Natural history). Part 2", page 90,

published in London in 1889, provides a more

detailed description of this fossil:

"R. 1122. The imperfect cranium, and a mass of matrix containing a large portion of the vertebral column:

probably from the Lower Lias of Barrow-on-Soar, Leicestershire ...

The rostrum of the cranium is broken off immediately in advance of the nares;

the orbital region preserves its original contour, and the parietal foramen and

supratemporal fossae are entire.

The alveolar margins of the palate are imperfect.

Both the centra and arches of the vertebral column are preserved."

|

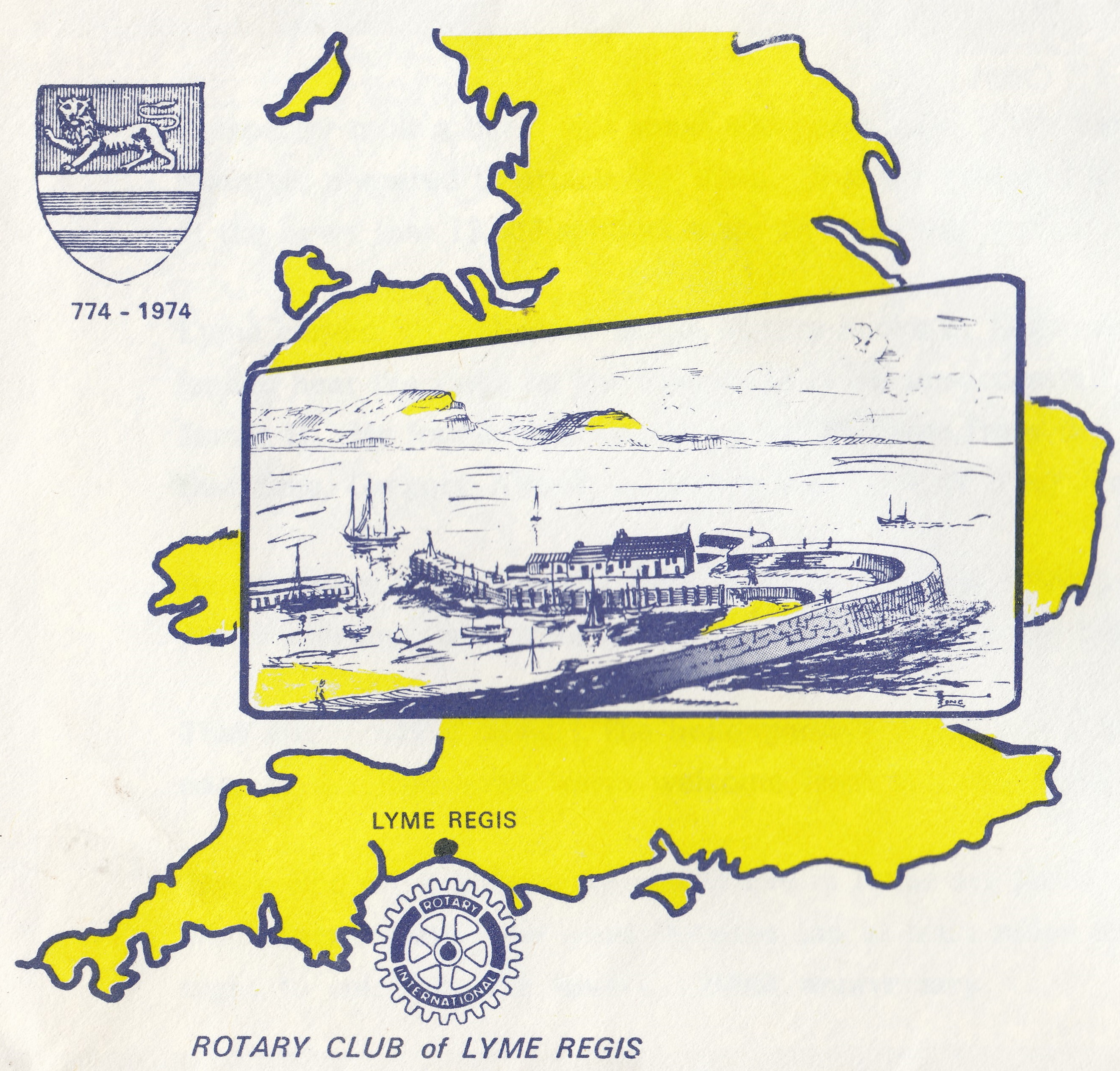

The "jaw and other bones of an animal" assigned by Koenig to "Ichthyosaurus".

Illustration Nr. 250, Plate XIX in "Icones fossilium sectiles", published by Koenig in 1825.

It seems as illustrator of Koenig straightened the vertebral column to better fit to

the plate.

|

The public is apprized that the following compendious Synopsis is merely intended for

Persons who take the usual cursory view of the Museum.

The following is a list of the more ample descriptions of several of the Collections

Below is an

extract from the booklet

(edition 13

th from 1817. The 12

th edition was published earlier in 1817):

"

NINTH ROOM.

In this room are deposited various petrifications, together with osseous and other fossil remains.

Among the latter the more remarkable are:

...osseous remains of a huge reptile of the natural order of lizards, being a genus intermediate between

the Monitor [old word of Varan] and Guana, from Maestricht in the Netherlands;-

jaw and other bones of the Ichthyosaurus, an animal apparently of the same natural order,

but referred to the fishes by Sir E. Home, from Dorsetshire.

..."

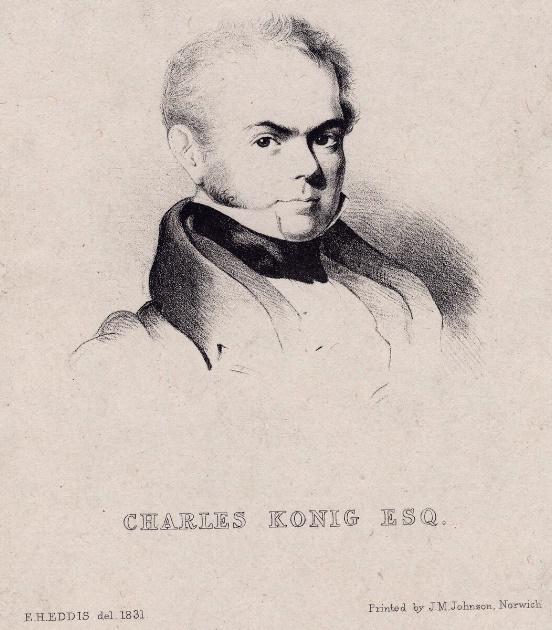

The name

Ichthyosaurus informally applied by curator of the Department of Natural History British Museum,

Charles Dietrich Eberhard Koenig (born Karl Dietrich Eberhard König in Germany).

He used this name, that means “fish lizard” in Greek because he realized that it has features of both fish and lizards.

(

Start from the 14th edition of the Synopsis,

the fossil description became more general, just an osseous remains, without any details.)

Origin of this fossil is unknown.

According to "Catalogue of the fossil Reptilia and Amphibia in the British Museum (Natural history). Part 2",

published in London in 1889, by Richard Lydekker it is probably from the Lower Lias of Barrow-on-Soar, Leicestershire.

Purchase or donation source marked as "No history" there.

Perhaps, it was purchased or donated to the British Museum in 1816 or 1817, as "... jaw and other bones of an animal apparently of the same natural order,

but referred to the fishes by Sir E. Home, from Dorsetshire." appeared in the Synopsis for the first time in the 11

th edition,

issued earlier in 1817.

By the way, the "osseous remains of a huge reptile of the natural order of lizards, being a genus intermediate between

the Monitor [old word of Varan] and Guana, from Maestricht in the Netherlands",

in previous editions of the Synopsys called more precisely "a large fossil jaw", belongs to a Mosasaur.

The fossil is shown in "Icones fossilium sectiles" of Koenig, on the

plate XII, image Nr. 140.

The Ichthyosaurus of Koenig assign to

Ichthyosaurus latifrons species by Richard Owen in 1840, and count as holotype today.

In "Report on British Fossil Reptiles", published in the Ninth Meeting Report of the British Association for the

Advancement of Science (London, 1840), Richard Owen described it:

"

Ichthyosaurus latifrons, Koenig. (Icones Sectiles, pi. xix.)

This species is founded on a specimen in the British Museum,

including a portion of the cranium, of which the anatomy

is admirably worked out, and part of the vertebral column.

Besides the character expressed in the specific name proposed

by the accomplished Mineralogist and Palaeontologist, whose

name is associated with the genus, of which the present species

forms so interesting an addition; the foramen parietale appears

to be unusually large ; and the articular surfaces of the bodies

of the vertebrae present a flattened circumference."

Koenig did not publish the name until 1825 (in the Icones fossilium sectiles).

Other scientists adapted the name ichthyosaur in their publications – which fixed the term in the paleontological literature.

Since 1814 when Everard Home examined and described

"the fossil remains of an animal more nearly allied to fishes than any of the other classes of animals",

he was intrigued by the strange animal and tried to locate additional specimens in existing collections.

On March 4th 1819 Home read his paper "An Account of the Fossil Skeleton of the Proteo-Saurus" in

a meeting of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, published by the Society in the same year.

"In the year 1814, the skull and vertebrae of this fossil skeleton were first described in

the Philosophical Transactions; and so much was the attention of the public called to the

subject by that account, and so many specimens were brought under my observation,

that in the year 1816, I was enabled to make many valuable additions."

In this paper Home argues that based on many other fossils of the same animal,

he changed his mind about the relationships of the animal

and came to the conclusion it is an intermediate form between salamanders and lizards.

The fossil from collection of Colonel Birch (1768-1829), acquired

at Lyme Regis by September 1818 anad named by Everard Home as Proteo-Saurus in 1819.

The fossil from collection of Colonel Birch (1768-1829), acquired

at Lyme Regis by September 1818 anad named by Everard Home as Proteo-Saurus in 1819.

The drawing made by William Clift for paper of Everard Home.

Image credit: the British Museum

|

Many fossls of marine prehistoric animals, includes Ammonites, can be found in Lyme Regis.

|

|

One of these specimens was the nearly complete skeleton from collection of Colonel Birch,

who was spending his half-pay pension touring the West Country collecting fossils and who acquired it

(probably from Mary Anning) at Lyme Regis by September 1818, that showed the hind limbs

(means the animal was definitely not a fish), but had fish-like vertebrae.

As Home identify some similarities between these vertebrae and those of the salamander

Proteus,

he propose naming it

Proteosaurus.

(

Proteosaurus was referred to the large ichthyosaur now called

Temnodontosaurus platyodon).

As the name Proteosaurus was published first, it actually has precedence over the name ichthyosaurus,

but was rarely used and soon forgotten.

Ichthyosaurus was likely preferred because people thought the term ichthyosaur (fish lizard) fit better than Proteosaurus.

Although Proteosaurus should be used today by the present standards of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature,

which was not available yet at the time of Home, most naturalist rejected it and continued to use Ichthyosaurus name.

Ironically, Home's interpretation was closer to recent interpretation of Ichthyosaurus

relationships, then had been proposed by Koenig.

In the paper read to the Geological Society in 1819, but not published until 1822, Henry De la Beche named

three species of Ichthyosaurus, which he distinguished with skull and tooth characters:

the smaller and most common

Ichthyosaurus communis,

longer-snouted

Ichthyosaurus platyodon and

flatter-toothed

Ichthyosaurus tenuirostris.

