Thomas Jefferson the father of American Paleontology

Contents:

Introduction: who is Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) was an American Founding Father and the third President of

the United States from 1801 to 1809.

He was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence.

Jefferson was the nation's first U.S. secretary of state under George Washington and then

the nation's second Vice-President under John Adams.

|

|

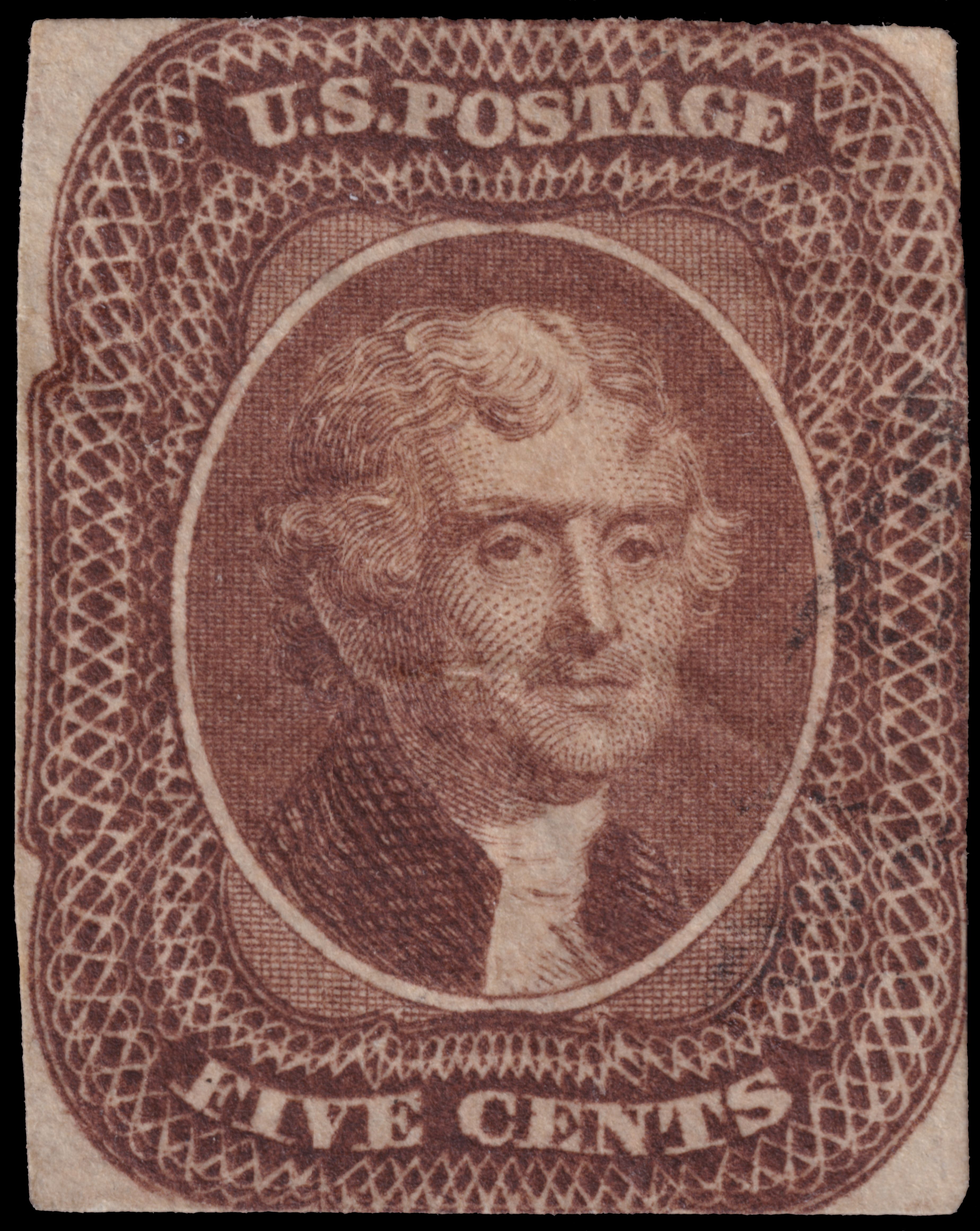

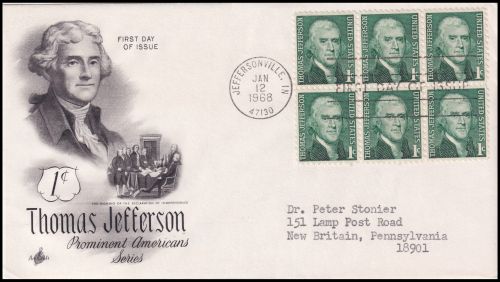

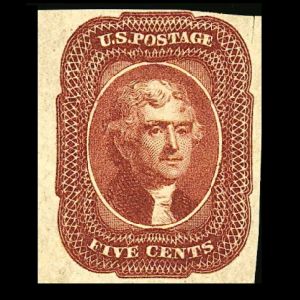

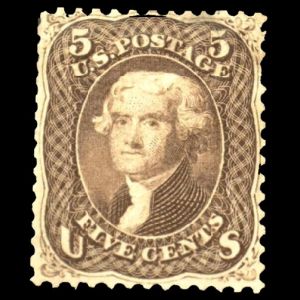

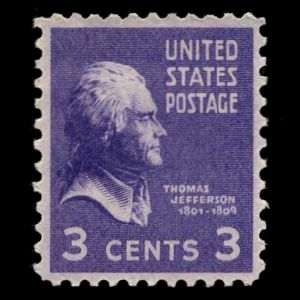

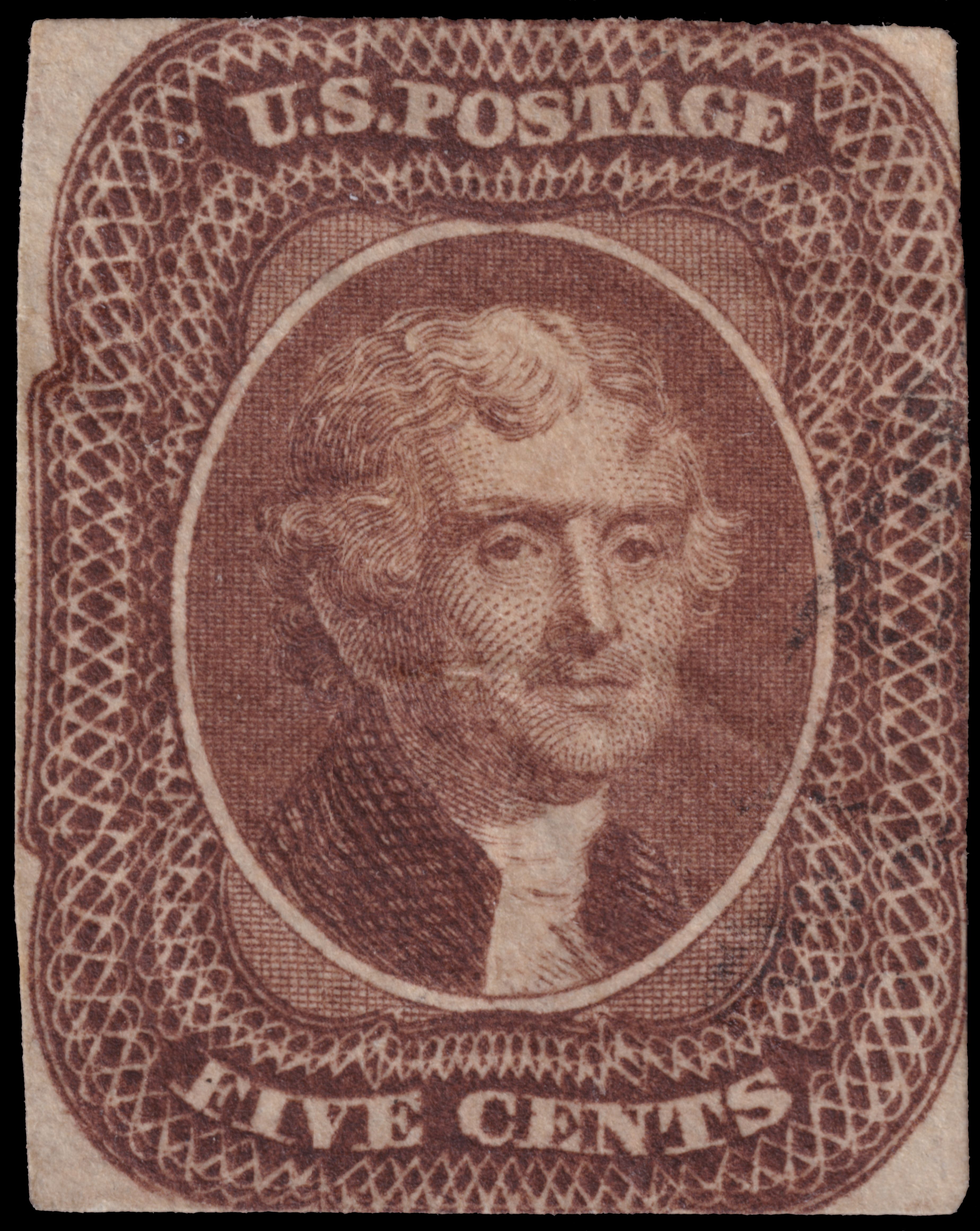

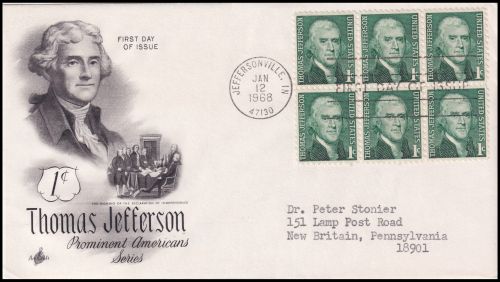

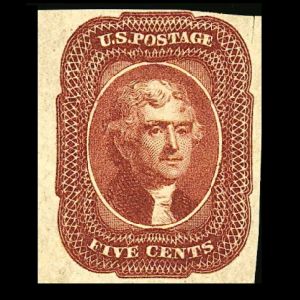

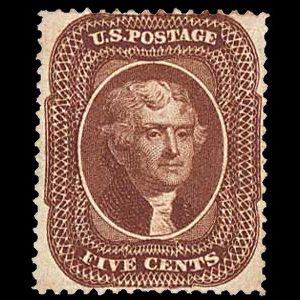

The first United States postage stamp depicting Thomas Jefferson was issued in 1856

as an imperforate 5-cent issue, MiNr.: 5, Scott: 12.

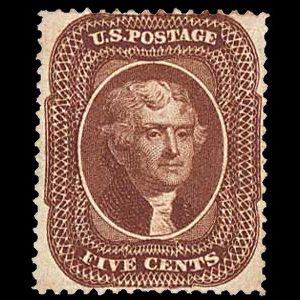

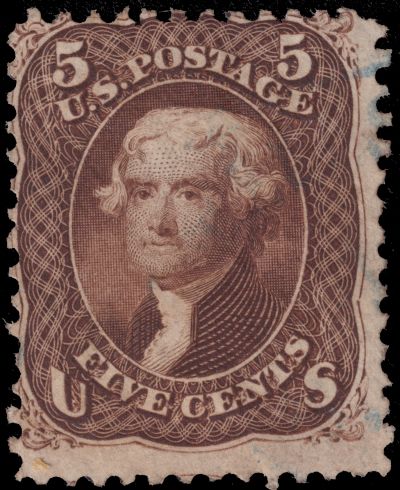

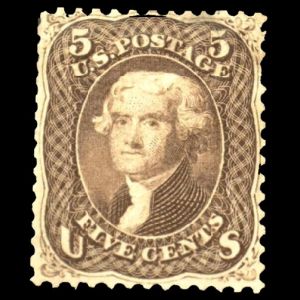

The same design was reissued perforated in 1857, then in 1862, it was

printed in mirrored orientation, MiNr.: 30, Scott: 15.

|

|

|

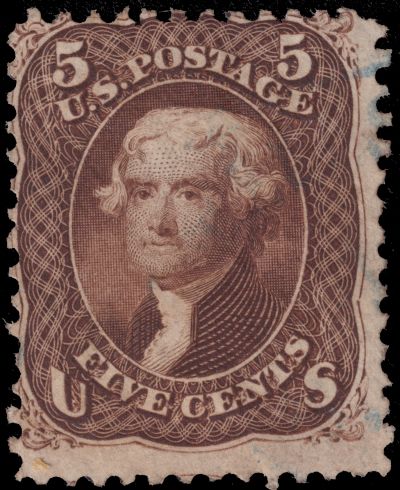

The cancelled stamp perforated on three sides with straight edge at top,

indicating position from the top row of the sheet.

The bold “X” is a contemporary pen cancellation, a common method used

by postmasters in the 1850s to prevent reuse of the stamp.

|

|

|

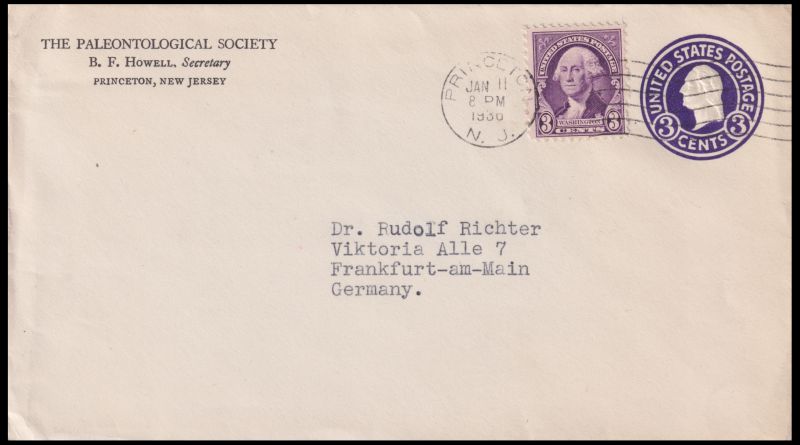

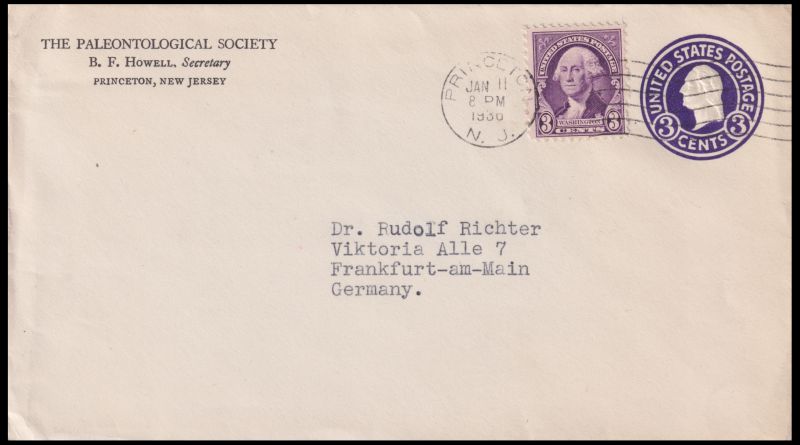

George Washington on imprinted and adhesive stamp on a letter sent from the Secretary of the Paleontological Society in 1936.

