Paleoanthropology

"Paleoanthropology,

also spelled Palaeoanthropology, also called Human Paleontology,

interdisciplinary branch of anthropology concerned with the origins and

development of early humans." Encyclopedia Britannica

|

|

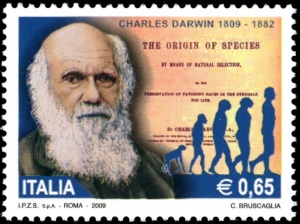

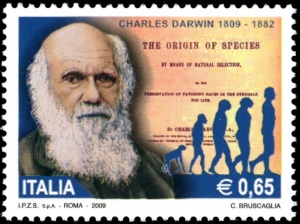

Charles Darwin

and human evolution sequence on stamp of Italy 2009, MiNr.: 3280; Scott: 2911.

|

In other worlds, Paleoanthropology or

Pal

aeoanthropology, is a science about human origin

and evolution based on fossils record, primitive (flint, stone) tools,

artifact and settlement locations.

Paleoanthropology studies the prehistoric ancestors of humankind,

referred to in a group as

hominids.

Don't miss it with Archeology and Anthropology.

Archeology - science about modern human activity through the

recovery and analysis of material culture.

Anthropology - science about modern humans and human behavior

and societies in the past and present.

Fossil can be of different types: entire, fragmented skeletons

or just a single bones or teeths, tissue or even

entire bodies preserved in permafrost, footprints etc.

|

|

|

|

|

Skull of Tchadanthropus uxoris on stamp of Chad 1966

MiNr.: 162 , Scott: 133.

|

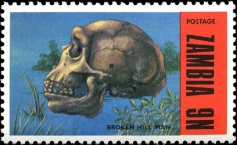

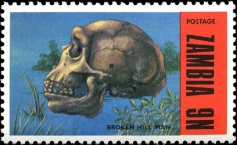

Skull of "Broken Hill Man" (Homo rhodesiensis) on stamp from "Fossils from Luangwa" set of Zambia 1973

MiNr.: 98 , Scott: 95.

|

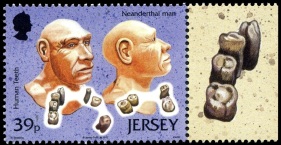

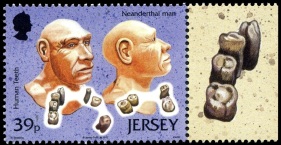

Neanderthal man on stamp from "Jersey Archaeology La Cotte de St Brelade" set of Jersey 2010

MiNr.: 15121 , Scott: 1476.

|

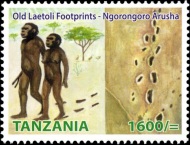

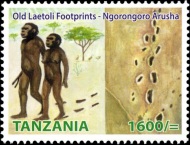

Laetoli hominids and their footprints on stamp from "Tanzania heritage sites" set of Tanzania 2014

MiNr.: 5182 , Scott: 2752.

|

Scientists who study this fossils called

Paleoanthropologists

or

Palaeoanthropologists.

They

dig for

fossils in the field, bringing them to universities, labs or

museums

where they dissect, study and assemble it.

In the field, discovering physical remains and other fossils follows

painstaking procedures similar to those archaeologists use when

uncovering cultural remains.

Once remains are discovered, they are usually sent to a laboratory or

research center where they are carefully studied, using chemical and

physical dating methods, X-Rays, MRIs, and other special tools.

Paleoanthropologists are most interested in noting how the finds are

similar and how they are different from already established ancestral

lines.

[R3]

Results of their study, allows us to restore human evolution

tree and make some

reconstruction of prehistoric hominids and humans,

as represented on many

stamps

from around the world.

A hominid, according to the Oxford Dictionary, is a primate of the family

Hominidae,

which includes humans and their prehistoric ancestors.

The

Hominidae also (at least in many hypothesized trees) includes the great apes

(Orangutans, Gorillas, and Chimpanzees).