In 1821, in the first comprehensive description of ichthyosaur anatomy, De la Beche and Conybeare

used Koenig’s

Ichthyosaurus, stating that the animal’s analogies with

Proteus were insufficient

to sanction the changing of the earlier name.

In their paper, "Notice of the discovery of a new Fossil Animal, forming a

link between the Ichthyosaurus and Crocodile, together with general

remarks on the Osteology of the Ichthyosaurus" from 1821, they explain their decision:

"We have retained in these observations the name Ichthyosaurus, originally applied to this animal by Mr. Koenig of the British

Museum, feeling convinced that on a full and careful review of its whole structure, it will not be found to possess analogies sufficiently

numerous or strong with the peculiar organisation of the Proteus to authorise the change of this appellation

into Proteosaurus, as subsequently proposed."

In this paper, De la Beche & Conybeare presented a synthesis from many specimens, and attempted a reconstruction of the head

and named the species

Ichthyosaurus communis based on a now lost specimen.

In the same paper they also provided the first systematic description of ichthyosaurs, comparing them to another newly identified marine reptile group, the Plesiosauria.

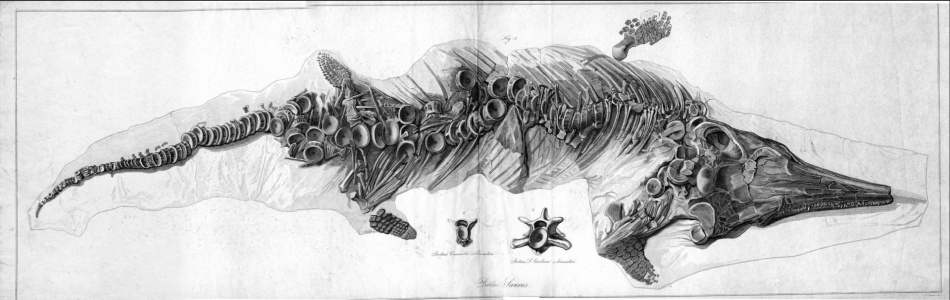

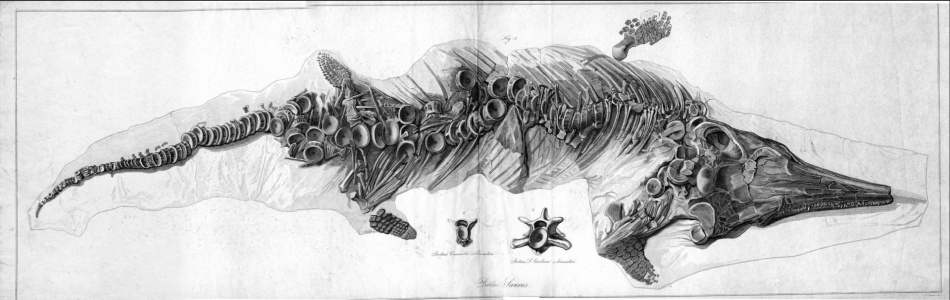

Later reconstruction of Ichthyosaurus communis by William Conybeare from his article

"On the Discovery of an almost perfect Skeleton of the Plesiosaurus".

Transactions of the Geological Society of London, S2-1 (1824).

Later reconstruction of Ichthyosaurus communis by William Conybeare from his article

"On the Discovery of an almost perfect Skeleton of the Plesiosaurus".

Transactions of the Geological Society of London, S2-1 (1824).

The skeleton was based primarily on a [now lost] fossil specimen found by Mary Anning which

was purchased by subscription for £50 and presented to the Bristol Institution by a number of its members (including Conybeare) on 4 January 1823.

Image credit: the Geological Society of London.

The very first reconstruction of an Ichthyosaur was done by the English geologist Henry De la Beche in 1830,

who painted it as a mix of fish and crocodile in his painting, “Duria Antiquior”,

which is the very first painting to show prehistoric life as the painter interpreted them.

"Duria Antiquior",

a more ancient Dorset in English,

based on evidence from fossil reconstructions, a genre now known as paleoart,

based on fossils found at Lyme Regis, Dorset, mostly by the professional fossil collector Mary Anning.

De la Beche had hired the professional artist Georg Scharf to produce lithographic prints based on the painting,

which he sold to friends to raise money for Anning's benefit.

The print was used for educational purposes and widely circulated in scientific circles;

it influenced several other such depictions that began to appear in both scientific and popular literature.

Several later versions were produced by De la Beche in the coming years.

[R5]

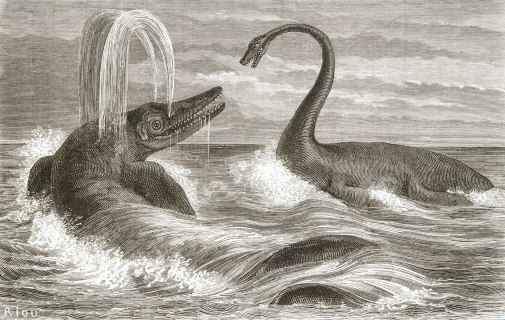

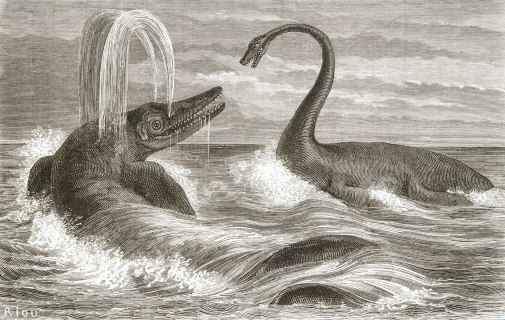

Crocodile-like representation of Ichthyosaurs survived for a long time in art and in the scientific

literature, as can be seen on the painting of Édouard Riou from 1863, who painted it fighting with a Plesiosaur.

This was painting also used as one of the illustrations in Jules Vernes’s Journey to the Center of the Earth.

|

|

|

Duria Antiquior - the first representation of a scene of prehistoric life.

Image credit: Wikipedia

|

Ichthyosaur and Plesiosaur by Édouard Riou, 1863.

Image credit: Wikipedia

|

According to recent research on plesiosaurs, such lifting of it is head (swan-like), as shown in the drawing is absolutely impossible.

Contrary to earlier depictions, plesiosaurs necks were not very flexible, and could not be held high above the water surface.

The necks of plesiosaurs were fully unlike those of animals with really flexible necks like many birds for example.

The vertebrae were rather short and there was very little space between the centers of the vertebrae.

Their dorsal spines were very long and broad, which reduced the amount of possible vertical movement a lot.

Unlike those of many other long-necked animals, the individual neck vertebrae on plesiosaurs were not particularly elongated; rather,

the extreme neck length was achieved by a much increased number of vertebrae.

Elasmosaurus, a genus of plesiosaur, had extremely long necks that could be over 7 meters in length

(60% of the entire length of the animal!).

They differed from other plesiosaurs by having 72 neck or cervical vertebrae.

The weight of its long neck placed the center of gravity behind the front flippers.

Thus, Elasmosaurus could have raised its head and neck above the water only when in shallow water, where it could rest its body on the bottom.

The weight of the neck, the limited musculature, and the limited movement between the vertebrae would have

prevented Elasmosaurus from raising its head and neck very high.

[R11]

Some single bones and even parts of Ichthyosaur skeletons were found in the mainland of Europe too, especially in the in the Posidonia Shale,

even before the famous find of Mary Anning, but all assigned to fishes or left unclassified at all.

The Posidonia Shale

(German: Posidonienschiefer, also called Sachrang Formation, Schwarzerschiefer,

Lias-Epsilon-Schiefer, Bächental-Schichten and Ölschiefer Formation)

is an Early Jurassic (Toarcian) geological formation of southwestern Germany,

northern Switzerland, northwestern Austria, southeast Luxembourg and the Netherlands,

hosting exceptionally well-preserved complete skeletons of fossil marine fish and reptiles.

The Posidonienschiefer, as German paleontologists call it, takes its name from the ubiquitous

fossils of the oyster-related bivalve Posidonia bronni that characterize the mollusk

faunal component of the formation. [R4]

One such place is the region in South-West of Germany - to the South of Stuttgart.

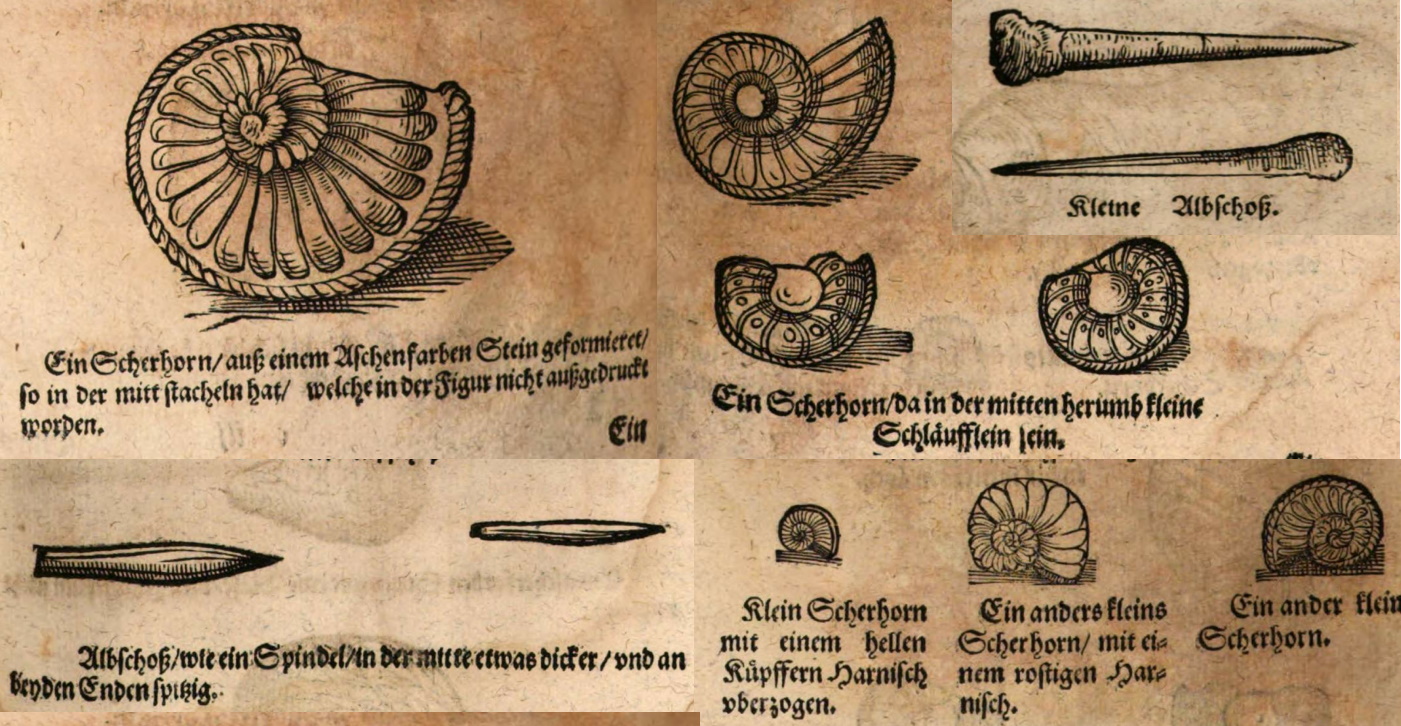

The very first documented fossils recorded from this region date to 1602.

At the end of XVII century German Aristocrats discovered the power of warm, mineral water

sources of this region and built some resorts there.

