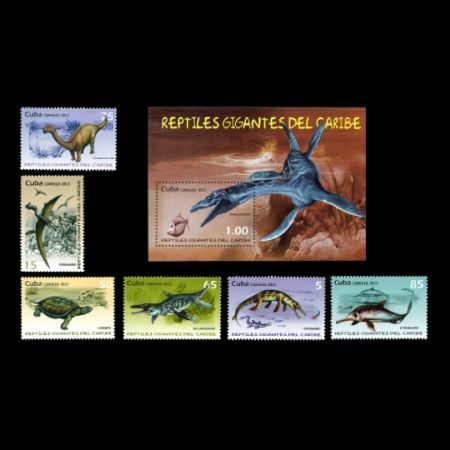

Cuba 2013

"Giant Reptiles of the Caribbean"

| Issue Date |

03.04.2013,

but arrived in the post offices in October-November 2013.

|

| ID |

Michel: 5678-5683, Bl. 299;

Scott: 5384-5389, 5390;

Stanley Gibbons: 5809-5814, MS5815;

Yvert et Tellier: 5178-5183, BF301;

Category: pR

|

| Design |

|

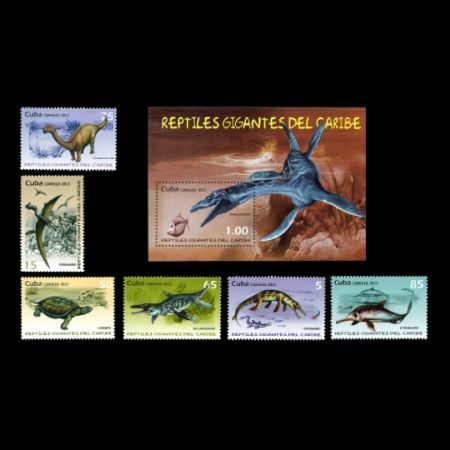

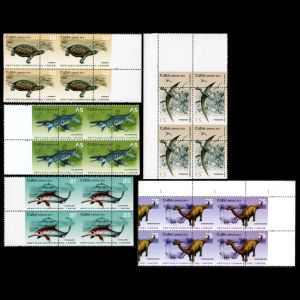

| Stamps in set |

7 (6 stamps + Block) |

| Value |

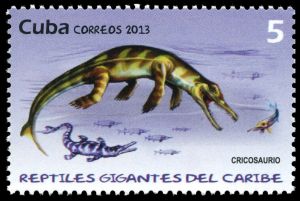

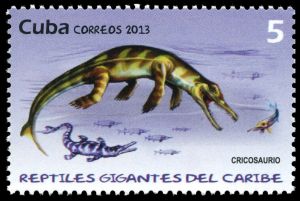

c05 - Cricosaurus

c15 - Pterosaur

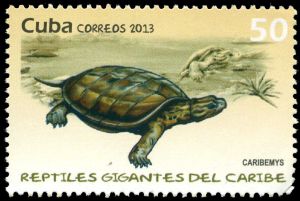

c50 - Caribemys

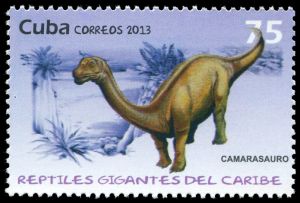

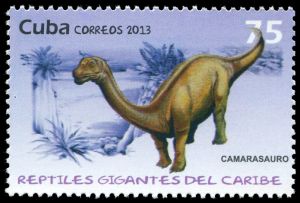

c75 - Camarasaurus

c65 - Gallardosaurus

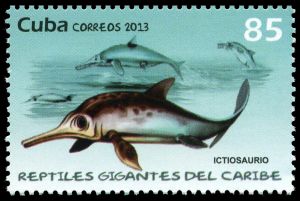

c85 . Ichthyosaur

p1 - Vinialesaurus

|

| Emission/Type |

commemorative |

| Places of issue |

Habana |

| Size (width x height) |

stamps: 49mm x 21mm,

Souvenir-Sheet: 108mm x 76mm.