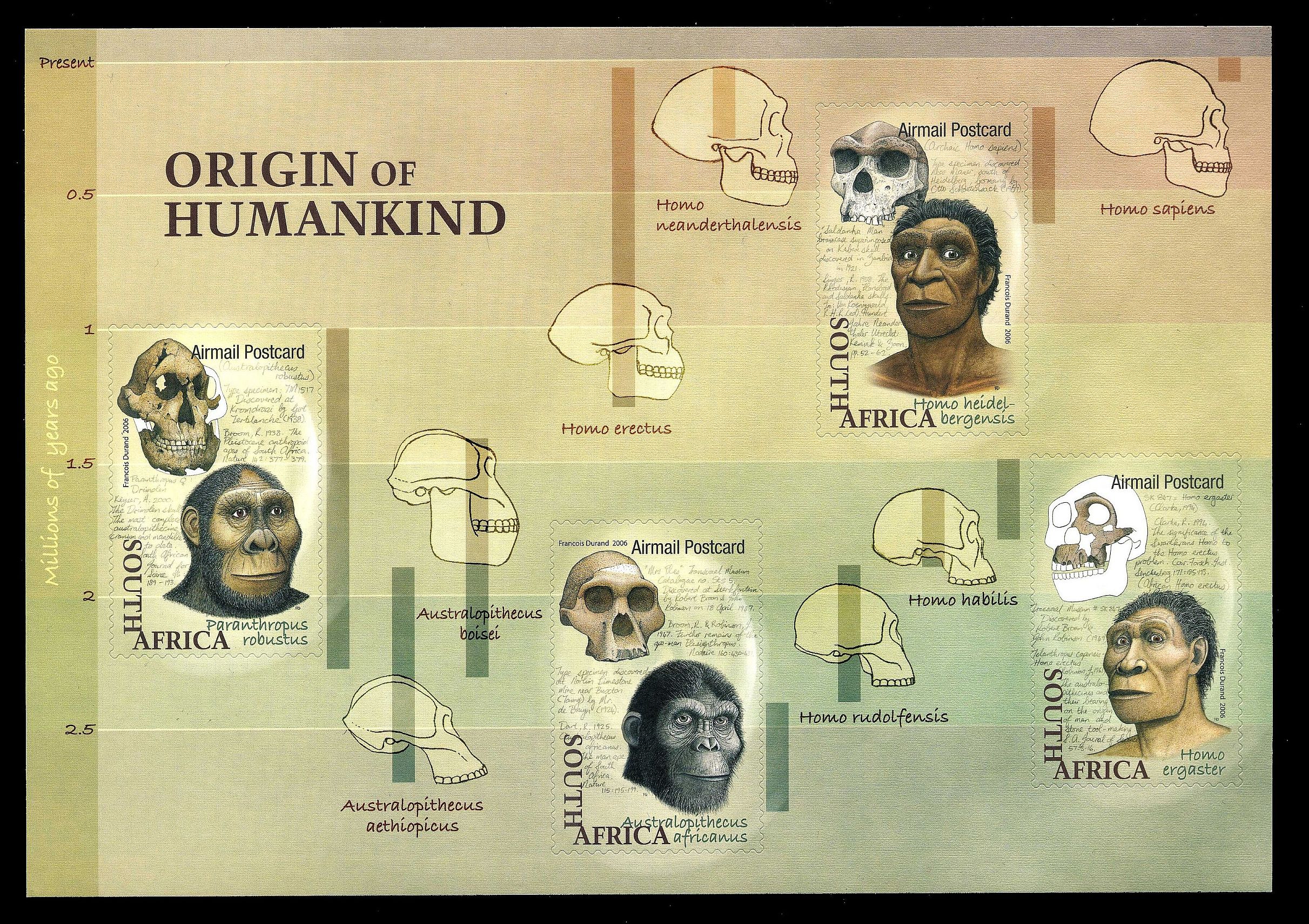

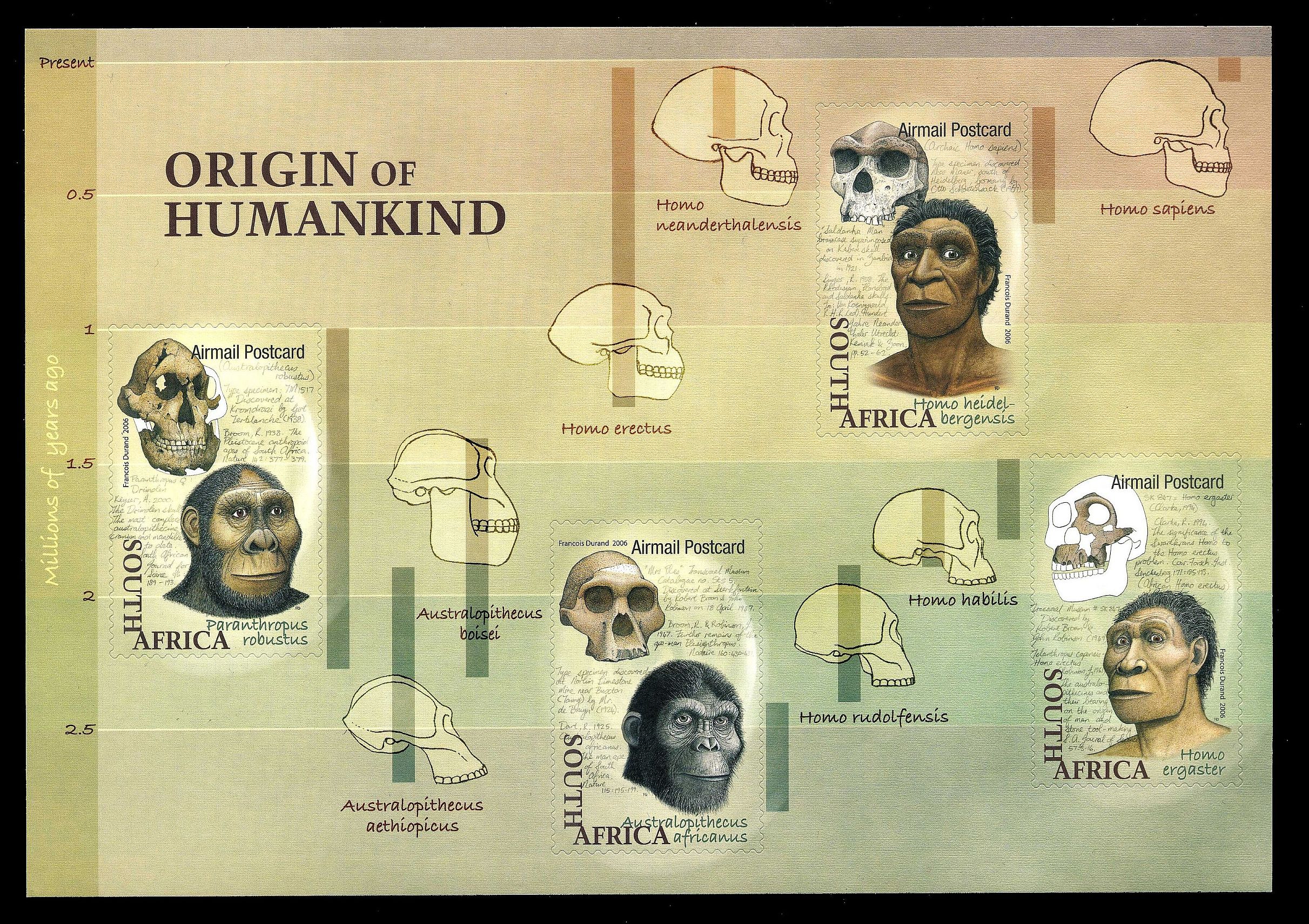

Human evolution on stamps of South Africa 2006

The modern field of Palaeoanthropology began in the 19

th century with the discovery of

a partial skeleton in the Neanderthal Valley,

near Dusseldorf in

Germany.

In August, 1856,

the partial skeleton

of an ancient man was discovered in a German cave,

the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte, in the Neandertal valley, 13 km east of

Düsseldorf.

|

|

Johann Carl Fuhlrott with skull of Neanderthal on commemorative postmark of Germany from 2006,

|

The fossils were given to Johann Carl Fuhlrott, a local teacher and amateur naturalist,

who recognized the remains as those of a human who significantly differed from modern man.

The report about the discovery brought the find to the attention of two Bonn professors of anatomy,

Hermann Schaaffhausen and August Franz Josef Karl Mayer.

They contacted Fuhlrott and asked him to send the bones to them.

Six months later Schaaffhausen and Fuhlrott presented results of their study to the members

of the Natural History Society of the Prussian Rhineland and Westphalen.

They concluded that the bones belonged to a representative of a native tribe who had inhabited

Germany before the arrival of the ancestors of modern humans.

The news was a worldwide sensation.

Schaaffhausen continued to study these fossils and published results of his research in

several international scientific magazines.

In 1863, an Anglo-Irish geologist at Queen's College Galway, William King, was the first to propose

that the bones found in the German valley of Neandertal in 1856 were not of

Homo sapiens,

but of a distinct species:

Homo neanderthalensis.

He proposed the name of this new species at a meeting of the British Association in 1863,

with the written version published in 1864.

The fossils from the Neanderthal Valley were not the first Neandertal fossil discovery.

Other Neandertal fossils had been discovered earlier, but their true nature and significance

had not been recognized, and, therefore, no separate species name was assigned.

The Publication of

Charles Darwin's

"

Origin of Species" in 1859 awoke public and scientific

interest in the origin of humans.