At Bad Boll German Duke Friedrich I. von Wuerttemberg constructed a resort (Kurhaus in German) around 1596.

The Duke approached his personal medical assistant, Johannes Bauhinus to explore the region.

Later, in 1602, Bauhinus published a book

„Ein neues Badbuch und historische Beschreibung von der wundersamen Kraft und Wirkung des Wunderbrunnen und heilsamen Bads zu Boll"

(in English: “A new Resort book and historical description of the miraculous power and effect of the miracle fountain and healing Bad Boll"),

also known as just "BadBuch".

As was common at the time, the book covered a wide variety of topics about the region including history,

culture and traditions of local folk, plants of the region, as well as other “wonderful things” like fossils and minerals.

Most of the fossils include Ammonites, bivalve and belemnites, called Albschoss - the old German word for shells of prehistoric animals.

One such “Albschoss”, depicted on page 751, described as

„

Ascherfarben Albschoß/wie ein Hundezahn/mit dreifachem Furchen durchzogen“

or “

Ash-colored Albschoss / like a dog tooth / with triple furrows” in English.

This “tooth” is very likely the tooth of a marine reptile, but it is impossible to assign it to any known species without

reexamining the fossil.

Unfortunately, the specimen illustrated has been lost in the intervening years.

It is possible that this could be the tooth of an ichthyosaur or possibly of a crocodile-like reptile

Steneosaurus

found in the area.

Many fossils of these animals were discovered in the region in the XX

st and XXI

st centuries.

[R7]

The author communicated with several experts to try to find out more about this illustration.

Here are their opinions:

-

“To the best of my knowledge, the object is not in our collections.

Based on the illustration, the tooth crown seems to be too tall, slender, and recurved to belong to Temnodontosaurus trigonodon (the only ichthyosaur from the region with carinate teeth);

in my opinion a referral to Steneosaurus (thalattosuchian crocodile) is more likely.

However, given the style of illustrations during the time period, it's probably more realistic to consider the find to be the indeterminate tooth of a marine reptile.”

Dr. Erin Maxwell, the curator for fossil aquatic vertebrates

at the Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History.

-

“If the illustration is accurate, there are a few reasons to believe that this is not an ichthyosaur tooth (and may not even be a tooth).

I have never seen an ichthyosaur tooth with a prominent furrow like that (and it is said there are three of them).

Also, Jurassic ichthyosaur teeth are not open near the bottom as figured--the pulp cavity is minimal in size at the bottom of a tooth.

It may be possible that the bottom half of the tooth, i.e., the root, is gone and only the crown is left; however, even in that case, the opening is far too large for an ichthyosaur tooth.

Also, if that concentric pattern that is figured near the right end is really there, that kind of structure can only be made by a germ tooth eating into the root of its predecessor

(i.e., the tooth figured would be the predecessor).

If that is the case, the root is preserved to the bottom of the root.

I am not as familiar with Thalattosuchian teeth but I doubt that deep furrows and such a wide opening are there in these animals either (you probably want to check with a specialist).

I have a strong suspicion that it may be an invertebrate.”

Ryosuke Motani, Ph.D., Professor Dept. Earth and Planetary Sciences University of California

-

"From what I can see from this somewhat crude illustration, I would hesitate to make a definitive identification as to what animal it represented.

While it bears a superficial resemblance to an ichthyosaur tooth with its curved conical shape, the "shading" lines show a distinct grooving along

the concave side which I've not seen in ichthyosaurs."

Dr. Chris McGowan, retired paleontologist who worked at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada.

His main research interests are vertebrate paleontology and the paleobiology of the Mesozoic Era.

Dr. Mcgowan is an author of many articles about ichthyosaurs.

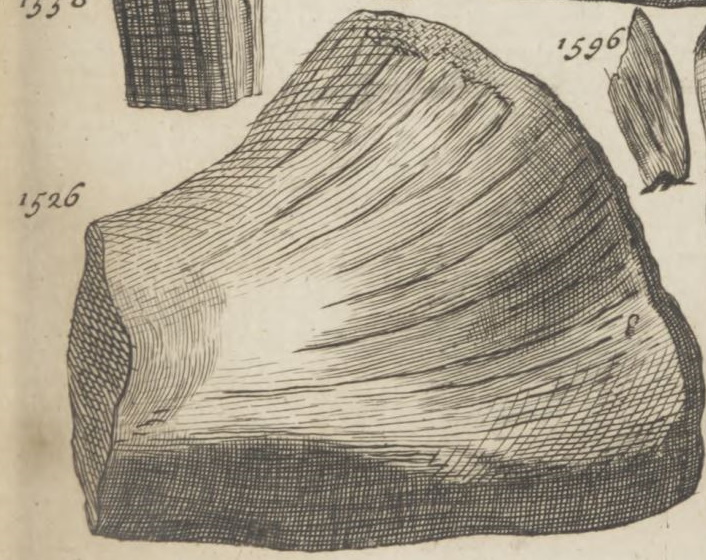

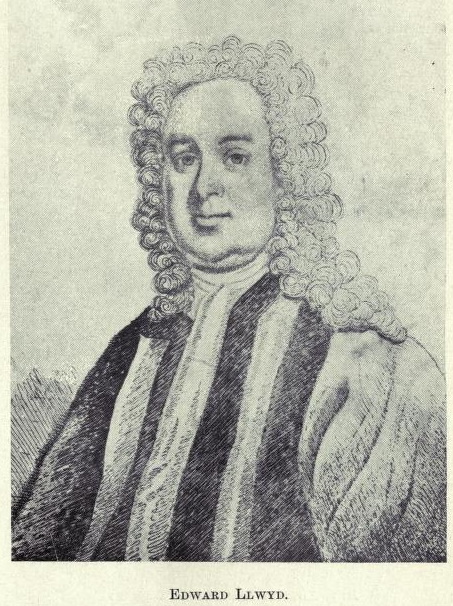

The first confirmed illustration of ichthyosaur fossils appeared in 1699 when

a Welshman Edward Lhuyd (in welsh standard orthography: Llwyd), who was the second keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, published

an illustrated catalog of the museum "

Lithophylacii Britannici Ichonographia”,

in English "

British Figured Stone" (the first book devoted solely tp British fossiils).

Lhwyd’s had very interesting views on the origin of fossils.

“He suggested a sequence in which mists and vapours over the sea were impregnated with the

‘seed’ of marine animals.

These were raised and carried for considerable distances before they descended over land in rain and fog.

The ‘invisible animacula’ then penetrated deep into the earth and there germinated; and in this way

complete replicas of sea organisms, or sometimes only parts of individuals, were reproduced in stone.

Lhwyd also suggests that fossil plants known to him only as resembling leaves of ferns

and mosses which have minute ‘seed’, were formed in the same manner.

He claimed that this theory explained a number of features about fossils in a satisfactory manner:

the presence in England of nautiluses and exotic shells which were no longer found in neighboring seas;

the absence of birds and viviparous animals not found by Lhwyd as fossils; the varying and often

quite large size of the forms, not usual in present oceans; and the variation in preservation from

perfect replica to vague representation, which was thought to represent degeneration with time”

(Edmonds, 1973, p. 307-8)

This book, printed in 120 copies and sold for privately subscribers only,

consisted of a catalogue of 1,766 minerals and fossils, and was the first

illustrated catalogue of a public collection of fossils to be published in England.

It contained images of three ichthyosaur vertebrae from the Lower Jurassic Lower Lias

(earliest part of the Jurassic, from about 205 to 180 million wars ago)

of Pyrton Passage, Gloucestershire.

|

|

|

|

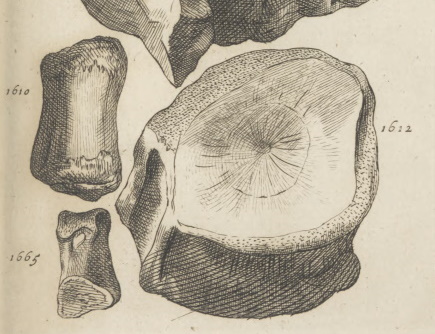

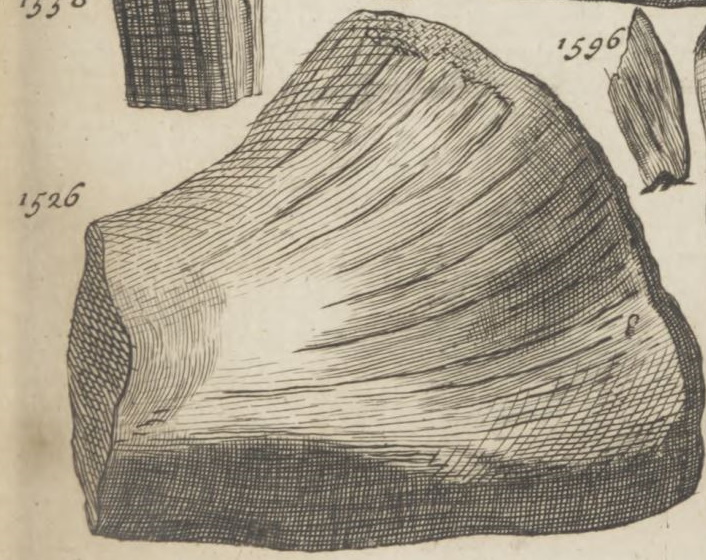

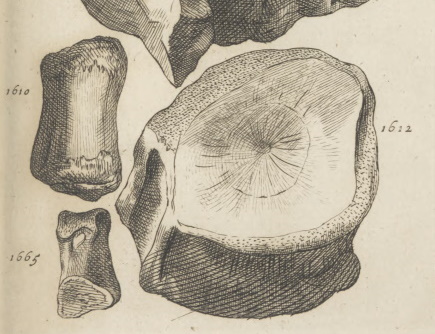

Various Ichthyosaur vertebrates figured in a book written by Edward Lhuyd, published in 1699.

All three collected at the Lower Jurassic Lower Lias [R6] of Pyrton Passage, Gloucestershire.

The images are from the reprint edition by Editio Alterata, 1760. Plates 17-19.

|

Nr. 1526 - scapula (shoulder bone),

Nr. 1528 - humerus (a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow),

Nr. 1612 - centrum (spinal column).

All these bones have been mistakenly identified as belonging to fish and called

Ichtbyospondyli.