|

Jefferson was a leading proponent of democracy, republicanism, and natural rights,

and he produced formative documents and decisions at the state, national, and international levels.

Yet Jefferson was more than a statesman.

In his own time, he was widely respected as a serious and capable man of science.

His intellectual range was remarkable: a skilled mathematician and astronomer, he accurately calculated

the solar eclipse of 1778 and proposed refinements to almanacs concerning the equation of time.

He was knowledgeable in anatomy, civil engineering, mechanics, meteorology, architecture, and botany,

and he read and wrote Greek, Latin, French, Spanish, and Italian.

In addition to later contributions to ethnology, geography, and anthropology, Jefferson emerged as

a pioneering figure in early American palaeontology.

Despite this breadth of expertise, he modestly referred to himself as “an amateur” in science.

On April 29, 1962, President John F. Kennedy, at a White House dinner honoring American Nobel Prize winners,

famously remarked:

I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge,

that has ever been gathered together at the White House — with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson

dined alone.

|

|

|

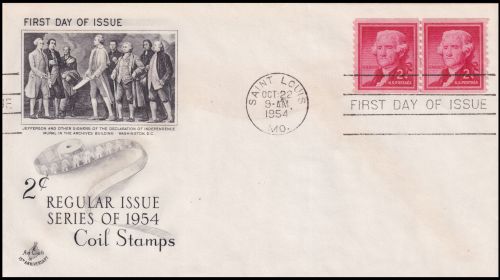

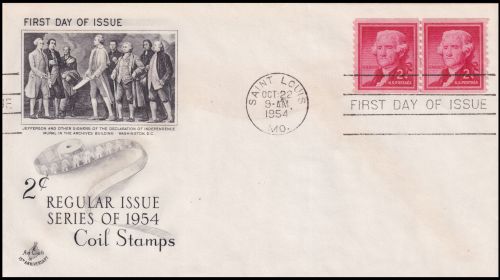

Thomas Jefferson and others signers of the Declaration of Independence

on FDC of USA from 1954 and 1968.

|

The Buffon Controversy (1760s–1780s)

|

|

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon on stamp of France 1949

MiNr.: 874, Scott: B241.

|

The origins of Jefferson’s palaeontological interests are closely tied to a transatlantic scientific debate.