Naturalists started to search for bones of unknown humankind in the field and in

the museum collections around the world.

|

|

Discovery of Neanderthal's skull in Forbes' Quarry, in Gibraltar in 1859

|

One of the rediscovered fossils was the skull found in

Gibraltar

in 1830 at Forbes' Quarry, during quarrying operations in brecciated talus on the north face of

the Rock of Gibraltar.

The skull was presented to the Gibraltar Scientific Society by its secretary,

Lieutenant

Edmund Henry Réné Flint, on 3 March 1848,

but its significance was not recognized until after the discovery of the skull from the Neandertal Valley.

The skull is known as

Gibraltar-1 today,

was brought out of obscurity, and presented at a meeting in the British Association for the Advancement

of Science in 1864, at Norwich, England.

Charles Darwin was not present, but the skull was later examined by both Darwin and

Thomas Huxley,

who concluded the skull was that of an extinct human species.

Charles Darwin did however make fleeting reference to Gibraltar-1 in his 1871 publication,

“

The Descent of Man”.

The skull is dated to between 30 thousand and 50 thousand years old.

A cast of the skull can be viewed at the Gibraltar Museum – the original is on display

in the Human Evolution gallery of the Natural History Museum in London.

Lately, the skull has become the subject of debate about whether to return it to Gibraltar or not.

In 1912, Charles Dawson, a British amateur archaeologist, claimed that he had discovered the "missing link"

between early apes and man.

He contacted Arthur Smith Woodward, Keeper of Geology at the Natural History Museum in London, stating he had found a section

of a human-like skull in Pleistocene gravel beds near

Piltdown, East Sussex.

|

|

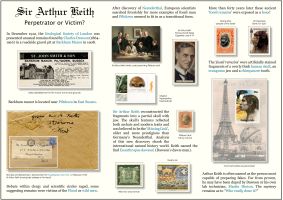

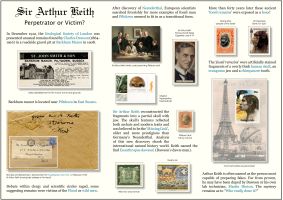

One slide presentation "Sir Arthur Keith perpetrator or victim", creatd by Mr. Fran Adams from USA

|

That summer, Dawson and Smith Woodward purportedly discovered more bones and artifacts at the site, which they connected to the same individual.

These finds included a jawbone, more skull fragments, a set of teeth, and primitive tools.

Smith Woodward reconstructed the skull fragments and hypothesised that they belonged to a human ancestor from 500,000 years ago.

The discovery was announced at a Geological Society meeting and was given the Latin name

Eoanthropus dawsoni ("Dawson's dawn-man").

The questionable significance of the assemblage remained the subject of considerable controversy until it was conclusively

exposed in 1953 as a forgery.

It was found to have consisted of the altered mandible and some teeth of an orangutan deliberately combined with the cranium of a fully developed,

though small-brained, modern human.

The Piltdown Man fraud significantly affected early research on human evolution.

Notably, it led scientists down a blind alley in the belief that the human brain expanded in size before the jaw adapted to new types of food.

Discoveries of

Australopithecine fossils such as the Taung Child found by Raymond Dart during the 1920s in South Africa were ignored

because of the support for Piltdown Man as "the missing link," and the reconstruction of human evolution was confused for decades.

Stephen Jay Gould, an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science, argued that nationalism and cultural

prejudice played a role in the ready acceptance of Piltdown Man as genuine, because it satisfied European expectations that the earliest

humans would be found in Eurasia, and the British in particular wanted a "first Briton" to set against fossil hominids found elsewhere in Europe.

Piltdown man, whose fossils were sufficiently convincing to generate a scholarly controversy lasting more than 40 years,

was one of the most successful hoaxes in the history of science.

Some naturalists who was searching for the fossils of prehistoric humans turned their attention to

Asia.

In 1918 Swedish geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson first started his explorations at an archaeological

site near the village of

Zhoukoudian, Beijing municipality in

China.

He was intrigued by tales of “dragon bones” that local people found in the clefts and used for medicinal purposes.

|

|

Postal stationery of China 2018 - "The Centenary of the discovery of Zhoukoudian site"

|

In 1921, Andersson and American palaeontologist Walter W. Granger were led to the site known

as Dragon Bone Hill by local quarry men.

During their exploration, Andersson discovered some quartz pieces that could have been used as early cutting tools.

This discovery lent credence to his theory that the bones were actually human fossils.

The excavation continued by Austrian palaeontologist Otto Zdansky in 1921 and 1923 unearthed two human teeth.

These were later identified by Canadian paleoanthropologist Davidson Black as belonging to a previously unknown species,

which he named

Sinanthropus pekinensis.