Other vertebrae of other prehistoric animals are shown in the book have been identified as the vertebrae

of Plesiosaurs and prehistoric Crocodiles which have also been found in the same region.

|

|

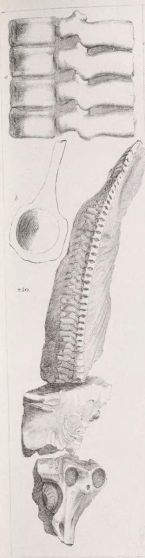

|

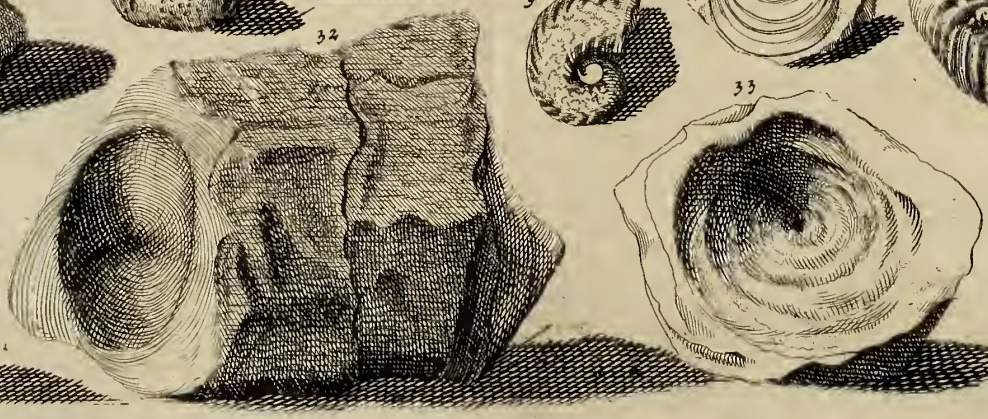

Ichthyosaur vertebrae from book of Johann Jakob Scheuchzer, published in 1708.

|

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672-1733) on commemorative postmark of Switzerland 1977.

|

|

|

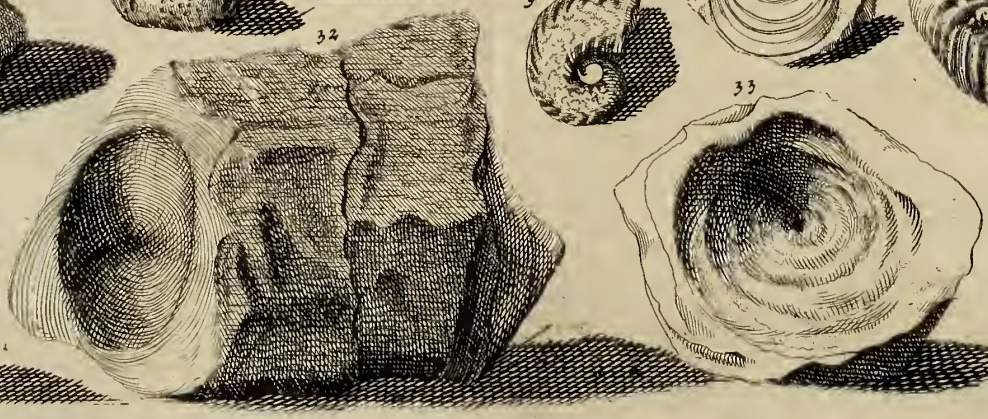

Ichthyosaur vertebrae (Nr. 32, 33) from book of Johann Jakob Baier, published in 1708.

|

In 1708 Swiss scholar, Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672-1733), who also known as one of the founder of paleobotany,

published a book in Latin "

Piscium Querelae Et Vindiciae".

One of the illustrations shows two ichthyosaur's vertebrae (backbone) that he found in 1692 near gallows hill by Altdorf,

near Nuremberg, in Bavaria (now Germany), where he went to the University, being intended for the medical profession.

One day, Johann Scheuchzer was with a fellow student on a Gallows Hill, in Altdorf,

when the fellow found a piece of rock with eight articulated vertebrae.

In panic, assuming the vertebrae to be those of a hanged man, he threw the rock fragment

containing them down the hill in disgust.

Schechzer, however, retrieved two of the vertebrae for his fossil collection.

Scheuchzer described this vertebra as a remnant (leg bone) of a human who drowned during the biblical flood.

The same year German naturalist, Johann Jakob Baier who was a professor of medicine at the University of Altdorf

and doctor in Nuremberg, published a book in Latin that bore the difficult name

"

Oryctographia norica sive rerum fossilium et ad minerale regnum pertinentium interritorio

norimbergensis eijusque vicinia observatarum succinita descriptio”,

in English: "

Brief description of the fossils and minerals of the

territory of Nuremberg and its neighborhood”.

One of the illustrations shows two other vertebrae of ichthyosaur found in Altdorf.

In opposition to Scheuchzer, Baier did not believe that it was a remnant of a human.

He assigned it to a marine animal and explained that the marine animal was swept out

of the ocean onto land.

In the coming years Baier and Scheuchzer exchanged several letters in Latin and German

where they discussed the origin of these vertebrae.

The first complete skeleton of an ichthyosaur, with head, neck and a tail was found in England in 1821 by the famous Mary Anning.

Next year, in 1822, Willian D. Conybeare, who examined and described the skeleton discovered by Mary Anning,

assigned ichthyosaurs to reptiles and assigned the skeleton to the species

Ichthyosaurus communis,

that would later come to be known as

Leptonectes tenuirostris.

In his article "

Additional Notices on the Fossil Genera Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus" he explain:

"... I had originally, it will be remembered, compared it principally to the crocodile;

and after a very mature examination, I am still of opinion that the analogies between the

Ichthyosaurus and that family are more striking and numerous, than those which connect it

with the other tribes of Lacertae. ..."

|

|

Specimen of the ichthyosaur Stenopterygius

(an almost complete skeleton save for the head and neck that died giving birth to a new-born)

collected in 1749 from a quarry near Bad Boll by Albert von Mohr.

Image credit: Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart

|

In autumn 1822, German paleontologist Georg Friedrich von Jaeger visited

the Royal high school in Stuttgart (in German: Königliche Gymnasium zu Stuttgart).

Von Jaeger examined their fossil collection, where he found the Bad Boll specimen

collected by Dr. Albert Mor in Bad Boll (30km south of Stuttgart) in 1749.

The Bad Boll specimen consisted of the torso and tail.

The specimen also had an embryo.

Mor had assigned it to the ray-like fish and essentially ignored the specimen from then on.

Jaeger, who was familiar with publications of Willian D. Conybeare, Sir Everard Home, Charles Koenig and Baron Georges Cuvier,

recognized it as a partial skeleton of an ichthyosaur.

Nowadays, this fossil, which is the oldest discovered Ichthyosaurus skeleton, is in collection of

Natural History Museum in Stuttgart and assigned to the genus Stenopterygius, who lived during the Early Jurassic.

Jaeger published his observations in Latin, "

De Ichthyosauri sive Pro-

teosauri fossilis Speciminibus in agro Bollensi repertis" in 1824 and in 1828 in German

"

Die fossile Reptilien, welche in Würtemberg aufgefunden worden sind".

In his monographs, he provided a very detailed description of the fossil, as well as several other prehistoric

reptiles discovered near Stuttgart, but made no note or explanation for the baby ichthyosaur.

His brief description was that there both a big and small individual laid together.

However, in his lecture at the meeting of German naturalists and doctors in Mainz, that took place on November 20

th 1842,

Jaeger gave a notice of the possibility that the small animal is a baby of the larger individual.

He is recorded as having suggested ichthyosaur viviparity.

(Viviparous animals give live birth.)

Recent research suggests that Jurassic ichthyosaurs birthed their young tail first.

Perhaps the Bad Boll specimen, with the baby coming out with snout first,

instead represents a mother that had died from other circumstances and after death,

the fetus was rotated and pushed out by decomposition gases.

The first written document about reproductive strategy (viviparity) of these aquatic reptiles

was written by Joseph Chaning Pearce in 1846, based on the fossil he found

from the rock in the brown laminated Lias clay of Somersetshire.

Pearce’s specimen is now in the collection of the Natural History Museum in London.

|

|

Ichthyosaur fossil with the tiny embryo (marked on the rock), collected and described by Joseph Chaning Pearce.

Image of the complete skeleton is here (the one on the bottom).

Image credit: Dr. Dean Lomax

Note: the author added the red marker to highlight the position of the embryo.

|

Pearce collected fossils since he was only 5 years old.

At the time of his death (at age 36), his fossil collection contained over 5000 specimens.

De la Beche described it as "one of the finest private collections of organic remains in this country".

In his article

"

Notice of what appears to be the Embryo of an Ichthyosaurus in the Pelvic cavity of Ichthyosaurus (communis?)",

he described his observations:

"...when we consider that the large animal war developed on its under surface consequently

it is nothing that has fallen upon it and the remarkably correct position of the little

skeleton in the pelvis, between the right and left ribs, with its head protruding

and the little vertebrae so exactly corresponding in shape to the large ones,

and the other bones resembling those of a Saurian, it appears fair to conclude that it

cannot be anything else but a foetal Ichthyosaurus ;

and if it be suggested that it may have been swallowed by the animal, this involves

a much greater difficulty; for so delicate a structure would have been dissolved by

the gastric juice, and could not have reached its present position.

The Rev. Dr. Buckland and Professor Owen, who have kindly written me on the subject, state,

that there is no reason why the Ichthyosaurus should not be viviparous, ..."

The argument, however, for cannibalism rather than embryos continued to persist.

[R3]

In 1908, German naturalist Wilhelm von Branca published an article

"

Nachtrag zur Embryonenfrage bei Ichthyosaurus"

(in English: "

Addendum to the embryo question of Ichthyosaurs")

where he argues his theory about ichthyosaur's cannibalism.

His arguments are:

- some adults contain juvenile skeletons of various sizes

- some juvenile lie close to remnants of chewed food

- most skeletons face the same direction as the adult (Branca considered tail-first birth style as unlikely)

- most juveniles skeletons lie away from the region of the uterus

- ribcages commonly contain up to 10 or 11 skeletons (Branca argued that whales and dolphins usually give a birth to a single large calf,

therefore many small juveniles skeletons between ribcages of an adult animal should be another argument to support his theory)

In 1989, German paleontologist Ronal Boettcher published his study of more than 40 skeletons of

Stenopterygius with young found in the south German Posidonia Shales (Lower Jurassic).

In his article "

Neue Erkenntnisse ueber die Fortpflanzungsbiologie der Ichthyosaurier"

(in English: "

New information on the reproductive biology of ichthyosaurs")

he explained that it is very unlikely that

Stenopterygius preyed on young ichthyosaurs.

His arguments (commonly accepted today by most paleontologists) are:

- juvenile skeletons of various sizes can be embryos at different stages of development

(as known in some more modern viviparous reptiles) or perhaps some of the juveniles were stillborn

(some modern animals abort their dead embryos only after the birth of the surviving offspring).

- most of the juvenile skeletons were found too far away from the stomach region of the adult animal

- the embryos have their snouts pointing towards the front of the mother – which suggests that they were born tail-first.

This birth style is not uncommon in modern aquatic animals, such as dolphins or whales.

It likely is an adaptation for air-breathing animals confined to water, allowing the young to quickly swim

to the sea surface to breath after birth.

- swallowed animals would lie disordered in the ribcages of the adult animal, but there are many specimens where

juveniles lie parallel each to other.

- the bones of juvenile are not etched by stomach acid and show no sign of predation like bite marks.

- Ichthyosaur stomachs seem to have been too small to contain so many juvenile prey at one time.

Juvenile skeletons are 50 cm to 85 cm in length and paleontologists think that these would be too large

to be contained in the stomach of Stenopterygius - especially when there were up to 11 juveniles.