|

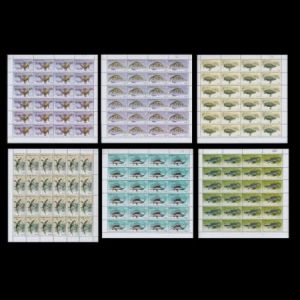

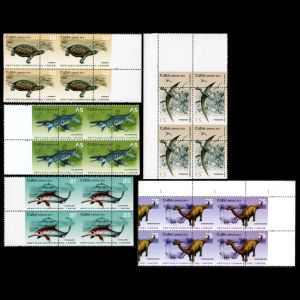

| Layout |

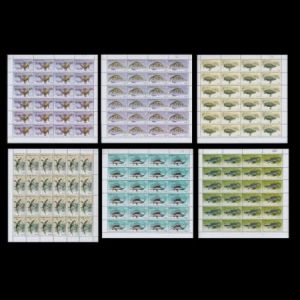

Sheets of 24 stamps, Souvenir Sheet |

| Products |

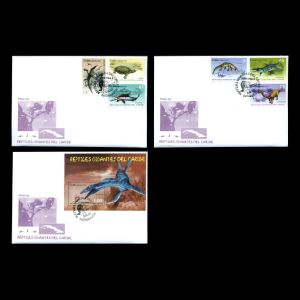

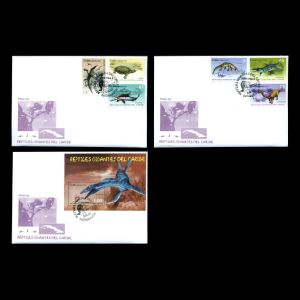

Post-cancelled FDC x1

|

| Paper |

|

| Perforation |

12.50 12.25 |

| Print Technique |

Offset lithography |

| Printed by |

|

| Quantity |

|

| Issuing Authority |

|

Initially, the Post Authority of Cuba planned to issue the set of 6 stamps and 1 Souvenir Sheet

"Giant Reptiles of the Caribbean" on April 3

rd, 2013.

However, due to some technical reasons the sales of the stamps started half a year later, even

though

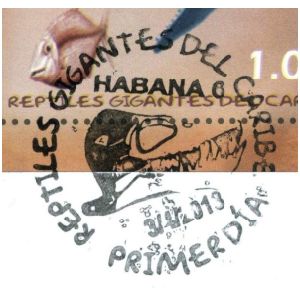

postmark on the FDC

remained dated 3/4/2013.

These stamps show prehistoric animals whose fossilized remains have been found on the

territory of the island of Cuba.

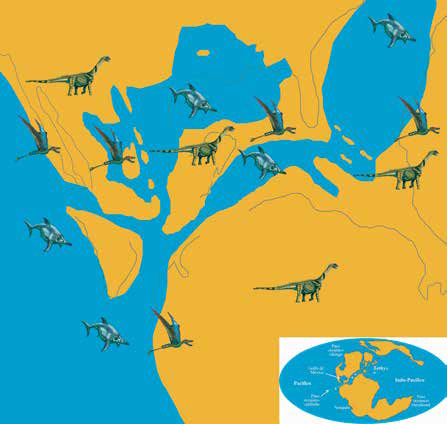

The Caribbean Zone during the Cretaceous was a marine realm occupied by ammonites,

ichthyosaurs, and

other sea creatures

|

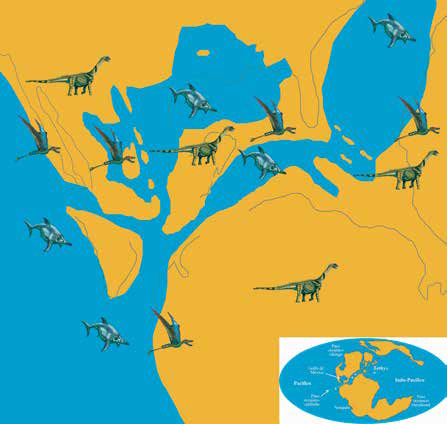

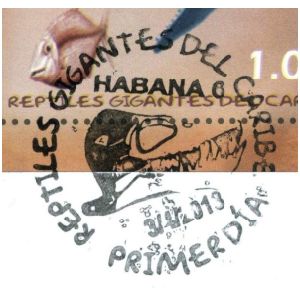

A paleogeographic map of Cuba during the Mesozoic era.