In his monumental Histoire naturelle (published beginning in 1749), the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc,

Comte de Buffon, who never visited America,

argued that nature in the New World was inherently inferior to that of Europe.

In the 9

th volume of

Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière

he compared mammalian species and noted examples in which the same species lived on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean,

then claimed the New-World versions were always smaller and weaker,

that species common to both continents were diminished

in America, and that even humans were affected by climatic degeneration.

Buffon attributed this supposed inferiority to the moist, cold environment of the American continent.

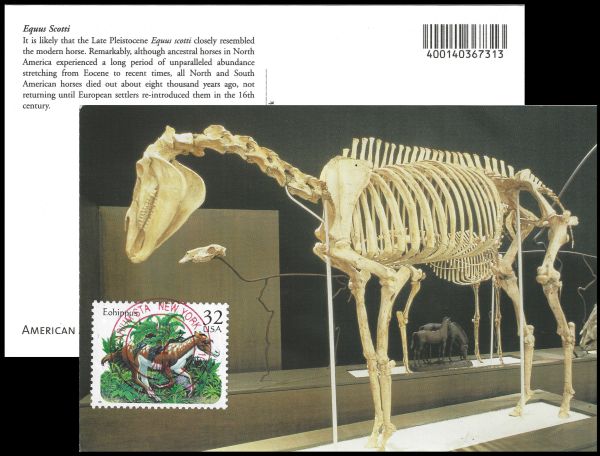

Buffon was not alone in promoting the idea of “degeneration” in the Americas.

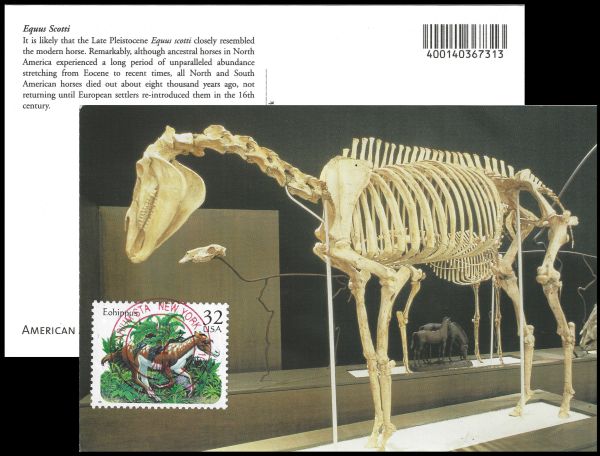

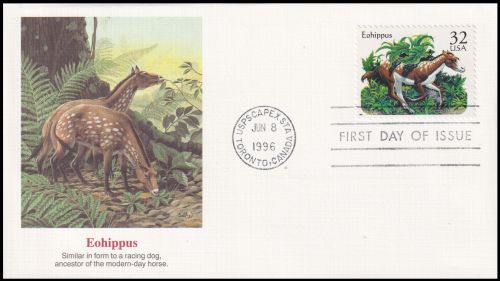

Several European observers circulated similar claims, suggesting that if European animals, such as horses,

were left to roam freely in the New World, they would quickly decline in strength or size.

Of course, Europeans did not realize that horses had been completely absent from the Americas for thousands of

years before their arrival — the animals they observed were newly reintroduced by colonists, making the degeneration

argument even more misleading.

Horses actually originated in North America millions of years ago, but they went extinct around 10,000 years ago.

When Europeans arrived, there were no horses in the Americas, the animals they brought were a reintroduction of

the species, not native populations.

This makes earlier European claims that horses “degenerate” in the New World even more misleading.

|

|

|

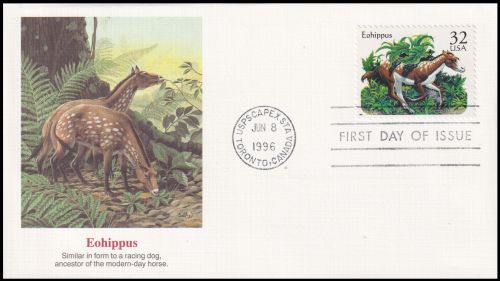

Prehistoric hourses Eohippus on a Maxi Card and FDC of USA 1996.

|

Jefferson regarded these claims as both scientifically flawed and politically insulting.

In 1785, while serving as American minister to France, he published Notes on the State of Virginia,

his most substantial scientific work.

In it, he systematically rebutted Buffon’s degeneracy theory, compiling measurements of American animals

— bear, deer, panther, and others demonstrating that many equaled or exceeded European species in size.

Collecting American Fauna and Expeditions

But Jefferson did not rely solely on printed argument.

Determined to provide physical proof, he began collecting large American animal specimens, both living and extinct.

He envisioned a systematic approach to document the continent’s fauna, seeking out the largest and most impressive

examples to counter Buffon’s claims.

|

|

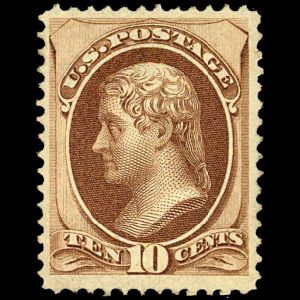

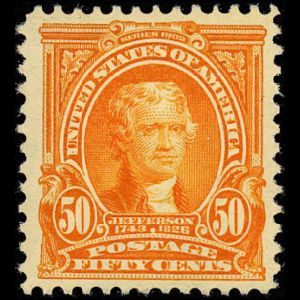

Thomas Jefferson on stamps of USA.

Above: 1904, MiNr.: 155, Scott: 324.

Below: 1954 with perforation error,

MiNr.: 654C, Scott: 1055.

|

|

In pursuit of this goal, Jefferson became a driving force behind several expeditions.

Most famously, he commissioned Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s Corps of Discovery (1804–1806) to explore the

newly acquired Louisiana Territory.

While the expedition is often celebrated for mapping the West and establishing relations with Indigenous nations,

Jefferson also tasked them with documenting North America’s wildlife in meticulous detail.

Lewis and Clark collected specimens, made detailed drawings, and recorded measurements of animals both familiar and

unknown to European science.

Jefferson also organized local expeditions closer to Virginia and the broader eastern seaboard, collaborating with

naturalists, hunters, and local residents to obtain specimens of large mammals, including bears, deer, elk, and the

elusive moose.

In the case of extinct animals, Jefferson corresponded extensively with explorers and fossil collectors,

sending instructions to collect fossils of giant extinct animals.

He meticulously measured, sketched, and preserved these specimens, often personally overseeing their preparation for

transport to his home and later to scientific institutions.

Through these combined efforts — field expeditions, specimen collection, and careful documentation —

Jefferson sought to demonstrate that North America was home to animals as large, strong,

and remarkable as any in Europe, providing tangible evidence to rebut the notion of New World “degeneration”.

While in Paris (1785–1789), as the United States ambassador to France,

he arranged for the shipment of a complete moose skeleton and skin to Buffon.

The specimen was enormous, reportedly requiring significant effort to transport across the Atlantic.

When Buffon, who never visited America, examined the moose, he conceded that at least some of his claims about

American animal size were mistaken, and later editions of Histoire naturelle softened aspects of his degeneracy thesis.

This scientific exchange — part publication, part material demonstration — marked one of the earliest international

debates in American natural history.

Interest in Fossils and the “Mammoth” (1780s–1790s)

While defending the vitality of American fauna, Jefferson became fascinated not only with living animals

but also with fossil remains, particularly the enormous bones commonly called “mammoth” bones.

These fossils, often found in the Ohio Valley and especially at Big Bone Lick in Kentucky, were widely discussed

in scientific circles.

At the time, it was unclear whether these bones belonged to elephants, unknown species, or animals still living

in the unexplored American West.

Jefferson refused to believe that any species could become extinct.

He wrote:

Such is the economy of nature, that in no instance can be produced her having permitted any one race of her animals

to become extinct.

This conviction shaped his interpretation of fossil discoveries.

Rather than seeing the bones as evidence of extinction, Jefferson speculated that living herds of “mammoths”

might still roam the western territories beyond the Mississippi.