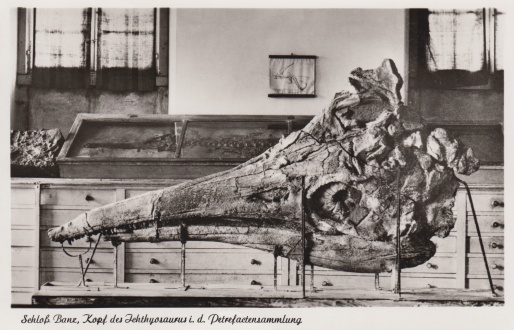

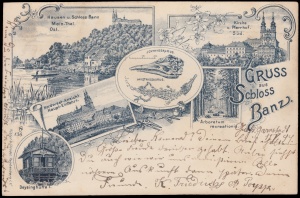

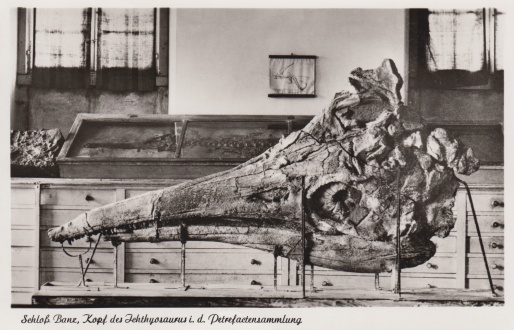

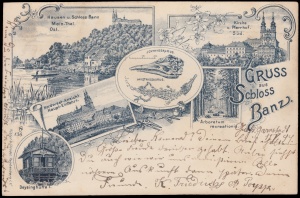

In November 1841, some construction to strengthen the river bank took place by Unnersdorf near Bad Staffelstein, 2km away from Banz Monastery,

about 34km northern of Bamberg in Bavaria (now part of Germany).

During the extraction of stone from the nearest hill, a 2.1 meter long ichthyosaur skull

(largest Ichthyosaur skull discovered in Europe to date) and a partial, disarticulated skeleton were found.

[R8]

|

|

The skull of ichthyosaur (Ichthyosaurus trigonodon) as well as fossils of

prehistoric crocodile Mystriosarus and Pterodactyl

from collection of Banz Monastery, depicted on a landscape

postcards "Greeting from the Banz Castle".

|

Excavation of these fossils were made under very difficult circumstances - bad and cold weather as well as

the need to ablate large amount of rock.

The skull was so big and heavy that almost all of the men of the community of Unnersdorf were mobilized to extract

and transport it over the hills to the fossil collection (Petrefakten Sammlung) of the Monastery.

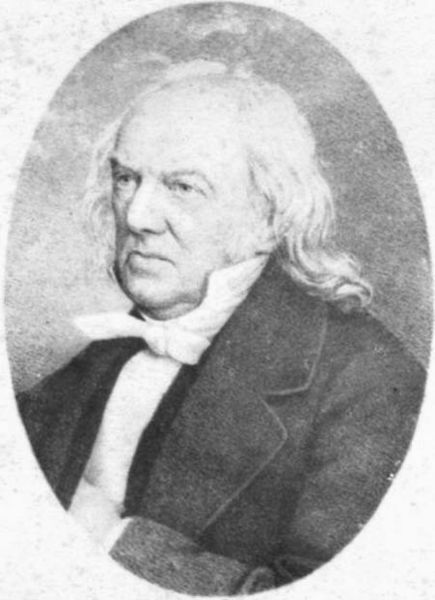

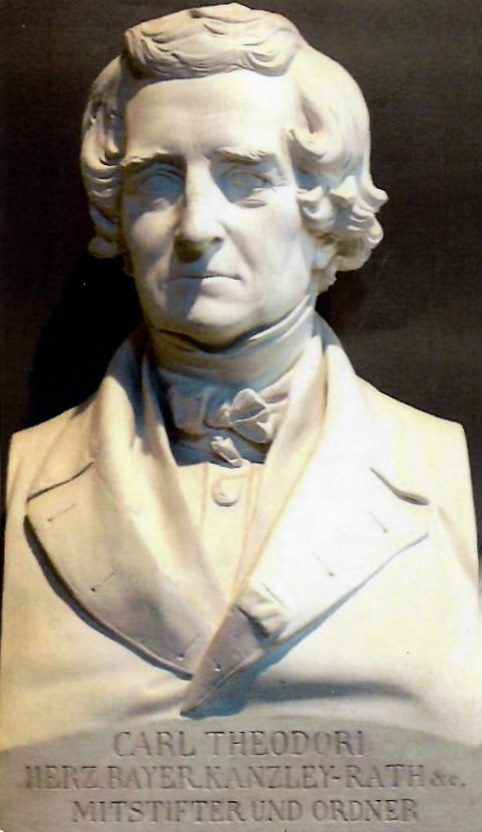

These fossils were described by German lawyer, artist and naturalist Carl von Theodori (1788 - 1857),

who published a short notice in "Gelehrte Anzeigen" (Scholarly Report)

on June 8

th 1843.

In this short article (three pages), Theodori compared the ichthyosaur from Banz with some other ichthyosaur genera

known at that time.

He found that the closest species is

Ichthyosaurus platyodon (CONYBEARE, 1822),

as it has some similar features, the skull for example,

but their teeth have a different form - flat in

Ichthyosaurus platyodon, but triangular in cross-section

in the one from Banz, therefore he decided to call it

Ichthyosaurus trigonodon.

Later on, both species were reassigned to Temnodontosaurus platyodon and Temnodontosaurus trigonodon accordently.

Nowadays, some paleontologists propose that Temnodontosaurus trigonodon is a junior form of Temnodontosaurus platyodon.

The Banz ichthyosaur skull is on display in the fossil collection of the Banz Monastery (Kloster) today.

Estimated length of the animal is 9-11 meters.

The historical fossil collection (originally called Petrefaktensammlung in German) is one of the oldest

paleontological exhibits in Bavaria and was created in 1828 by Carl von Theodori

and the Catholic clergyman and fossil collector Augustin Geyer (1774 - 1837).

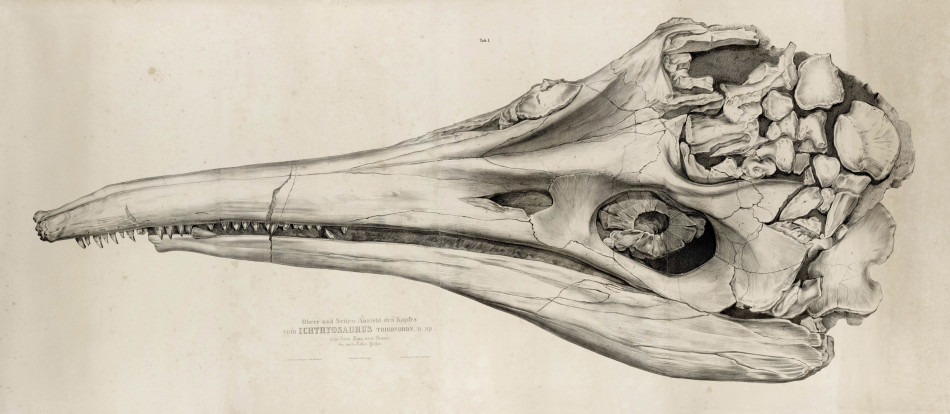

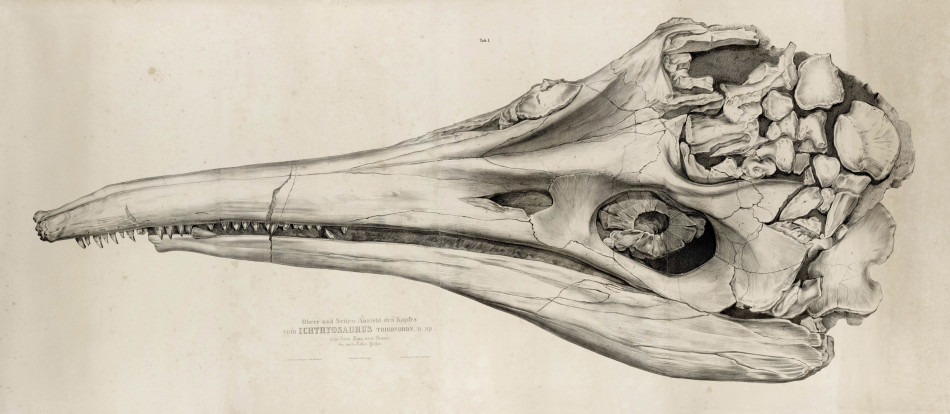

In 1854 Carl Theodori published a very detailed article that contains over 100 pages -

"Beschreibung des kolossalen

Ichthyosaurus trigonodon in der Lokal-Petrefakten-Sammlung zu Banz nebst synoptischer

Darstellung der übrigen Ichthyosaurus-Arten in derselben. Mit Abbildungen in natürlicher Größe".

In English

"Description of the Colossal

Ichthyosaurus trigonodon from the local

fossil collection at Banz along with synoptic representation, with illustrations in natural size".

The drawing of the Ichthyosaur skull attached to the article was drawn in the same scale as the

original fossil, to allow the readers to examine it's very fine details.

In this article Theodori has not only a detailed description of this fossil and sediments where it was discovered,

but also tells the story of the discovery and provide his explanation how it came there.

A translation of “About the Discovery of the

Ichthyosaurus trigonodon” a section within the article on pages XIII-XIV is below.

The original title in German is “Ueber die Auffindung des Ichthyosaurus trigonodon".

Note: the images were added by the author of this article.

"About the finding of the Ichthyosaurus trigonodon

[R8d]