Image credit

Ceballos Izquierdo, Yasmani & Iturralde-Vinent, Manuel. (2018).

Prehistoricos del Caribe.

10.13140/RG.2.2.19071.30889.

Similar, but mono-color map was depicted on a

cachet

of an FDC

|

Latest paleontologic discoveries shows the presence of dinosaurs and pterosaurs too,

whose fossils have been found in the mountains of western Cuba,

along with fossil bones and skulls of marine reptiles from the Late Jurassic.

Remains of prehistoric reptiles were found in Cuba during the first half of the 20

th century

at several localities in the Sierra de los Organos and Sierra del Rosario of the Guaniguanico mountain range,

located at the western side of the island.

During the 1990s, Manuel Iturralde-Vinent, from the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Cuba, started

gathering information about those specimens, and made a detailed catalogue of Jurassic reptile-bearing

localities, with a preliminary discussion of the taxonomic position of the previously published taxa.

Since the end of the 1990s there has been a close collaboration between Iturralde-Vinent and palaeontologists

of the Museo de La Plata, in Argentina, that includes fieldwork, preparation of the specimens and

corresponding systematic studies.

Dr. Iturralde-Vinent explained in one of his interviews that the identification of

Cuban species is a very complex task, because most fossils are isolated bones and

fragments of bones instead of complete skeletons.

This poor preservation is due to the humid climate of Cuba which enhances weathering

of these fossils when they are exposed at the surface.

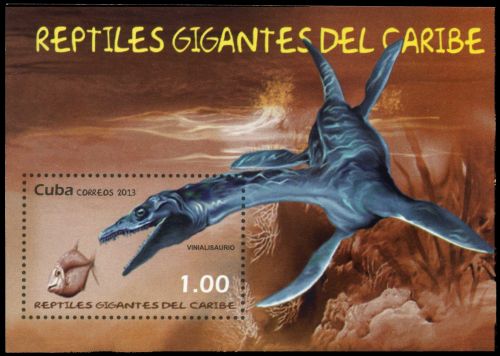

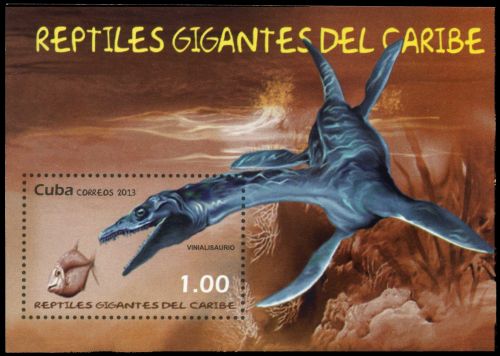

The Souvenir-Sheet shows a

long-necked reptile Vinialesaurus,

of a plesiosaur from the Late Jurassic Jagua Formation.

The Jagua Formation is a Late Jurassic (middle to late Oxfordian)

geologic formation in Pinar del Río Province, western Cuba.

Plesiosaur, pliosaur, pterosaur, metriorhynchid, and turtle remains are among the

fossils that have been recovered from its strata.

|

|

Vinialesaurus on stamp of Cuba 2013, MiNr.: Bl. 299, Scott: 5390s.

|

The type species is

Vinialesaurus caroli, first described as

Cryptocleidus caroli

by

Carlos de la Torre and Rojas in 1949, and

redescribed by Gasparini, Bardet and Iturralde-Vinent in 2002.

The authors of the 2002 paper considered Vinialesaurus distinct enough from

Cryptocleidus to warrant its own genus.

The name

Vinialesaurus honors Viñales, the town in western Cuba where the

fossils were discovered.

The Viñales Valley has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since November

1999, for the outstanding karst landscape and traditional agriculture as well as

vernacular architecture, crafts and music.

On of the attraction of the village is Museo Paleontológico.

These fossils consist of a mostly complete skull, jaw, and portions of the vertebrae.

The strength of their body and their long, powerful swimming fins suggest that they

moved from the depths of the ocean to the coastline.