He actively sought fossil specimens, carefully cataloguing them when received.

Many were sent to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia for study,

while others he retained for his personal collection at Monticello.

|

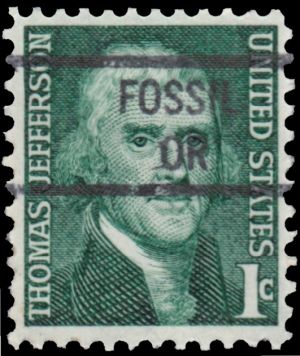

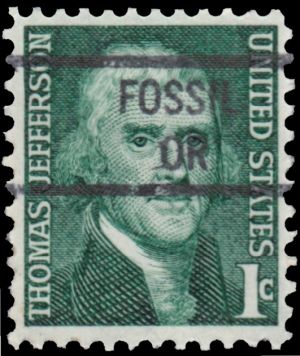

Thomas Jefferson stamp of USA 1968 with cancellation of "Fossil Or[egon]".

MiNr.: 940, Scott: 1278.

The name of Fossil in Oregon, United States, was chosen by the first postmaster,

Thomas B. Hoover, who had found fossil remains on his ranch.

The Fossil post office was established on February 28, 1876. As of the 2020 census,

Fossil had a population of 447.

|

|

|

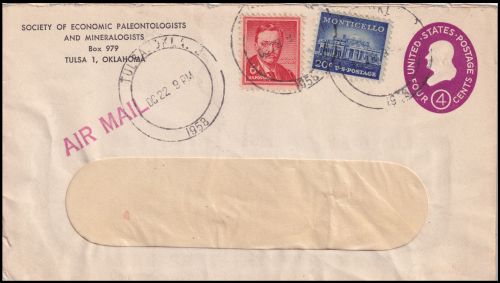

Stamp Monticello on a cover of USA 1956,

MiNr.: 669, Scott: 1047 on cover of Society of Economic Paleontologists

and Mineralogists from Oklahoma, posted in 1958.

|

Jefferson transformed the entrance hall of Monticello into a natural history gallery.

Fossils, antlers, horns, Native American artifacts from the Lewis and Clark expedition,

and scientific curiosities filled the space.

By assembling the fossil bones he collected personally at Monticello, Jefferson created more

than a private collection.

He built a bridge between legend, empirical observation, and scientific argument,

using these specimens to demonstrate the ancient history of life in North America and to challenge

European misconceptions about the continent’s natural richness.

Jefferson was particularly proud of this collection and considered it the centerpiece of

his natural history holdings.

When George Ticknor visited in 1815, he described seeing the head of a mammoth,

what Cuvier called a mastodon—displayed prominently.

These remains, likely from Big Bone Lick, symbolized Jefferson’s intellectual battle over

the vitality of American nature.

The majority of the bones he collected were eventually sent to the American Philosophical Society

in Philadelphia, while Monticello retained a carefully curated selection.

Jefferson’s interest in fossils was also sparked by Indigenous oral traditions that spoke of great beings and ancient

creatures revealed in the landscape.

Native communities used their own terms and concepts — such as spirits or ancestral giants like the Lakota Unktehi,

the Seneca Genonsgwa, and references to colossal “grandfathers” of familiar animals — to describe remains that

Europeans found puzzling.

European naturalists often interpreted these accounts through familiar reference points, translating them into terms

like “giant elephants” or “hairy giants,” even though such animals were unknown in Indigenous histories.

Jefferson approached these stories not as mere folklore, but as cultural clues pointing to the existence of extinct

species.

Motivated by both scientific curiosity and the desire to challenge European assumptions about the New World,

Jefferson organized and encouraged searches for fossil remains of these legendary creatures.

He personally corresponded with local farmers, explorers, and naturalists, urging them to report or collect any

large bones they found.

Through these networks, mastodon fossils began to surface across Virginia and neighboring states.

|

|

|

Mastodons on stamps of Marshall Islands 2009,

MiNr.: 2518, 2522; Scott: 956a, 956e.

|

Mastodons were large, elephant-like mammals with long, curved tusks and molars adapted for browsing trees and shrubs

rather than grazing.

They could grow up to 3 meters long and weigh around 6 tons — truly the “giants” of North America.

Jefferson meticulously measured, sketched, and documented each find, assembling a detailed record of these prehistoric

giants.

A particularly important discovery occurred in 1796 near Tuscaloosa, Alabama, when a large collection of mastodon bones

was uncovered along the Black Warrior River.

The find included a nearly complete skeleton, which local collectors carefully excavated and sent to Jefferson for study.

This discovery provided one of the first nearly intact mastodon skeletons in the United States and offered Jefferson

a remarkable opportunity to study the anatomy of an extinct American giant firsthand.

An even more dramatic episode unfolded in 1799 near Newburgh, New York, when laborers digging in a marl pit on

the farm of John Masten uncovered a massive femur.

Neighbors quickly joined the excavation, and a substantial collection of bones was gathered and stored in

Masten’s granary.

Reports of the discovery reached the American Philosophical Society and ultimately Jefferson.

Although deeply engaged in the contentious presidential election of 1800, Jefferson attempted to secure the bones

for scientific study.

|

|

|

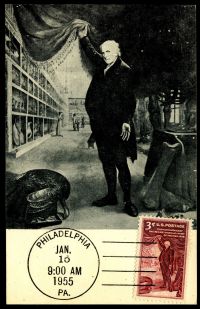

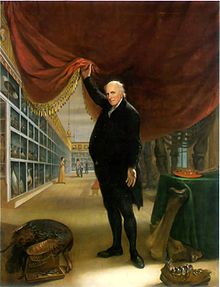

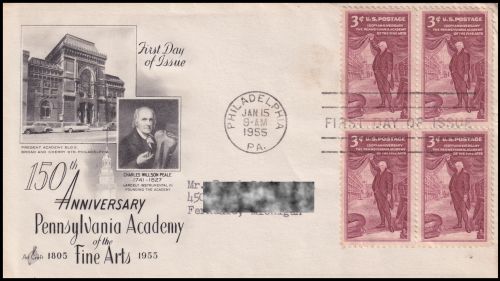

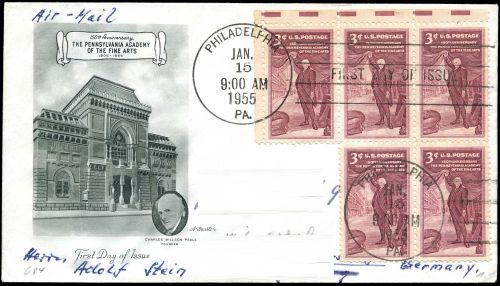

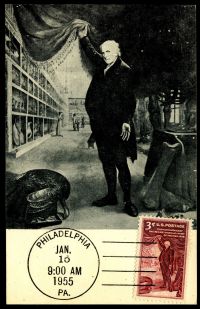

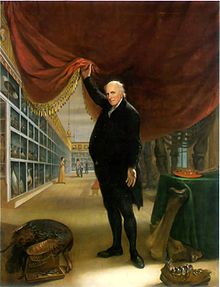

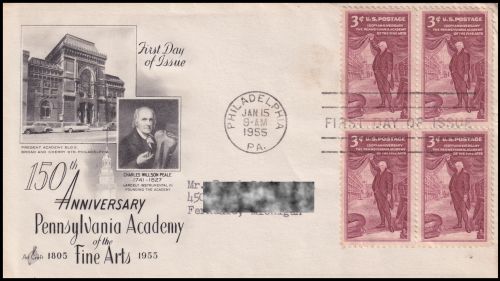

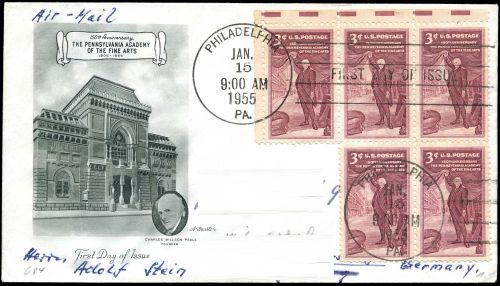

Charles Wilson Peale with mastodon bones in his museum, as depicted on a U.S. Maxi Card

and stamp (MiNr.: 684, Scott: 1064) from 1955 and in his painting

"The Artist in His Museum".

|

In 1801, the artist and naturalist

Charles Wilson Peale

purchased the recovered bones and organized further excavations.

Under the supervision of anatomist Caspar Wistar, Peale reconstructed the skeleton in Philadelphia,

replacing missing elements with wood or papier-mâché.