|

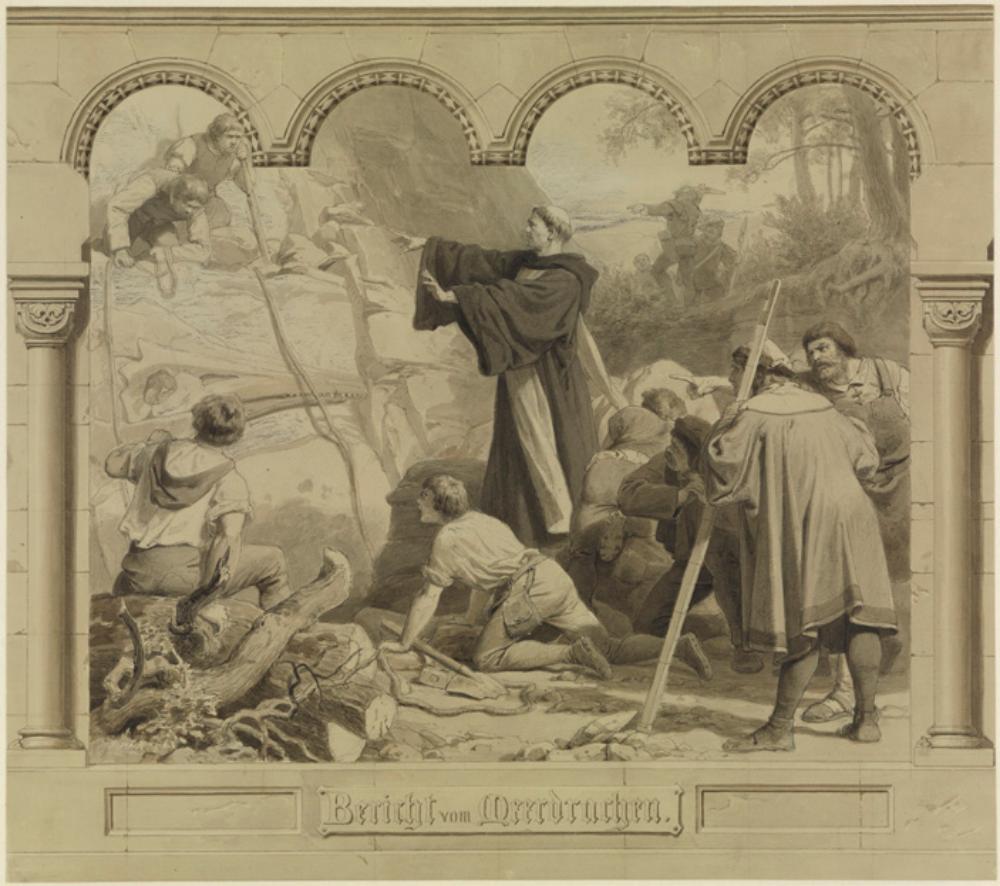

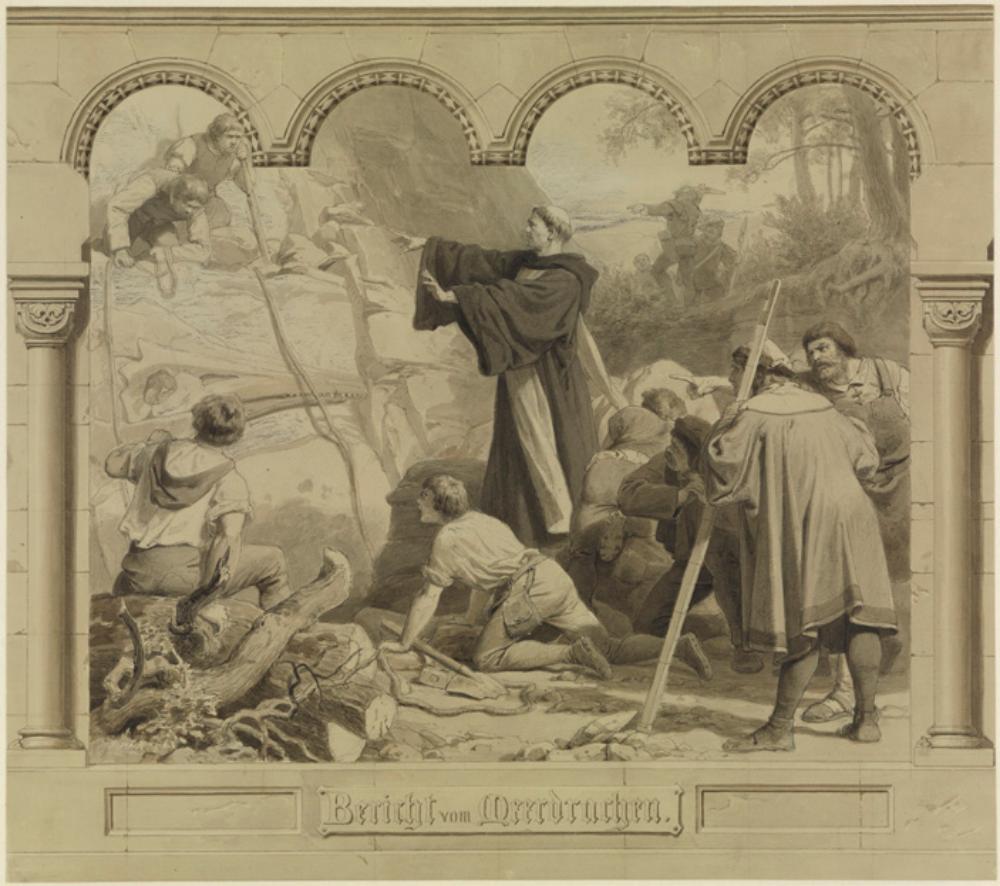

"Report from the sea dragon", in German "Bericht vom Meerdrachen", by Anton von Werner, painted in 1863-1864.

This painting illustrates the discovery of the Ichthyosaur, based on "Frau Aventiure" verse of

Joseph Victor von Scheffel, published in 1859.

Image credit:

Staatliches Kunsthalle Karlsruhe

|

A short distance upstream from the bridge crossing the Main River near the village of Unnersdorf

on the right bank are exposed impressive rock formations at the foot of the mountain crowned by Banz Castle.

They consist of bituminous Upper-Lias marls and limestones.

Rocks from these outcrops were quarried for a riverbank construction in 1842

[in his article from 1843, Theodori mentioned November 1841 as the date of the discovery].

A rather strongly weathered colossal lower limb bone of an Ichthyosaur was found during this activity and shown to the then priest

at Banz, H. Murk, an avid collector for the Herzogliche Lokal-Petrefakten Kabinet (the fossil collection of the local duke).

He advised to follow the clue left by this find.

To this end more than 12 meter of overburden had to be removed till, 28-29 meter above the present level of the Main,

the geological layer that had contained the upper limb was reached.

The remains of the skeleton belonging to the earlier bone were found, spread over an area of 3,5 meter.

This provided also the proof that the largest part of the torso with the hind limbs was torn away by the floods, that,

in olden days, eroded the Main valley.

It was for this reason, that the exposed bones went from the slope of the valley

wall into the mountain and ended with the colossal head.

The excavation of this large conglomeration of bones took place under very difficult circumstances, but, thank goodness,

the head is now fully freed from the sediments that enclosed it and is displayed, supported by strong iron brackets,

in the largest hall of the collection.

The bones belonging to the skeleton are spread on individually recovered slate slabs with the body outline shown.

They are enclosed in a box and assembled to an exhibit of 2,33 meter width and 4 meter length.

|

|

|

The skull of the ichthyosaur in the fossil collection of Banz Monastery.

The photo on the left was taken in the early 1900s and has appeared on some

postcards.

The photo on the right is a modern image of the same specimen from

redaktion42.com.

|

I would like to add some thoughts here.

These skeleton remains have been found in a basin of the Keuper [R6] embedded in Lias [R6], showing a forceful contact of the animal with a solid object.

The front part of the lower jawbone, thick like a beam, is broken off.

The tip of the upper jaw is bent; the back of the head is bashed in by a counter impact; the cervical vertebrae are pushed on top

of each other and the anterior ribs are bent in an acute angle.

All that could only have happened by bouncing the head, reinforced by a tremendous thrust from the body.

Thus, it can be assumed that the stranded animal has been hurled by the floods with great force against the wall of the Keuper shores.

Its remains, however, were not found in the immediate vicinity of the wall of the Keuper basin but quite a distance from the same, buried in the Lias.

But what stands in the way to assume that the carcass was not carried away from the shore by subsequent floods?

The carcass decomposed and the skeleton was probably for some length of time in the water, because there are, without doubt, signs of a corrosive nature on several bones.

The skeleton disintegrated finally and the floods played with the remains so that they individually or as connected parts came to rest in the sediments

which preserved and kept them for the research of later generations.

The details listed so far can only be explained by external, random and violent forces in a horizontal direction; but the crushing of the

skeletal parts and especially of the head cavities in a vertical direction will appear equally natural when one considers the enormous

pressure exercised by the thick sediments of the Upper Lias Formation on the layer that preserved the remains of our Ichtyosaurus trigonodon.

"

Carl von Theodori was not an “expert” as an academic, but a full-time administrative lawyer.

His publications sprang from his idealism and scientific thirst for knowledge.

He was presumably influenced by his collaborator, the catholic clergyman Augustin Geyer,

who had started the Banz Petrefakten Sammlung (fossils collection), to follow the cataclysm theory promoted by the French natural scientist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832).

Cuvier postulated that major catastrophes repeatedly destroyed a large part of living beings in the history of the earth and

new life emerged from the remaining species in subsequent phases.

Today, 170 years later, paleontologists “know” much more about this animal and its living environment.

The Banz ichthyosaur could never have been smashed against a cliff of the Keuper land,

as the Keuper sandstones are part of the uppermost Trias Formation and are deeply buried in the Banz region by the Jura Formation

of which the Lias is the lowermost member.

Note: Keuper - a lithostratigraphic unit in the subsurface of large parts of west and central Europe.

The Keuper consists of dolomite, shales or claystones and evaporites that were deposited

during the Middle and Late Triassic epochs (about 220 million years ago).

During the Lias time (from about 205 to 180 million wars ago) the northern portion of the supercontinent Pangaea

started to split up into the North American and Eurasian Plates.

The gap between the two plates was filled by waters of the Tethys Sea.

The sediments containing the fossils of Banz, Holzmaden,

Bad Boll and those of other European areas were deposited during the Toarcian oceanic anoxic event (approx. 183 Myr ago)

when carbon-rich organic plant material mixed with silt was transported by rivers into the shelf areas of the advancing Tethys Sea

and deposited as black shales and, thus, causing anoxic conditions at the bottom of the Toarcian Sea.

Anoxic conditions mean there is no oxygen (O2) and a raised level of free hydrogen sulphide (H2S) in the bottom sea water.

The oxygen is used up in decomposing organic matter – but too much organic matter was coming into the basin.

If an animals like ichthyosaurs dive into this deadly zone chasing after prey they would suffocate.

This happened probably to the Banz ichthyosaur.

The damage observed by Theodori on the skeleton were probably caused by chemical processes, bacterial activities,

bottom water flows and damage during the excavation, losses in transport and during preparation and mounting

and had nothing to do with a dramatic violent death.

Ichthyosaurus trigonodon is called

Temnodontosaurus trigonodon today.

It is a one of the largest ichthyosaurs with a length of 12 meters and the animal

had the largest known eyes of any living or prehistoric animal.

Its eyes were up to 26cm in diameter, as big as a football.

Very well-preserved fossils of

Temnodontosaurus trigonodon are on display in Natural History Museum

of Stuttgart.

[R1g]

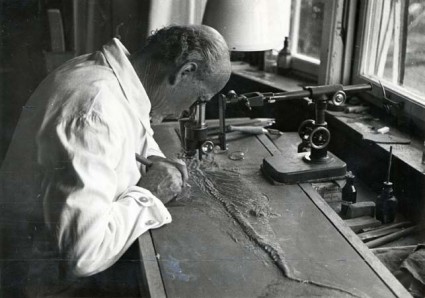

The next important stage of paleobiological study of ichthyosaurs came in the late 1880s,

when famous German preparator, Bernhard Hauff,

who was one of the first fossil preparators who worked with the stereo microscope,

devised a preparation

technique that did not destroy the thin layer of preserved soft tissues surrounding many

ichthyosaurs fossils.

His exposure of a 1.20 meter long ichthyosaur with fossilized skin and muscle residues was a sensation in 1892:

now the outlines of these sea creatures could be accurately reconstructed.

One of the more striking features revealed by this preparation technique was that ichthyosaurs had a crescent-shaped caudal fin.

This specimen led to the recognition that ichthyosaurs had a body shape more similar to that of dolphins or sharks than

to crocodiles, and was fundamental in interpreting the way of life of these animals.

Several thousand well-preserved ichthyosaurs have been found at Holzmaden

since the 1880's and prepared by the technicians at the Museum.

They can be seen in many museums at home and abroad.

The most beautiful specimens were kept by Berhnard Hauff for display in his own museum.

It opened in 1937 and was replaced by a modern building in 1971.

[R9]

In XX

th and XXI

st centuries the study of ichthyosaurs continues.

Many new discoveries were made.

Fossils of ichthyosaurs were found worldwide, including many locations in Europe,

not only Germany and UK; North America and Caribic; Australia; China and Japan, and even Spitsbergen in Norway.

Many questions about the biology of these animals have been answered, but there are also many questions left to answer.

Timeline of events mentioned in this article:

A more detailed timeline on ichthyosaur research can also be found on

Wikipedia

1602

Johannes Bauhinus published the book “A Resort book and historical Description of the

miraculous power and effect of the miracle fountain and healing baths to Boll", also known by the short name

"the BadBook", with an illustration of a tooth from a marine reptile found near Bad Boll.

Nowadays many fossils of marine animals, include several hundred ichthyosaur fossils

are known from this region.

1699

Edward Lhuyd (in walisischer Standardorthographie: Llwyd)

published a book called “Lithophylacii Britannici Ichonographia".