They were endowed with dangerous teeth, with two or three rows of pointed teeth like thorns.

|

|

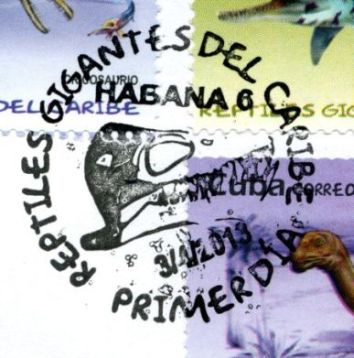

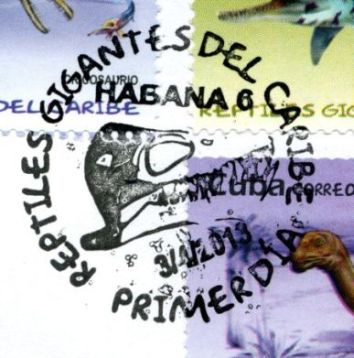

Skull of Vinialesaurus on commemorative postmark of Cuba 2013

|

Their heads were small compared to their body size.

Due to this fact, the paleontologists think that it had to spend considerable time

eating as it was only able to eat small prey such as small fish and reptiles.

The souvenir sheet shows an example of this behavior - the plesiosaur is shown preying

upon a small fish.

Another big marine reptile, shown on the stamps, is

Gallardosaurus.

Gallardosaurus is a genus of pliosaurid plesiosaur from the Caribbean Seaway.

The Caribbean Seaway, opened as a corridor only since the Late Jurassic, allowed the exchange of

pelagic marine biota between the Western Tethys and the Eastern Pacific realms.

|

|

Gallardosaurus on stamp of Cuba 2013, MiNr.: 5681, Scott: 5387.

|

The genus contains the single species

Gallardosaurus iturraldei, which

was found in Late Jurassic (middle–late Oxfordian age) rocks of the Jagua Formation

of western Cuba.

The specimen had been discovered in 1946 by Cuban farmer Juan Gallardo about 8 kilometres east of Viñales,

Pinar del Río, north-western Cuba, but the specimen was not prepared until 2006.

The generic name honors the discoverer (Juan Gallardo who for many years toured the Guaniguanico Mountain

Range in Pinar del Río in search of representatives of life in the remote past).

Gallardosaurus iturraldei, is considered one of the greatest predators of the

prehistoric Caribbean, since they could feed on any other marine animal of that time.

This species probably seasonally migrated across the Caribbean Seaway, while acting

as an active predator taking advantage mainly of the large amount of migrating

(nectonic) fish.

They hunted by ambush, hiding in the depths and attacking prey that swam close to the

surface.

Its body was about three or four meters long, with a short neck, a very prominent head and gigantic jaws.

Their jaws were endowed with sharp crisscrossed teeth, which prevented the escape of the prey once bitten.

It had no enemies, unless it was a very young specimen.

The lack of fusion in some of the vertebrae, of the Cuban species, suggests the individual was not

fully grown when it died.

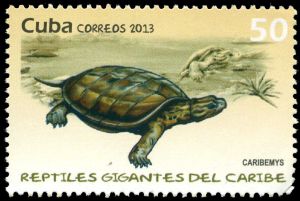

The coastal aquatic turtle called

Caribemys oxfordiensis or "

Caribbean tortoise"

was common in the Caribbean Seaway too.

|

|

Caribemys oxfordiensis on stamp of Cuba 2013, MiNr.: 5680, Scott: 5386.

|

The tortoise swam in the sea looking for food, and could ascend to the coast to spawn and shelter,

like its congeners today, because it had legs with fins to swim and nails to climb to land.

Caribemys was small tortoise, about 35 centimetres long, and it's almost

complete skeleton, without the skull, was collected by the peasant and "fossil hunter"

Juan Gallardo, near Viñales, in Pinar del Río, back in the 1950s.

|

|

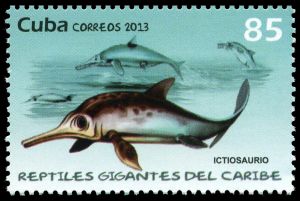

Ophthalmosaurus on stamp of Cuba 2013, MiNr.: 5638, Scott: 5389.

|

In the deeper waters, swam

icthyosaurs

like the species

Ophthalmosaurus which were similar to modern dolphins with a tuna-like tail.