In 1929 the first skullcap was unearthed at the site by Chinese palaeontologist Pei Wenzhong.

So far, ancient hominid fossils, cultural remains, and animal fossils have been excavated from 23 localities

by international scientists in the

Zhoukoudian area.

These artefacts and remains date between 5 million and 10,000 years old.

These include the remains of

Homo erectus pekinensis, which are commonly known as the Peking man,

who lived during the Middle Pleistocene (700,000 to 200,000 years ago), archaic

Homo sapiens

from about 200,000–100,000 years ago and Homo sapiens sapiens dating back to 30,000 years ago.

At about the same time Andersson, Granger, and Zdansky were reporting new hominds excavated in China,

the first palaeoanthropological finds were being made in

Africa.

|

|

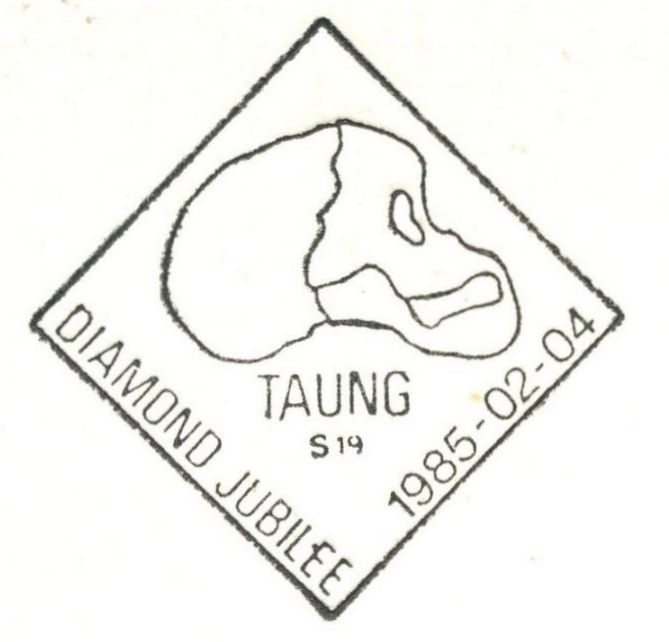

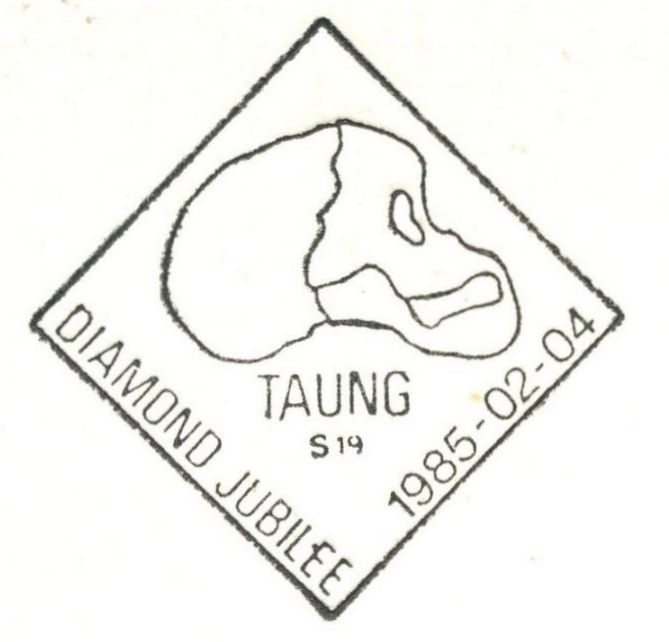

Taung skull on commemorative postmark of Bophuthatswana

|

|

|

|

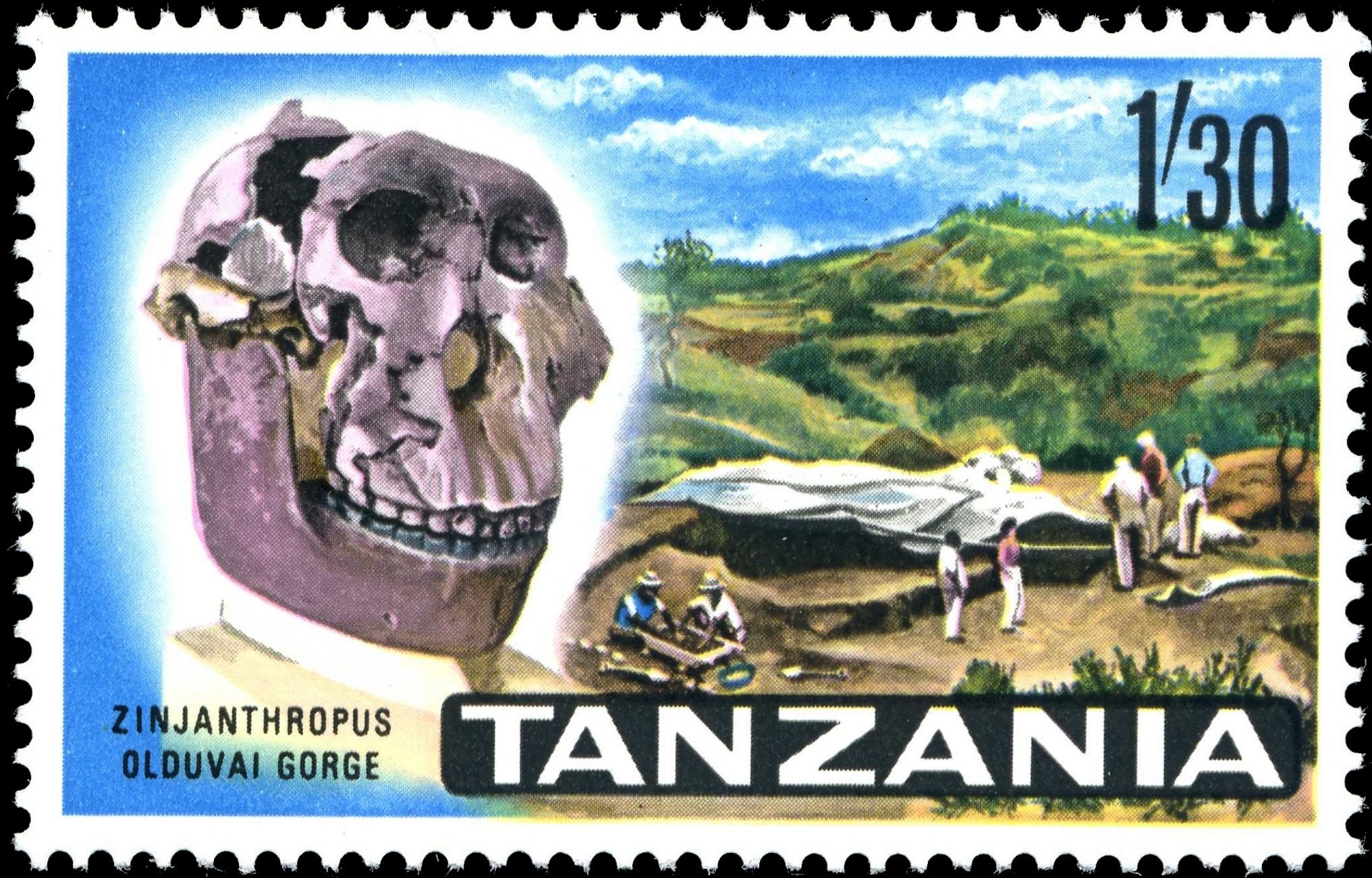

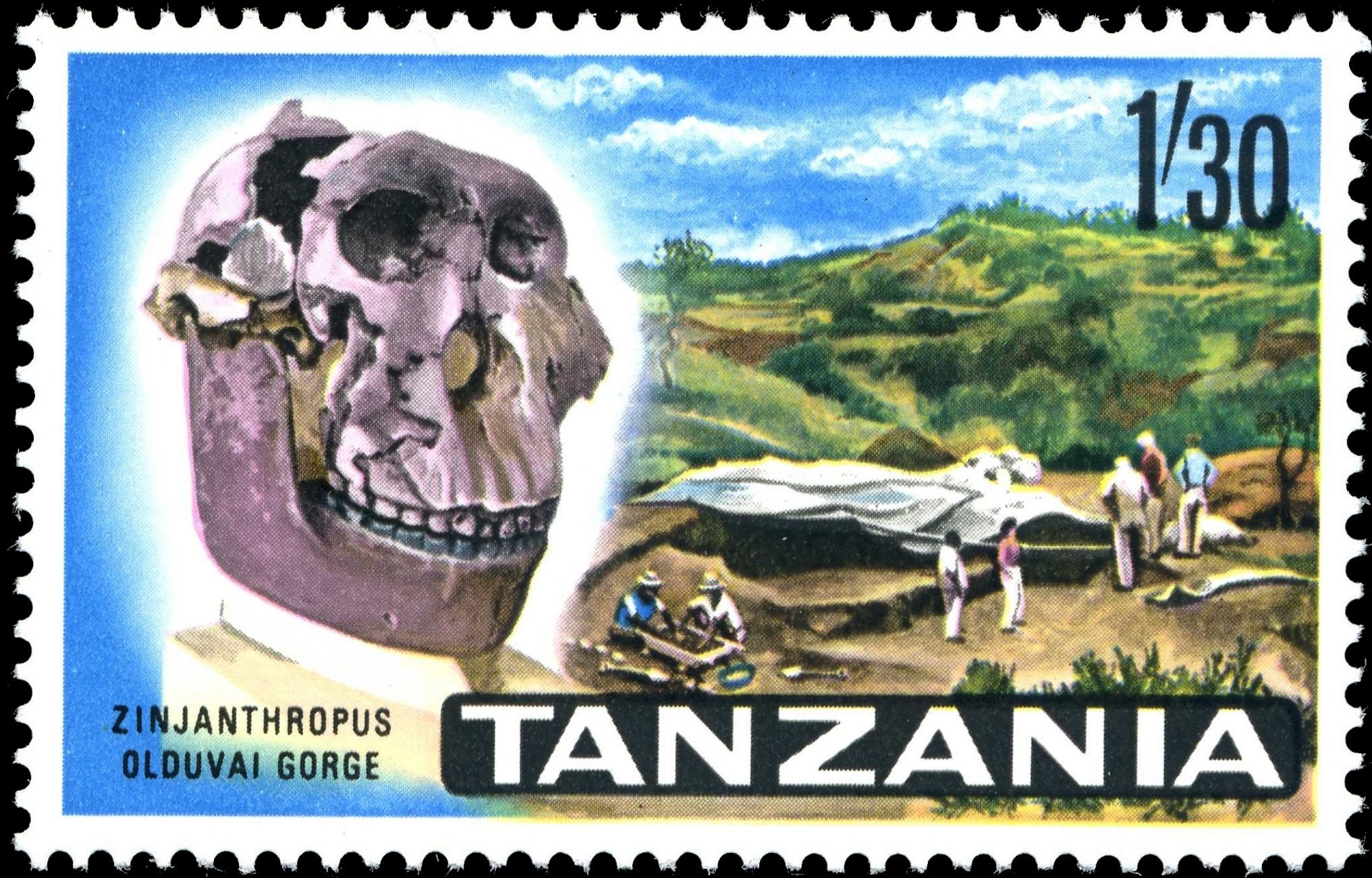

A skull of Zinjanthropus and group of paleoanthropologists on stamp of Tanzania 1965 MiNr.: 14, Scott: 14. |

In 1924 in a limestone quarry at Taung,