The book contained images of an unrecognized Ichthyosaur's vertebrae incorrectly identified as

belonging to fish, which he called as Ichtbyospondyli.

1708

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer published a book

"Piscium Querelae Et Vindiciae", in Latin, where he

shows two ichthyosaur's vertebrae which he assigned to a

remnant (leg bone) of a human who drowned during the biblical flood.

Johann Jakob Baier published a book

"Nuremberg fossil record or brief description of the fossils and Minerals of the Territory of

Nuremberg and its neighborhood”, in Latin,

where he shows two ichthyosaur's vertebrae which he assigned to a fish.

1749

Albert Mohr found, in Bad Boll, the first skeleton of an ichthyosaur.

The skeleton was without head and neck, but with an embryo.

Mohr thought that it was a ray-like fish and did not pay much attention to it.

1811

Joseph Anning, the younger brother of famous Mary Anning found a skull of an ichthyosaur on the coast of Lyme, England.

1812

Mary Anning, found a torso (postcranium) of an ichthyosaur, not far away from the place where her brother discovered the skull.

1814

Sir Everard Home, described the ichthyosaur discovered by Mary and Joseph Anning in

the first scientific description of an ichthyosaur:

"Some Account of the fossil Remains of an Animal more nearly allied to Fishes than any of the

other Classes of Animals”.

In this article, he did not give the specimen a name, but instead called the fossil a crocodile-like animal.

1817

Charles Koenig, curator of the Natural History Department of the British Museum,

used the term ichthyosaurus in the Museum’s list of fossils.

This is the first appearance of the term ichthyosaur in the professional literature.

1819

Sir Everard Home, reevaluated the Anning specimens and changed his opinion on what the animal was.

He came to the conclusion that it was an intermediate form between salamanders and lizards and proposed the name Proteosaurus.

Even though it had precedent over the Ichthyosaurus name, proposed but not piblished by Koenig, it was rarely used and has become a forgotten name

1821

The first complete ichthyosaur skeleton was found by Mary Anning and her brother.

The first genus Ichthyosaurus was named by de la Beche & Conybeare.

1822

Willian D. Conybeare described ichthyosaurs as reptiles, based on the second Ichthyosaur found by

Mary Anning the previous year and assigned ichthyosaurs to the Class Reptilia.

1824

Georg Friedrich von Jaeger described the ichthyosaur skeleton found by Albert Mohr in 1749, as a skeleton of

ichthyosaurs in an article in Latin.

1828

Georg Friedrich von Jaeger translated, due to lots of interest, his article from Latin to German.

1830

Henry de la Beche created the first reconstruction of a scene of prehistoric life

in the watercolor “Duria Antiquior” that include the first reconstruction of ichthyosaurs as crocodile-like animals.

1841

A skull and some bones of a giant ichthyosaur were found at Banz Monastery in Bavaria, Germany

1842

Georg Friedrich von Jaeger, suggested that ichthyousaurs might have given birth to live young.

1843

Carl Theodori published his first, brief description of the ichthyosaur from castle Banz and named it

Ichthyosaurus trigonodon.

1846

Joseph Chaning Pearce published an article where he concluded that ichthoysaurs were viviparous reptiles.

1854

Carl Theodori published a very detailed article, about the ichthyosaur from castle Banz.

"Description of the Colossal Ichthyosaurus trigonodon from the local fossil collection at Banz

along with synoptic representation, with illustrations in natural size".

1892

Bernhard Hauff developed a technique for preparing fossil specimens of ichthyosaurs

that allowed better viewing of the soft-bodied impressions around the skeleton of the animal.

1908

Wilhelm von Branca published an article "Nachtrag zur Embryonenfrage bei Ichthyosaurus"

(in English: "Addendum to the embryo question of Ichthyosaurs")

where he argued his theory about ichthyosaur's cannibalism.

1922

Baron Frierich von Huene reviewed all known genera and species of Ichthyosaurus and renamed

Ichthyosaurus trigonodon to Temnodontosaurus trigonodon

1927

First, fragmental, fossils of the early ichthyosaur Utatsusaurus discovered in Japan

1982

Japanese paleontologist discovered some skeletons of primitive Ichthyosaur Utatsusaurus

1989

Dr. Ronald Boettcher published the results of his study on over 40 skeletons of

Stenopterygius with young. In the study, he concluded that ichthyosaurs were not cannibals.

1995

The skeletons of Utatsusaurus were removed from the rock, cleaned and studied.

These fossils allowed the researchers to clarify the origin of ichthyosaurs from land-living reptilian

ancestors – as Utatsusaurus was essentially a lizard with fins.

2004

The largest Ichthyosaur species recorded to date Shonisaurus sikanniensis was

discovered in British Columbia, Canada.

2016

Some fragmental fossil of Ichthyosaur was discovered on the beach at Lilstock, Somerset.

Scalling of these bones suggest the ichthyosaur has a length of about 25-26 meters,

around the average size of a blue whale.

Ichthyosaurs in Philately

The oldest philatelic items depicting Ichthyousaurs known to the author to date (2021) are German postcards from the end

of XIX

th century - "Greeting from

castle Banz".

The oldest item in the author’s collection was posted in 1897, but it is likely that even earlier versions may exist.

Fossils of Ichthyosaur, Pterosaur and prehistoric crocodile Mystriosaurus on postcards of Germany, Reichspost, 1890s to 1930s

Fossils of Ichthyosaur, Pterosaur and prehistoric crocodile Mystriosaurus on postcards of Germany, Reichspost, 1890s to 1930s

These postcards exist in several color and design variations.

Many of them shows not only the famous skull of an ichthyosaur but also some other fossils from the region:

Ammonites,

Pterodactyl (described by Theodori in 1830) and prehistoric crocodile

Mystriosaurus.

The ichthyosaur skull, the biggest ichthyosaur skull discovered in Europe to date (2021),

is the skull drawn by Carl Theodori for his publication in 1854 on the discovery of

Temnodontosaurus trigonodon

fossils near Monastery Banz in 1842.

The drawing of the Ichthyosaur skull made by Carl Theodori foe his article about Temnodontosaurus trigonodon fossils discovery near Monastery Banz.

The skull was drawn in the same scale as the original fossil (over 2m long).

The drawing of the Ichthyosaur skull made by Carl Theodori foe his article about Temnodontosaurus trigonodon fossils discovery near Monastery Banz.

The skull was drawn in the same scale as the original fossil (over 2m long).

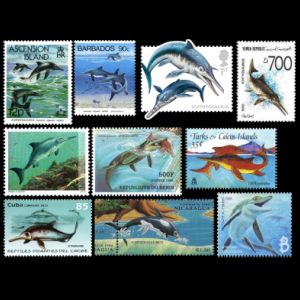

More than 100 ichthyosaurs species are known to date.

Some of these species are depicted on international philatelic objects such as postage stamps

and commemorated postmarks.

Undesirable stamps are excluded

Triassic ichthyosaurs depicted on Philatelic items

Notes:

[P1]

Utatsusaurus is one of the most primitive grades of ichthyosaurs - a basal ichthyosaur.

Utatsusaurus hataii is the earliest-known ichthyopterygian which lived in the Early Triassic period (between 245 and 250 million years ago.

Its body shape is closer to lizards and less like the more dolphin-shaped bodies of later, more advanced ichthyosaurs.

Philately:

This landscape postmark of Miyagi Prefecture of Japan

is the only philatelic item that shows the basal ichthyosaur genus Utatsusaurus.

The postmark was available between June 1989 and November 2011 when

the post Bureau was destroyed by earthquake.

The museum building was destroyed, but the ichthyosaur fossils survived, as it was transported to the safe place in advance.

[P2]

Mixosaurus ("mixed lizard")

is an extinct genus of Middle Triassic (Anisian to Ladinian, about 250-240 Mya) ichthyosaur.

Mixosaurus fossils have been found almost worldwide.

Several hundred individual of

Mixosaurus cornalianus have been found from the Middle Triassic

of Monte San Giorgio and the Tessin areas on the border of

Italy

and

Switzerland.

Mixosaurus was a transitional form between primitive ichthyosaurs with eel-like elongated body like

Cymbospondylus and the more modern forms that had a shape similar to today's dolphins.

Mixosaurus was a small to medium-sized ichthyosaur, not growing more than 2 meters in total length

with small species not growing more than 1 meter.

It possessed a long tail with a low fin, suggesting it could have been a slow swimmer.

Philately:

[P3]

Shonisaurus is an ichthyosaur genus from the Middle Triassic,

(Carnian stage from 237 to 227 million years ago) of North America.

With lengths from 15 to 21 meters, the genus was one of the largest ichthyosaurs.

Philately:

Jurassic ichthyosaurs depicted on Philatelic items

| Ichthyosaurus communis [P4] |

Ophthalmosaurus [P5] |

Stenopterygius [P6] |

|

|

|

| Suevoleviathan [P7] |

|

|

|

Notes:

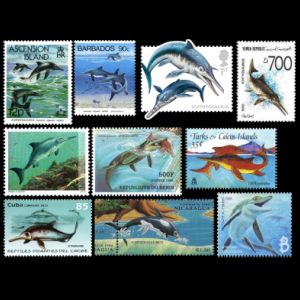

[P4]

Ichthyosaurus communis - a large skull fragment from the early Jura, in Frick,

Switzerland.

The layers from which the fossil originated have estimated age of 190 million years.

Philately:

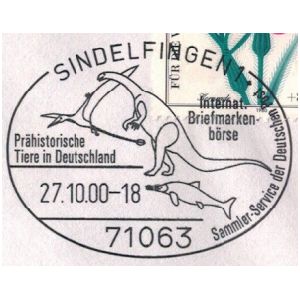

- Ascension Island 1994: MiNr.: 623, Scott: 575; with overprint : MiNr.: 628, Scott: 575

- Barbados 1993: MiNr.: 836, Scott: 855b

- Benin 1998: MiNr.: 1046, Scott: 1085g

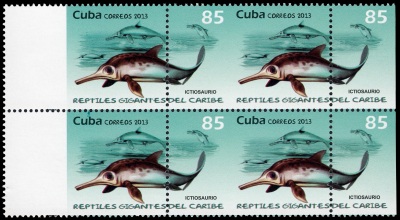

- Cuba 2013: MiNr.: 5683, Scott: 5389

- Nicaragua 1994: MiNr.: 3382, Scott: 2041k

- Transnitria 2016 (official stamp of unrecognized territory:

Transnitria)

- Turks and Caicos Islands: MiNr.: 1213, Scott: 1120c

- Switzerland 2010: MiNr.: 2168, Scott: 1395

- UK 2013: MiNr.: 3527, Scott: 3229

- Yemen 1990: MiNr.: 29, Scott: 555

[P5]

Ophthalmosaurus (meaning "eye lizard" in Greek) is

an ichthyosaur of the Jurassic period (165–160 million years ago).

Possible remains from the Cretaceous, around 145 million years ago, are also known.

Named for its extremely large eyes, it had a graceful 6 meters long dolphin-shaped body,

and weighed approximately 930 kg, its nearly toothless jaw was well adapted for catching squid.

Major fossil finds of this genus have been recorded in Europe and North and South America.

Philately:

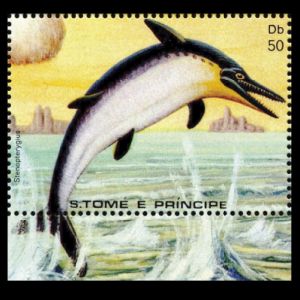

[P6]

Stenopterygius is a genus of ichthyosaurs from the

early to middle Jurassic (Toarcium - Aalenium).