These animals were actually reptiles though, not mammals.

These were hardy animals, very fast swimmers and endowed with large eyes;

That is why they were able to dive to great depths where the luminosity is scarce.

They were like the cows of that time because, although they fed on fish and molluscs, they served as food

for other reptiles.

To date (2013), fossil representatives of at least five ichthyosaurs have been located

in the mountains of Pinar del Rio including both skull fragments and body bones.

|

|

Metriorhynchidae on stamp of Cuba 2013, MiNr.: 5678, Scott: 5384.

|

Metriorhynchidae, are a group of

marine crocodyliforms

that were perfectly adapted for life in the open sea,

thanks to glands that filtered sea salt and ensured the supply of fresh water to the animal.

These crocodiles had very powerful jaw, making them one of the top predators of their time.

To date (2013), the remains of three individuals have been found in the fossiliferous

beds of the Pinar del Rio.

Two of the specimens included fragments of the skulls with jaws.

|

|

Camarasaurs on stamp of Cuba 2013, MiNr.: 5682, Scott: 5388.

|

The first report of the presence of fossil remains of

dinosaurs in

Cuba dates to 1949, when Alfredo de la Torre y Callejas reported the discovery of a

bone 45 centimetres long, near the valley of Viñales.

|

|

Pterosaur on stamp of Cuba 2013, MiNr.: 5679, Scott: 5385.

|

The fossil was discovered in rocks what had once been coastal sediment.

That is why Alfredo de la Torre explained in his thesis that the animal must have died on land and

its dismembered remains reached the sea, perhaps driven by the current of a river or a hurricane.

Initially, he thought, the bone belongs to a

Brontosaurus or

Diplodocus dinosaur.

Later on, the bone was identified by Argentinean paleontologist, Dr. Leonardo Salgado, who cooperated

with his Cuban colleagues, as a small bone of the hand of some reptile related to

Camarasaurs.

Abundant remains of terrestrial vegetation such as fern trees, the fossil remains of at

least two species of pterosaurs—extinct flying reptiles—and marine reptile fossils

were found in the same strata.

The

pterosaurs,

Nesodactylus hespericus and

Cacibupteryx caribensis,

had the ability to travel long distances, both in search of food and to mate.

To catch the fish they made a low flight over the water, and used their jaws and teeth as a net.

The forelimbs of these animals were constituted by membranous wings, supported for the most part

by the elongation of the fourth finger.

An exclusive and different way to the design of the wings of birds and bats.

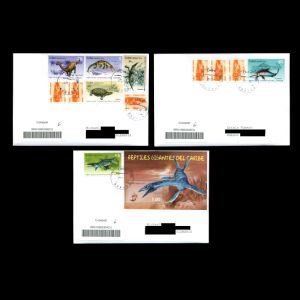

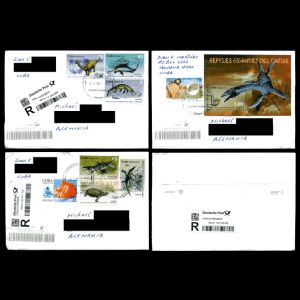

Products and associated philatelic items

| Post-cancelled FDC |

First-Day-of-Issue Postmark |

Stamp Sheets |

|

|

|

|

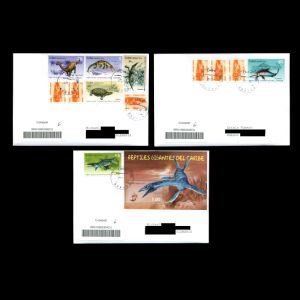

The stamps arrived at post offices in October-November 2013.

First day covers were postmarked with the initially planned April 3rd issue date.

|

|

|

|

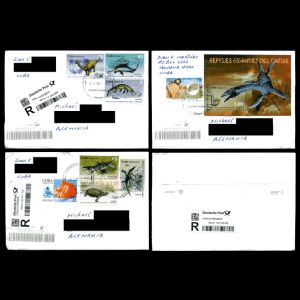

| Example of circulated covers |

|

|

|

|

| Color variants and perforation errors |

|

|

|

References

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Dr.

Peter Voice, PhD Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences,

Western Michigan University, USA, for review of a draft of this article and his very valuable comments.