In December 1801, the mounted mastodon was unveiled before the American Philosophical Society and soon displayed

to the public in Peale’s museum.

The exhibition caused a sensation, and “mammoth fever” swept the young republic.

In February 1802, thirteen men,

including John Isaac Hawkins, father of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins who built

the first sculptures of prehistoric animals

in 1854 in London,

dined beneath the Peale mastodon at his Philadelphia museum.

The dinner was organized by Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale’s son.

After Charles Wilson Peale’s death in 1827, the museum declined, and much of its collection was sold.

The famous Peale mastodon skeleton was eventually purchased by the German naturalist Johann Jakob Kaup in the 1850s

and became part of the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, Germany, where it still resides today.

|

|

|

Charles Wilson Peale with mastodon bones in his museum on FDCs of USA from 1955

|

In 1799, Thomas Jefferson formally introduced the name “Mastodon” in a paper published in the Transactions of

the American Philosophical Society.

Drawing on classical Greek, he combined mastos (“breast”) and odon (“tooth”) to describe the distinctive conical

projections on the animal’s molars, which he believed resembled breast-like forms.

These unusual teeth clearly distinguished the creature from modern elephants, whose grinding molars were structured

differently.

|

|

|

Mastodon teeth versus mammoth on stamps of Slovenia (2018) and Tunisia (1982),

MiNr. 1297 and 1034; Scott 1263 and 809F, respectively.

|

Mastodons were browsers - their teeth have cusps that help chop up branches and tough woody plants.

Mammoths and Elephants have broad, flatter teeth - for grinding up grass.

In his paper, Jefferson carefully compared the fossil teeth and bones with those of known species, arguing that they

represented a distinct and powerful North American animal.

Although he resisted the idea that such creatures were extinct, suggesting instead that living herds might still

roam the unexplored western territories, he emphasized that the fossils demonstrated the immense size and antiquity

of American fauna.

By presenting anatomical evidence within a formal scientific framework, Jefferson helped establish fossil study

as a legitimate field of inquiry in the young republic.

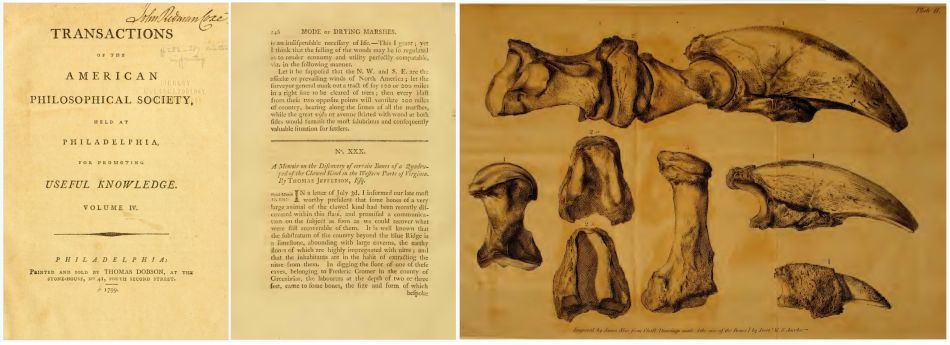

The Megalonyx Paper (1796–1799)

In 1796, Colonel John Stuart, a prominent Virginia figure, sent Jefferson large fossil

bones discovered in western Virginia (now West Virginia), from a cave in Greenbrier County.

Jefferson studied them closely, eager to learn more about North America’s prehistoric fauna.

In March 1797, shortly after becoming Vice President and upon being elected president of

the American Philosophical Society, Jefferson presented a paper titled:

A Memorial of the Discovery of Certain Bones of a Quadruped of the Clawed

Kind in the Western Part of Virginia

.

In this paper, Jefferson interpreted the fossils as belonging to a gigantic lion-like carnivore

and named the creature Megalonyx, meaning “giant claw,” in reference to its massive claws.

Using the anatomical account of the African lion by the French anatomist Daubenton for comparison,

Jefferson estimated that the Megalonyx weighed more than three times the weight of the lion.

This presentation is often considered the formal beginning of vertebrate paleontology in North America,

marking the first detailed description of a North American fossil mammal.

Notably, it is also the only formal scientific publication Jefferson ever wrote specifically on paleontology,

though he continued to study fossils extensively through correspondence, collections, and other writings.

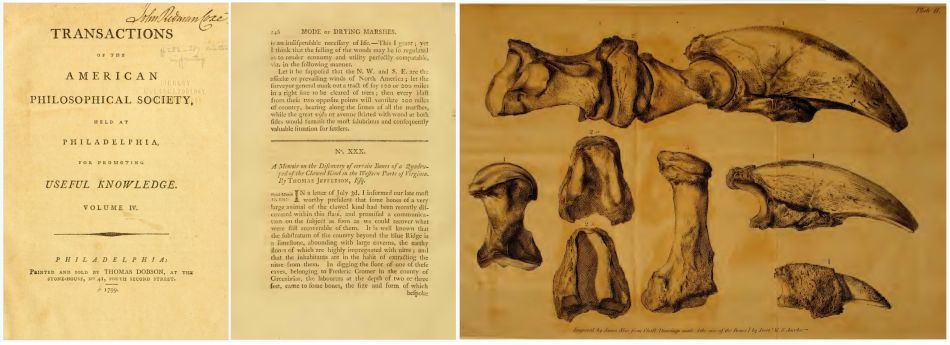

The work of Thomas Jefferson about the Megalonyx,

published in Transaction of the American Philosophical Society in 1799,

including the plate of the claw.

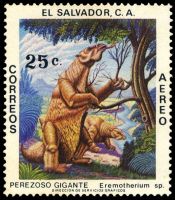

However, in 1799, anatomist Dr. Caspar Wistar correctly identified the bones as belonging to a giant ground sloth.

In 1802, the prominent French naturalist Georges Cuvier, often regarded as the father of paleontology,

examined casts of the fossils described by Thomas Jefferson that had been sent to Paris by Charles Willson Peale.

He confirmed that the claw and associated bones did not belong to a large carnivore, but instead to

the giant ground sloth

Megalonyx.

Cuvier explicitly compared

Megalonyx with the better-known prehistoric sloth from Argentina,

Megatherium, noting anatomical similarities that supported their close relationship among extinct ground sloths.

In 1822, Wistar proposed the species name

Megalonyx jeffersonii in Jefferson’s honor.

Megalonyx jeffersonii was a large herbivorous ground sloth that lived during the Pleistocene epoch.

Adults could reach up to 10 feet (about 3 meters) in length and had massive claws, likely used for pulling

down branches and for defense.

Despite Jefferson’s initial belief that it was a fearsome predator,

Megalonyx was a slow-moving browser

of forests and woodlands, an impressive example of North America’s Ice Age megafauna.

Today, the

Megalonyx bones described by Thomas Jefferson are preserved in the collections of

the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

They were transferred there in the mid-19th century by the American Philosophical Society after the Society withdrew

from maintaining natural history collections.

At a fossil site in Ecuador, at least 22 giant ground sloths (Eremotherium laurillardi)

were found preserved together. Scientists believe they gathered at a shallow waterhole,

and the buildup of feces and contaminated water may have caused disease or poisoning,

leading to their deaths.

This gives a rare glimpse into the risks faced by large herbivores in prehistoric ecosystems.

|

|

|

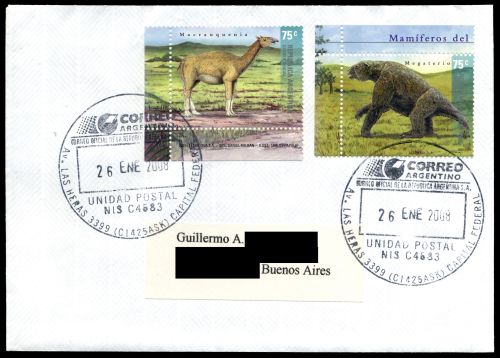

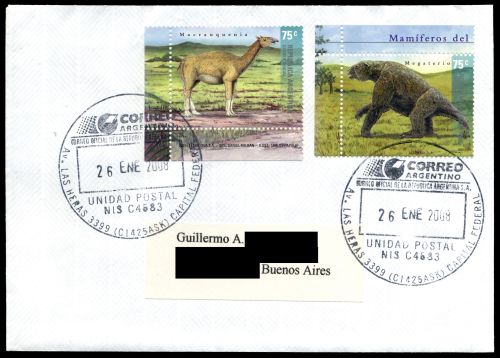

Georges Cuvier and Megatherium and FDC of France from 1969,

Megatherium's stamp from Argentina 2001 on a circulated cover posted in 2008.

|

Big Bone Lick and Western Exploration

|

|

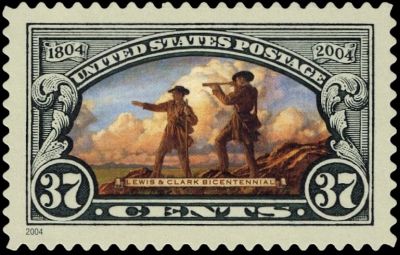

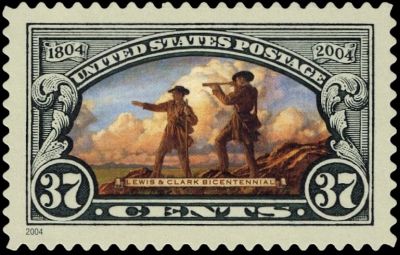

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on stamp of USA 2004

MiNr.: 3834, Scott: 3854.

|

The fossil site at Big Bone Lick, Kentucky, was the most famous source of large fossil

bones in North America.

Jefferson took a particular interest in this location.

After the Louisiana Purchase (1803) opened vast western territories, he saw exploration not only

as politically strategic but scientifically essential.

Jefferson instructed Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to collect information on geography,

flora, fauna and especially large animals.

He hoped evidence might confirm the continued existence of mastodons or mammoths in the West.

Later, he commissioned William Clark to investigate Big Bone Lick more thoroughly at his own expense.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, formally known as the Corps of Discovery,

was a United States mission to explore the newly acquired western territories

following the Louisiana Purchase.

The Corps consisted of a carefully selected team of U.S. Army personnel and civilian volunteers,

led by Captain Meriwether Lewis and his close friend, Second Lieutenant William Clark.

Numerous specimens from Big Bone Lick were sent to him. Most were forwarded to the American Philosophical Society,

but he kept select pieces for what he called “a special kind of Cabinet” at Monticello.

He regarded these fossils as prized elements of his natural history collection.

Public Criticism and the “Mastodon Room” (1808)

|

|

|

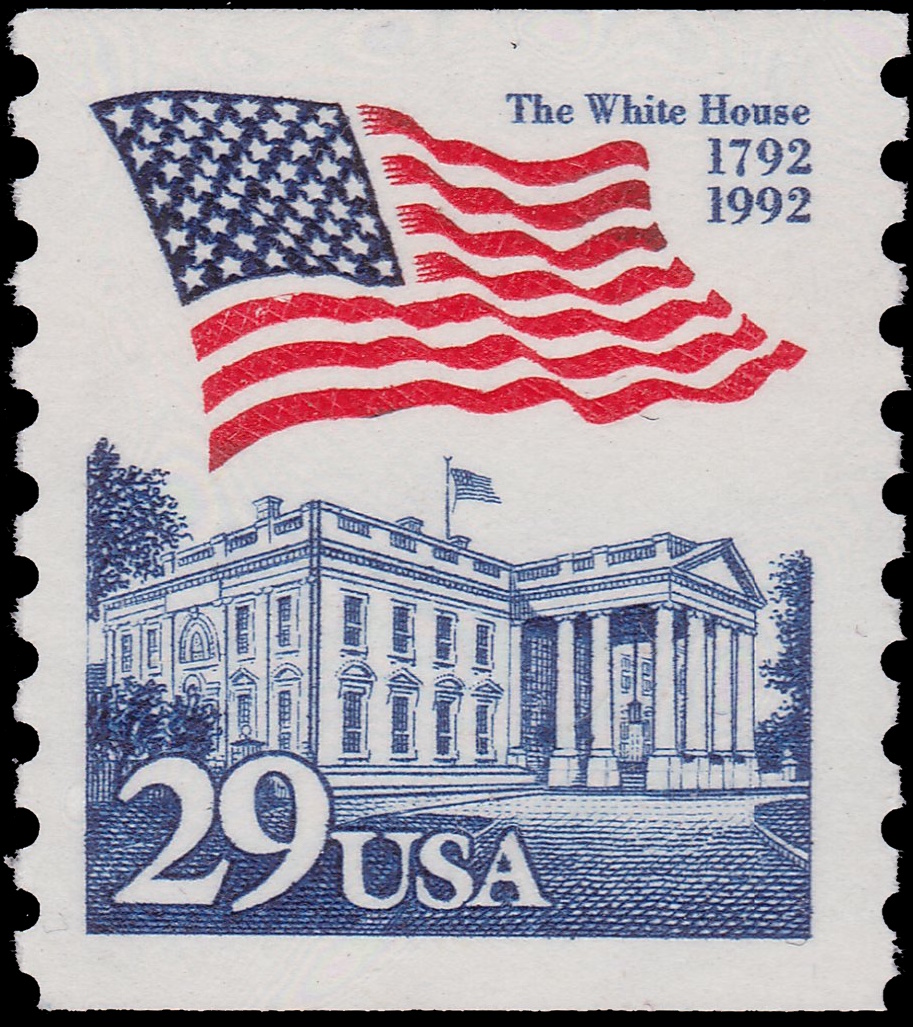

The White House on stamp of USA 1992

MiNr.: 2213, Scott: 2609.

|

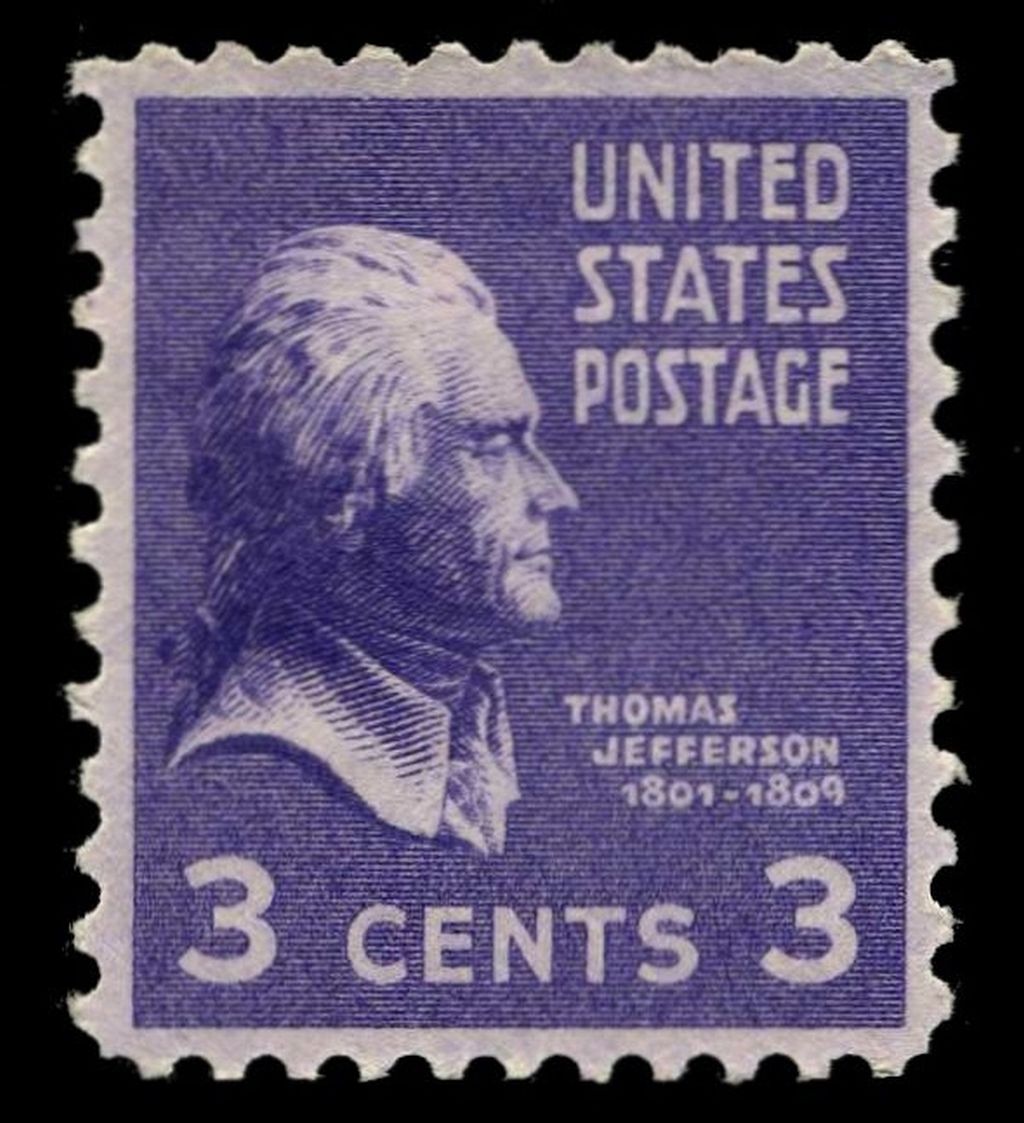

Thomas Jefferson on stamp of USA 1938

MiNr.: 414, Scott: 807.

|

Jefferson’s enthusiasm for fossils sometimes drew political criticism.

In 1808, amid controversy over the Embargo Act and worsening relations with Great Britain,

a wagonload of fossil bones was delivered to the White House.

Jefferson had them laid out in the unfinished East Room, which critics mockingly called

the “Bone Room” or “Mastodon Room.”

Opponents accused him of neglecting state affairs for scientific curiosities and derisively

nicknamed him “Mr. Mammoth.” Satirical poems mocked his fascination with fossil bones.

Legacy and Scientific Significance

Jefferson stood at a pivotal moment in the history of natural science.

His firm conviction that extinction was impossible placed him at odds with emerging European thinkers,

particularly Georges Cuvier, whose comparative anatomical studies were beginning to demonstrate

that entire species had vanished from the earth.

Yet Jefferson’s error was not born of ignorance, but of Enlightenment philosophy,

a belief in a rational and balanced natural order in which no species would be permanently lost.

Paradoxically, by promoting careful fossil collection, encouraging anatomical comparison,

and presenting the first formal scientific description of a North American fossil vertebrate,

he helped build the very scientific framework that would ultimately prove his own theory wrong.

|

|

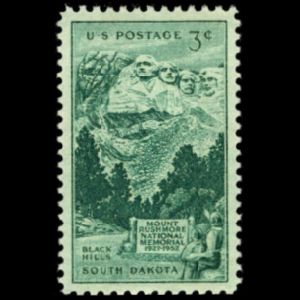

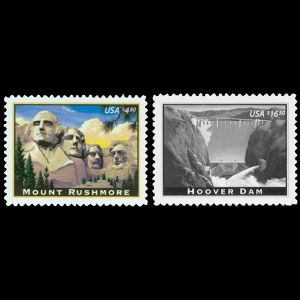

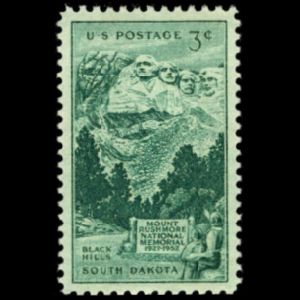

Mount Rushmore National Memorial on

"Plant for a more beautiful America" stamp of USA 1966

MiNr.: 909, Scott: 1318.

|

Paleontologists such as Frederic A. Lucas, then Curator‑in‑Chief of the U.S. National Museum,

and Henry Fairfield Osborn, at the time Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History,

described Jefferson as having founded American vertebrate paleontology and regarded him as the discipline’s

earliest guiding figure.

They crediting him with:

- Refuting Buffon’s degeneracy theory

- Encouraging systematic fossil collection

- Promoting stratigraphic awareness in excavation

- Presenting the first scientific paper on a North American fossil vertebrate

Today, Thomas Jefferson is often regarded as the father of American vertebrate paleontology.

Some argue that his refusal to accept extinction limits his scientific legacy.

Nevertheless, Jefferson’s greatest contribution may have been institutional and cultural.

As President, statesman, and leader of the American Philosophical Society, he lent prestige

and legitimacy to the study of fossils.

In a young republic still defining its intellectual identity, his public engagement with

natural history elevated palaeontology from curiosity to respectable scientific inquiry.

Through argument, collection, sponsorship of expeditions, and institutional leadership,

Jefferson helped lay the foundations of vertebrate palaeontology in North America.

|

|

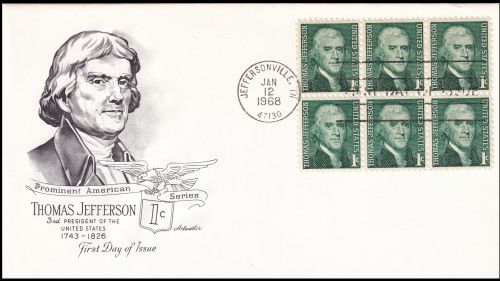

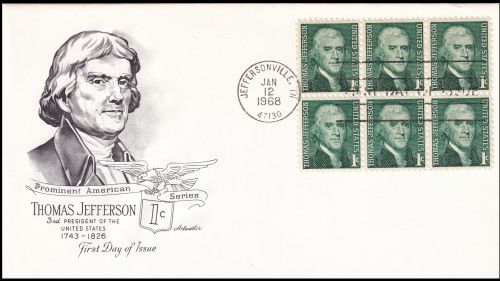

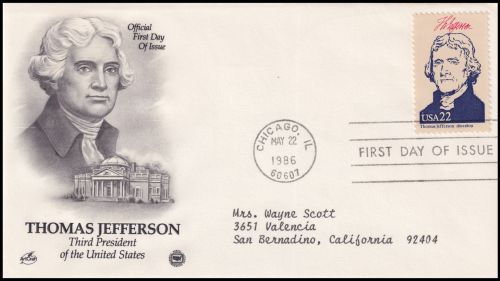

President Thomas Jefferson on FDC of USA 1968.

|

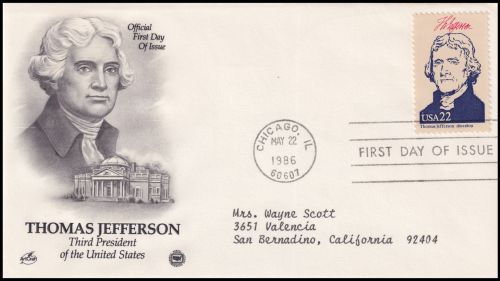

President Thomas Jefferson on FDC of USA 1986, with Monticello shown on the cachet beneath his portrait. |

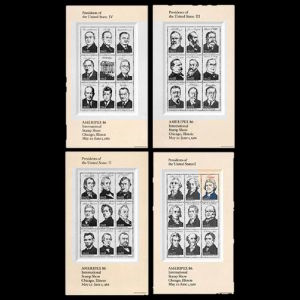

Thomas Jefferson in Philately

Many postage stamps and postmarks with Thomas Jefferson were issued

in the USA and other countries aroud the world.

Only stamps of Thomas Jefferson on a neutral background are listed below.

Other stamps, such as "Civil War" or "Declaration of Independence" are skipped as

irrelevant to the topic of Paleontology.

Stamps of the USA

Note:

- Stamp issue date of some old USA stamps are different in MICHEL and Scott catalogs.

In this case, the Scott Catalog dates are used in the table below.

| 14.031856 "Thomas Jefferson" |

1857 "Thomas Jefferson" |

19.08.1861 "Thomas Jefferson" |

|

|

|

|

| 13.03.1870 "Presidents" |

22.02.1890 "Presidents and other famous personalities", part of multi-year (1890-1893) definitive set |

01.01.1894 "Presidents and other famous personalities" |

|

|

|

|

| 23.03.1903 "Presidents and other famous personalities", part of multi-year (1902-1908) definitive set |

21.04.1904 "Louisiana Purchase Exposition" |

15.01.1923 "Personalities and Landscapes" |

|

|

|

|

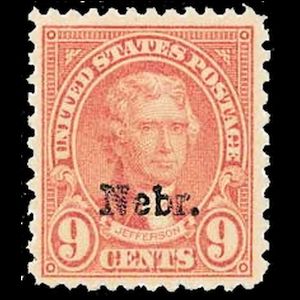

| 01.05.1929 "Personalities and Landscapes" |

16.06.1938 "Presidents of USA" |

15.09.1954 "Liberty issue" |

|

|

|

|

| 12.01.1968 "Famous Americans" |

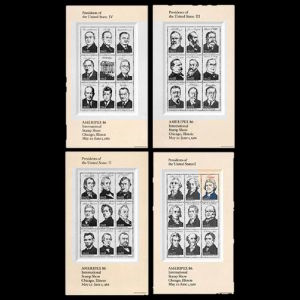

22.05.1986 "AMERIPEX'86, International Stamp Show - Presidents of the United States" |

03.04.1993 "Great Americans", part of big multi-year (1986-1994) definitive set |

|

|

|

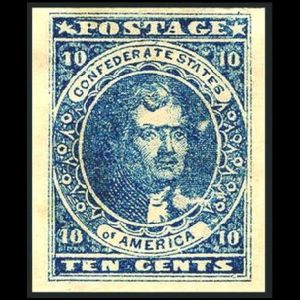

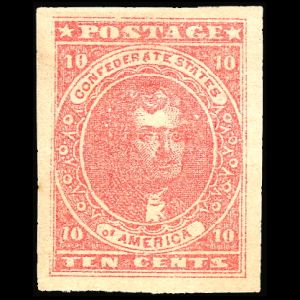

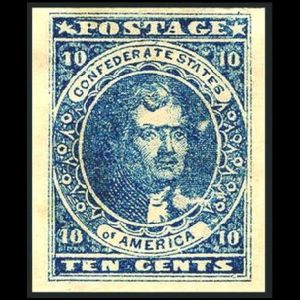

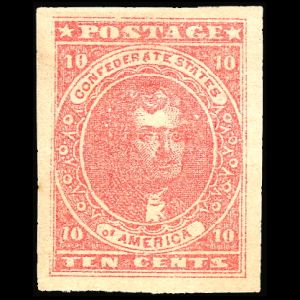

Confederate States of America (1861-1865), issued during Civil War

| 08.11.1861 definitive issue 1 |

25.07.1862 definitive issue 2 |

1862 reprint |

|

|

|

Some other stamps related to Thomas Jefferson:

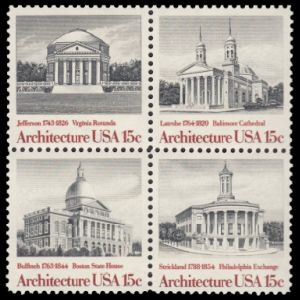

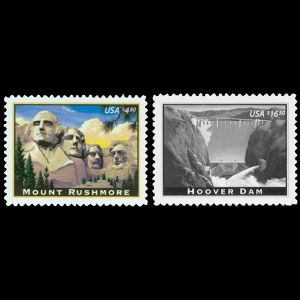

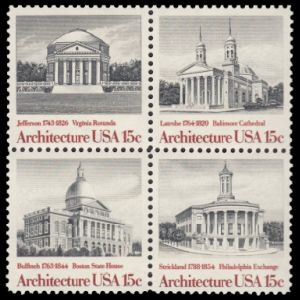

Mount Rushmore National Memorial, Jefferson Memorial, Virginia’s Rotunda, issued in USA.

-

Mount Rushmore National Memorial is a sculpture carved into the granite face of Mount Rushmore,

a granite batholith in the Black Hills in Keystone, South Dakota, United States.

Sculpted by Danish-American Gutzon Borglum and his son, Lincoln Borglum, Mount Rushmore features

60-foot (18 m) sculptures of the heads of four United States presidents,

including Thomas Jefferson.

-

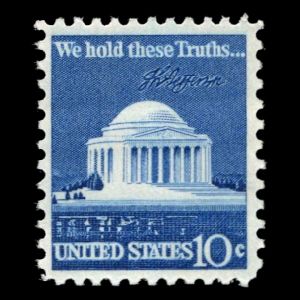

The Thomas Jefferson Memorial is a presidential memorial in Washington, D.C.,

dedicated to Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), built in Washington, D.C. between 1939

and 1943 under the sponsorship of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The bronze statue of Jefferson was added in 1947.

-

Virginia’s Rotunda - designed by the University’s founder, Thomas Jefferson,

the Rotunda is the centerpiece of the Academical Village.

Modeled after the Pantheon in Rome, it was designed to house the library and be flanked

on either side by faculty pavilions, interspersed with student rooms.

The University was established in 1819. Jefferson presented his plans for the Rotunda to

the Board of Visitors in 1821, and it was still under construction, plagued by delays and problems,

when Jefferson died in 1826.

| Mount Rushmore National Memorial |

| 11.08.1952 "25th anniversary of the dedication of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial" |

02.01.1974 "Mount Rushmore" (airmail) |

29.03.1991 "Flag over Mount Rushmore National Memorial" (coil stamp) |

|

|

|

|

| 06.06.2008 "American landmarks" (Priority and Express Mail) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

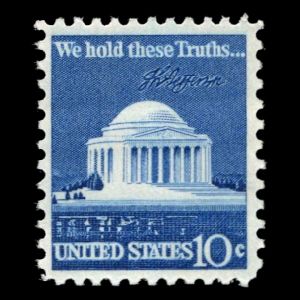

Jefferson memorial |

| 05.10.1966 "Beautification of America" (part of "Plant for a more beautiful America” campaign, initialized by President Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife.) |

14.12.1973 "Jefferson memorial and Signature"

(available with various perforation combinations. Scott 1510a-f) |

30.06.2002 "Jefferson memorial and Capitol Dome" (Priority and Express Mail, self-adhesive stamps) |

|

|

|

|

|

Virginia’s Rotunda |

| 04.06.1979 "American Architecture" |

|

|

|

|

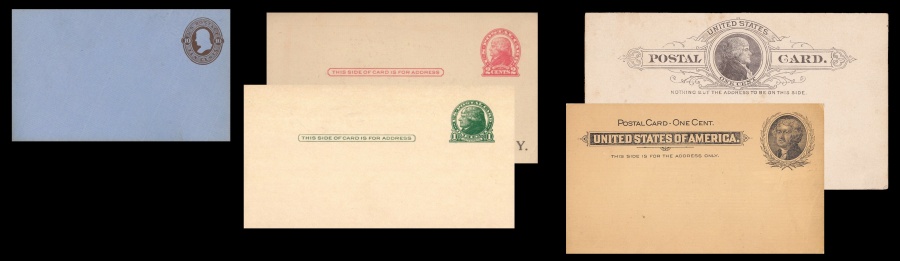

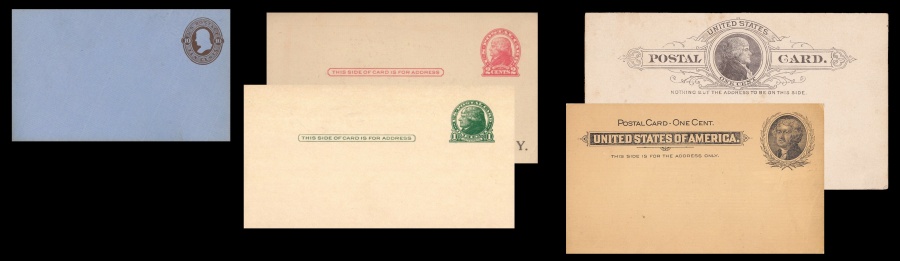

There are many postal stationeries with portraits and profiles of Thomas Jefferson

issued in USA in the second half of 1800s and beginning of 1900s

|

|

| Imrinted stamps from USA's postal stationeries related to Thomas Jefferson |

| USA, 18xx standart |

USA, 18xx standart |

USA, 1989 "Jefferson memorial" |

|

|

|

Commemorative postmarks and meter frankings of USA related to Thomas Jefferson

Legend is here

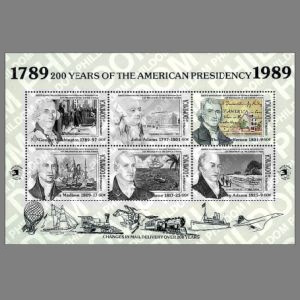

Some international postage stamps related to Thomas Jefferson

Undesired stamps are on the gray background.

| Andorra, 13.04.1973 |

Dominica, 17.11.1989 |

Ivory Coast, 27.11.1976 |

| "Thomas Jefferson, Presidential Birthplace Station" |

"200th anniversary of American presidency" |

"200th anniversary of American independence" |

|

|

|

|

| Romania, 25.01.1976 |

Seychelles, 21.12.1976 |

|

| "200th anniversary of American independence" |

"200th anniversary of American independence" |

|

|

|

|

References

|

-

Thomas Jefferson discussion with Comte de Buffon:

The Library of Congress ,

American Scientist,

Thomas Jefferson Foundation,

History News Network.

-

Thomas Jefferson - Paleontologist:

Varsity Tutors,

The Raab Collection.

-

Megalonyx Jeffersonii:

Thomas Jefferson Foundation,

Lewis & Clark Online,

Founders Online,

The Megalonyx, the Megatherium, and Thomas Jefferson's Lapse of Memory, by Julian P. Boyd.

Transactions of the American Philosophical Society vol. 4 (1799),

-

The Mastodon's fossil:

Lewis & Clark Online,

Smithsonian Magazie,

Chronogram Media ,

Patricia Hysell,

|