Professor Raymond Dart,

who was an Australian anatomist and anthropologist, discovered a remarkably well-preserved juvenile specimen

(face and brain endocast), which he named

Australopithecus africanus, also known as the

Taung Child.

In his report, published in 1925, Dart concluded that the Taung child was a bipedal human ancestor,

a transitional form between ape and human, who lived between 3.3 and 2.8 million years ago.

However, Dart's conclusions were largely ignored for decades, as the prevailing view of the time

was that a large brain evolved before bipedality.

In the 1930s, British- South African medical doctor and

palaeontologist Robert Broom discovered and described

a new species at Kromdraai,

South Africa.

Although similar in some ways to Dart's

Australopithecus africanus (2.27-0.87 million-year-old),

Broom's specimen had much larger cheek teeth.

Because of this difference, Broom named his specimen

Paranthropus robustus , using a new genus name.

Mary Leakey was a British paleoanthropologist

and wife of

Louis Leakey, a Kenyan-British Paleoanthropologist and archeologist.

In 1959, Mary Leakey discovered fossils of a hominid at the

Olduvai Gorge that she named

Zinjanthropus boisei.

Zinjanthropus boisei was later renamed

Paranthropus boisei.

This species of australopithecine lived during the Early Pleistocene between 2.5 and 1.15 million years ago.

Louis Leakey described her fossils a month after their discovery.

Both Leakeys were important proponents of the idea that humans evolved in Africa.

In the following year, the Leakeys discovered another unknown species of our ancestors, and assigned it to a new species,

Homo habilis - an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa

about 2.3 million years to 1.65 million years ago.

By the 1980s,

Homo habilis was proposed to be an ancestor of humans, directly evolving into

Homo erectus,

which evolved into modern humans.

This viewpoint is now debated.

In the late 1970s, Mary Leakey excavated the famous Laetoli footprints in Tanzania, which demonstrated the antiquity of

bipedality in the human lineage.

Today, the Olduvai Gorge valley in Tanzania is counted as one of the most important paleoanthropological sites in the world;

it has proven invaluable in furthering understanding of early human evolution.

It is often called the "

cradle of humankind".

This year is the 50

th anniversary of the discovery of “

Lucy”.

In 1974, fossils of the “Lucy” skeleton were excavated in

Ethiopia.

Lucy is a collection of several hundred pieces of fossilized bone comprising 40 percent of the skeleton of

a female of the hominin species

Australopithecus afarensis, dated to about 3.2 million years old.

|

|

Lucy skeleton on stamps of Ethiopia 1986

|

The skeleton is characterized by a small skull similar to that of non-hominin apes.

Paradoxically, it also has evidence of a walking-gait showing that the creature was bipedal and walked upright

- this is more akin to humans and other hominids.

This combination of primitive and advanced traits supports the hypothesis that bipedalism preceded the increase

in brain size during human evolution.

These bones were discovered by members of the International Afar Research Expedition at Hadar, a site in the Awash Valley

of the Afar Triangle in Ethiopia.

Lucy was named after the 1967 song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" by the Beatles, which was played loudly and repeatedly

in the expedition camp all evening after the excavation team's first day of work on the recovery site.

After public announcement of the discovery, Lucy captured much international interest, becoming a household name at the time.

In Ethiopia, Lucy is known as Dinqnesh meaning “you are wonderful”.

Lucy became famous worldwide, and the story of her discovery and reconstruction was published in a book by Johanson and Edey.

Beginning in 2007, the fossil reconstruction and associated artefacts were exhibited publicly in an extended six-year tour

of the United States; the exhibition was called “

Lucy's Legacy: The Hidden Treasures of Ethiopia”.

There was discussion of the risks of damage to the unique fossils, and other museums preferred to display casts of the fossils.

The original fossils were returned to Ethiopia in 2013, and subsequent exhibitions have used casts.

The casts were purchased by many Natural History Museums around the world.

In the 21

st century paleoanthropologists continue to make important discoveries, such as the discoveries of

Homo naledi.

In 2015, a team led by Professor Lee Berger announced a new species,

Homo naledi, based on fossils representing 15 individuals from the

Rising Star Cave system in

South Africa.

|

|

|

Official and personalized FDCs FDC signed by Professor Lee Berger.

Personalized FDC show reconstruction of Homo naledi on the cachet and Souvenir Sheet of South Africa 2017.

|

The story of Homo naledi started when two recreational cavers Steven Tucker and Rick Hunter entered a cave called Rising Star

(Naledi Chamber), eager to find an unknown channel and perhaps discover some fossils in an area commonly known as the ‘Cradle of Mankind’.

They took pictures in the cave and took them to Professor Lee Berger at the Department of Paleoanthropology at Wits University.

Dr. Berger advertised on Facebook for very thin people who had to be scientifically sound and have caving experience.

Six young women were selected out of almost sixty applicants from all over the world.

They went underground, gathered the fossils whilst filming and relayed images to Berger and his team who were above ground.

The bones were superbly preserved, and by March 2014, 1550 specimens in all, representing at least 15 individuals had been excavated;

these included even the tiny bones of the ear canal.

Parts of the skeletons looked astonishingly modern though other parts were quite primitive.

It was unclear how these fossils had made it into the cave. There was no sign that these hominids had fallen into the cave or had been

dragged there by animals or even floods.

There was also no evidence that they had lived in these caves.

The fact that

Homo naledi was not embedded in rock meant that dating the fossils became extremely difficult.

Homo naledi was originally thought to be approximately 2 million years old, but research published in 2017 dates the oldest specimen

of the species to be 335, 000 years old. The age of

Homo naledi suggests that the species may have lived alongside

Homo sapiens

Even though many mysteries in human evolution have been solved in the last 170 years, there are still many questions to be answered in the future.

Acknowledgements:

- Many thanks to fellow collector Mr. Peter Brandhuber from Germany for his support.

-

Many thanks to

Dr. Peter Voice from Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Western Michigan University, for reviewing the draft page .

References

- Paleoanthropology:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

New World Encyclopedia.

- Neanderthal:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Neanderthal Museum.

- Piltdown Man:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Natural History Museum UK in London,

PBS,

Science,

Science History Institue.

- Zhoukoudian Peking Man:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

UNESCO,

Beijin Info.

- Taung child (Australopithecus africanus):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Live Science.

- Paranthropus robustus:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

- Zinjanthropus boisei / Paranthropus boisei:

Wikipedia,

The Leakey Foundation,

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

- Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Natural History Museum UK in London,

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

- Homo naledi:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Natural History Museum UK in London,

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.