Fossils of the genus were found in England, France, Germany, Switzerland and Luxembourg.

Stenopterygius is the most common ichthyosaur genus of the Holzmadener Posidonia slate.

Hundreds of very well preserved skeletons of the animal, include pregnant specimens,

with up to 11 embryos inside, were found there.

One well-preserved fossil of

Stenopterygius preserves traces of skin,

from which the animal's coloration was discovered to be counter-shaded

(darker on the back than the underbelly)

Philately:

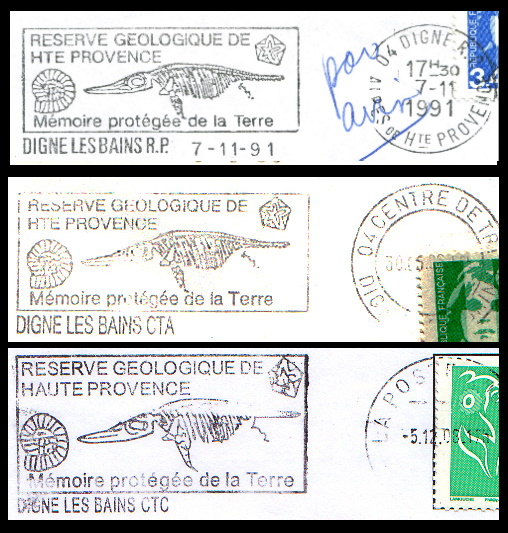

[P7]

Suevoleviathan is an extinct genus of primitive ichthyosaur found

in the Early Jurassic (Toarcian) of Holzmaden, Germany and France.

The genus

Suevoleviathan probably reached a total length of up to 4 meters.

Suevoleviathan was unique among ichthyosaurs in that it retained relatively large forefins.

Philately:

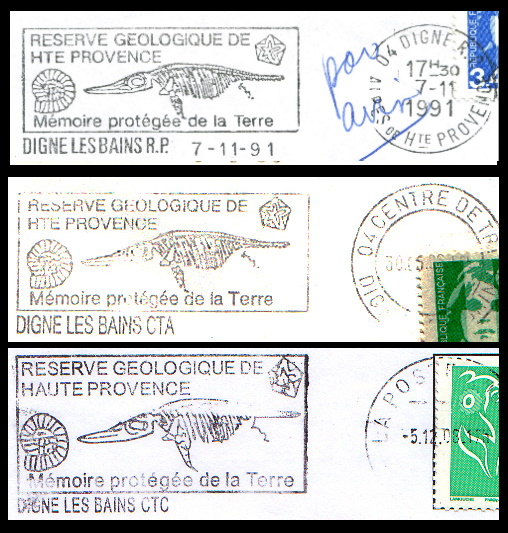

This landscape postmark of

France

is the only philatelic item that shows

Suevoleviathan.

Three major varieties of this postmark were produced with different locations, changes in the font and text, and the year when used.

- Digne Les Bains CTA

- Digne Les Bains CTC

- Digne Les Bains R.P.

Cretaceous ichthyosaurs depicted on Philatelic items

Notes:

[P10]

Platypterygius

is an ichthyosaur of the family

Ophthalmosauridae.

The ichthyosaur lived from the Early Cretaceous period (Hauterivian stage)

to the earliest Late Cretaceous period (Cenomanian stage) and had a very wide distribution,

including Australia, where it was found with remains of sea turtles and birds (

Nanantius) in its guts.

Platypterygius reached a length of about 7 metres, had a long snout and a powerful finned tail.

Philately:

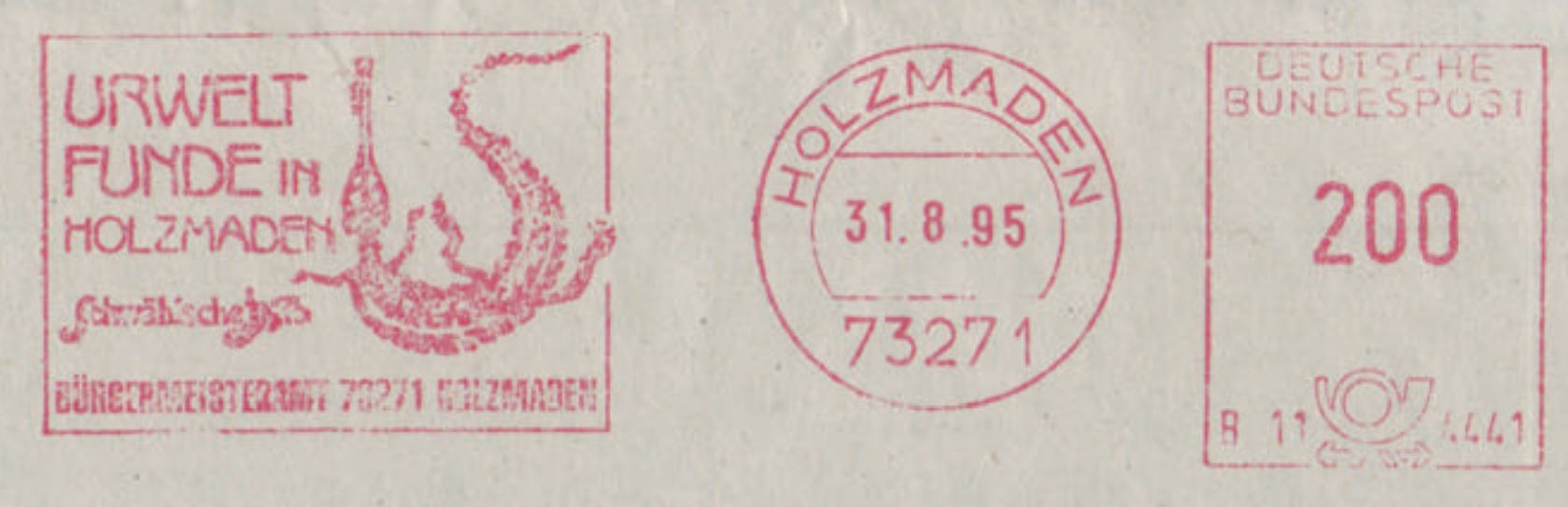

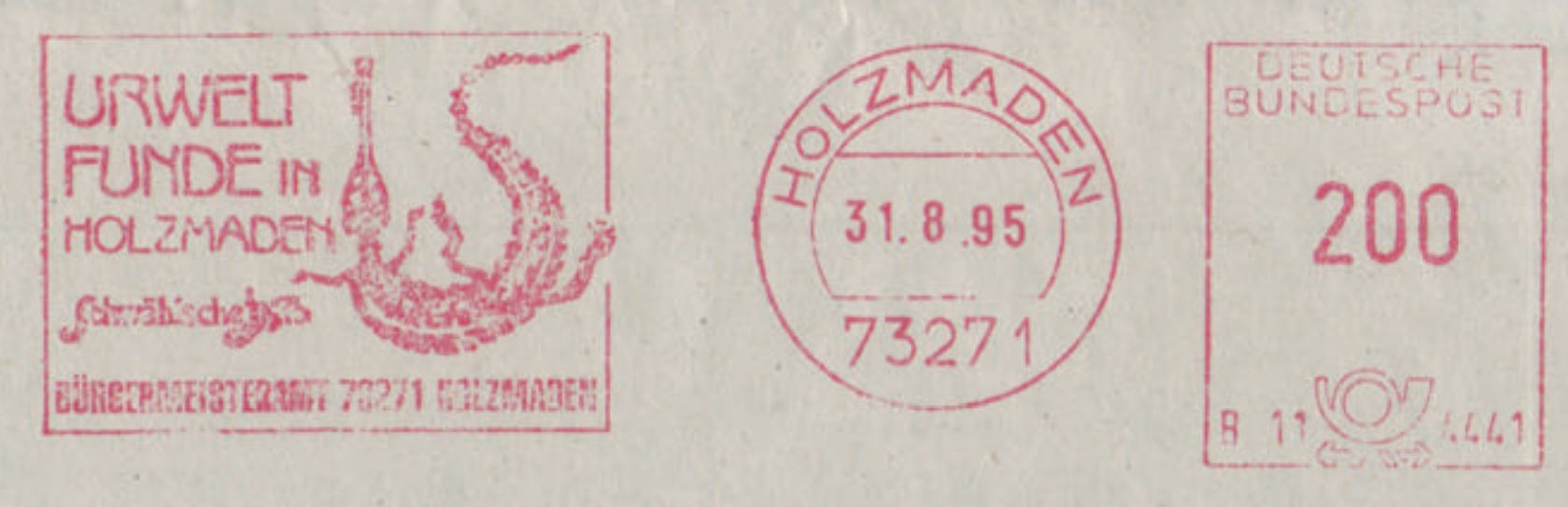

This German postmark

is the only philatelic item that shows Platypterygius.

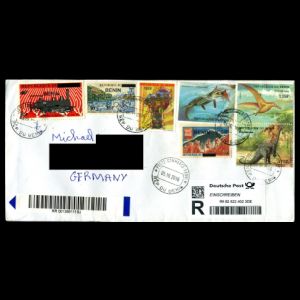

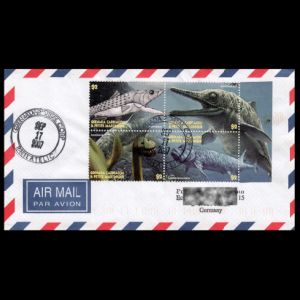

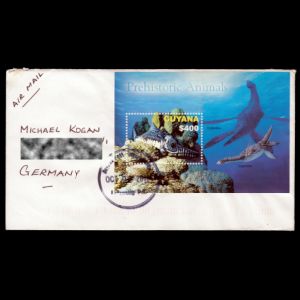

Some circulated covers with Ichthyosaurs on stamps or cachet

Some philatelic material with unidentified Ichthyosaurs

References:

[R1]

Ichthyosaur (general information):

- Britannica,

Wikipedia

-

Sea dragons: predators of the prehistoric oceans

, Richard Ellis, ISBN 0-7006-1269-6

Rulers of the Jurassic

by Ryosuke Motani. Scientific America 2000.- "The Evolutionary History of Ichthyosaur", by Dean Lomax

- "Dinosaur Bones from Late Triassic UK Are Jaw Bones from Giant Ichthyosaurs", by Dean Lomax

- Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart (SMNS)

-

Terrestrial Origin of Viviparity in Mesozoic

Marine Reptiles Indicated by Early Triassic Embryonic Fossils

, by Ryosuke Motani, Da-yong Jiang, Andrea Tintori,

Olivier Rieppel, Guan-bao Chen.

-

Evolution of Fish-Shaped Reptiles (reptilia: Ichthyopterygia) in Their Physical Environments and Constraints

, by Ryosuke Motani.

- Raeuber im Jurameer (in German)

- Die Urzeit-Biester aus der Tiefe (in German)

- Ichthyosaurier: Urzeit-Monster der Meere (in German)

-

Fischsaurier - einmal Landleben und zurueck, by Paul Martin Sander from University of Bonn. (PDF in German)

[R2]

Ichthyosaurs genera

(due to the fact there are over 100 Ichthyosaurs species known to date and new species defined every year,

the following list contain only the species that are mentioned in this article):

|

|

Ichthyosaurs on stamps of Cuba 2013 - perforation error, MiNr.: 5683, Scott: 538

|

- Ichthyosaurus latifrons: