Postal Reform and Natural History during Queen Victoria's Reign

Content

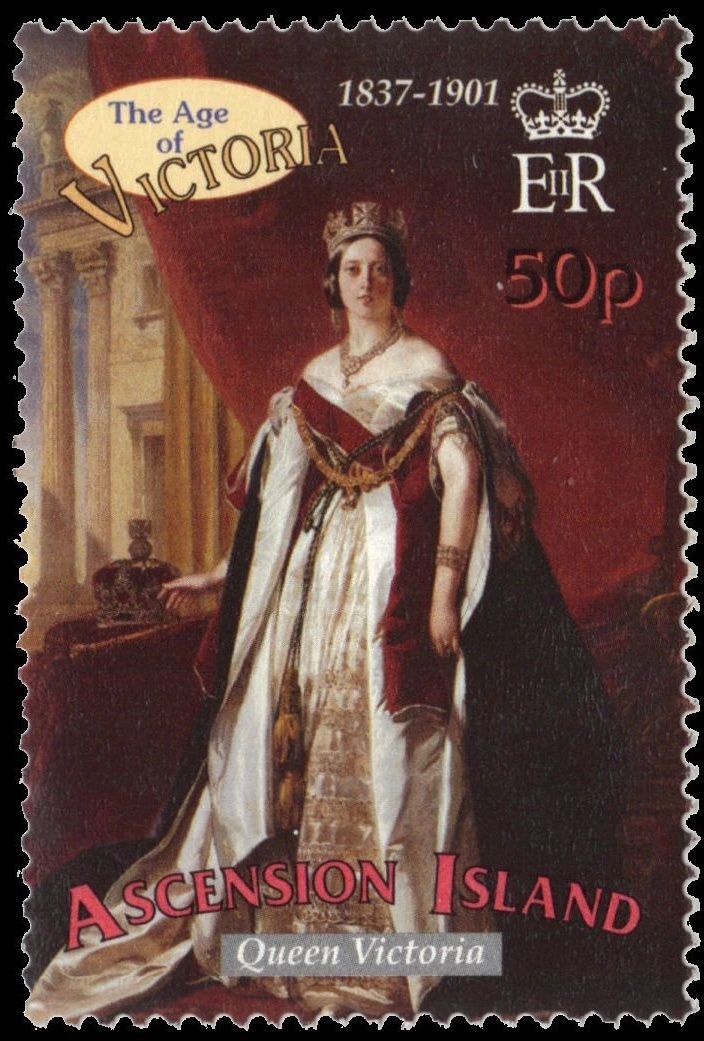

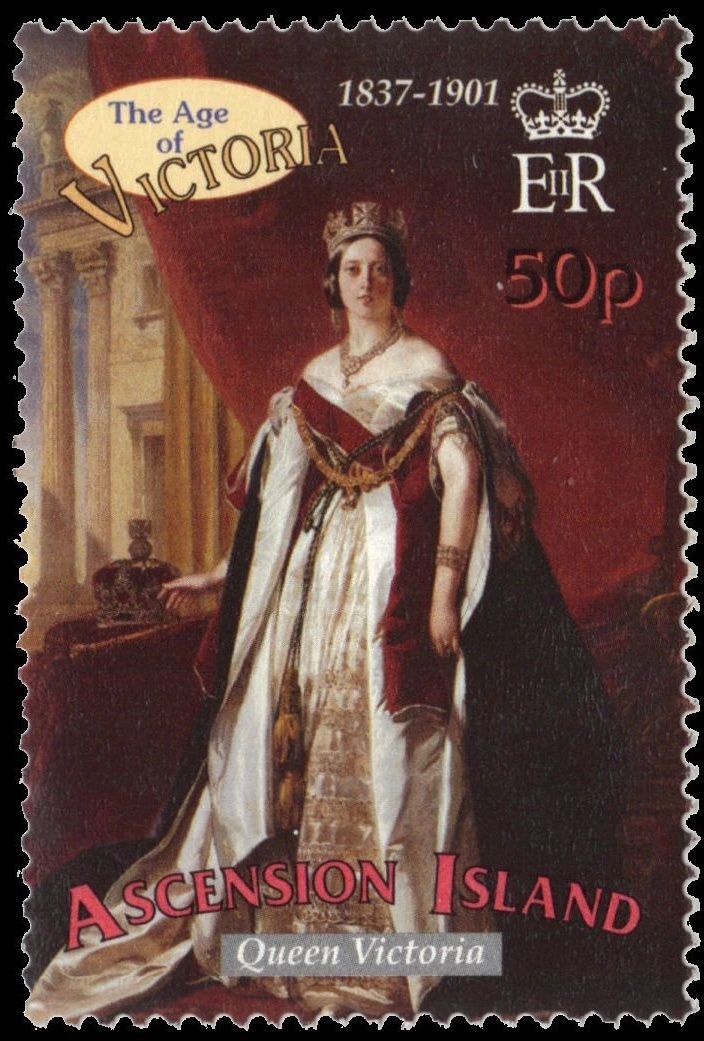

Queen Victoria (1819–1901) ascended the British throne in 1837 at just 18 years

old and reigned for 63 years, until 1901.

|

|

The wedding of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert on stamp of Great Britain 2019,

MiNr.: 4395, Scott: 3850.

|

|

|

|

|

The Penny Black and

the Two Pence Blue were

the first two postage stamp of the world - MiNr.: 1, 2; Scott: 1, 2.

|

Her reign quickly became synonymous with technological innovation,

cultural transformation, and the expansion of public knowledge.

This period is also often regarded as a golden age for museums in Britain.

Numerous metropolitan, provincial, and university institutions were established

or significantly expanded to house and display collections of art, natural history, science,

and antiquities.

Among the major museums whose development occurred during the Victorian era are

the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Natural History Museum in London.

In February 1840, she married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, whose strong interest in science,

education, and the arts helped define the intellectual tone of the early Victorian period.

Their partnership fostered a climate in which scientific progress, museum culture,

and modern communication systems flourished.

Postal Reform

One of the earliest major reforms implemented during Queen Victoria’s reign was

the Postal Reform.

Before this reform, Britain’s postal system was inefficient, expensive, and cumbersome.

Postage was charged according to the number of sheets and the distance travelled,

and letters were usually paid for by the recipient.

The reform, initiated by Rowland Hill with the support of Robert Wallace, member of Parliament,

and the Mercantile Committee on Postage in the mid-1830s, culminated in 1840 with the uniform postal rate,

the requirement to prepay postage, and the introduction of the world’s first adhesive postage stamp —

the Penny Black, featuring Victoria’s youthful profile.

This reform revolutionised communication across Britain and throughout the expanding empire.

It also played a crucial role in scientific exchange: naturalists, explorers,

and museum curators could now correspond more quickly and reliably, sharing letters, observations,

and specimens through the efficient postal networks that helped drive Victorian science.

The foundations of Geology and Paleontology

The same prerequisites that enabled the postal reform led to the foundations of modern geology.

As Britain began its transformation into an industrial power in the 1760s,

what is now known as

the British Industrial Revolution, the growing demand for iron, coal,

and other minerals elevated the importance of the mining industry.

This, in turn, created an urgent need for reliable information about mineral deposits and the natural

distribution of rock formations.

The deeper miners dug, the stranger the stones they extracted.

Some of stones were thought to be the “sports of nature”, but many were unmistakably

the fossilised bones and teeth of animals unlike any living species.

|

|

|

Gideon Mantell and William Buckland two scientists who described the

first three "giant reptiles", later grouped by Richard Owen to new genus -

"Dinosauria", on meter-franking of South Korea 2001 and 1995 respectively.

|

The first prehistoric reptiles,

Megalosaurus,

was described in 1824 by

William Buckland,

Professor of Geology at the University of Oxford and Dean of Christ Church.

Two more followed:

Iguanodon in 1825 and

Hylaeosaurus in 1833,

both described by the Sussex physician and amateur paleontologist

Gideon Mantell.

In 1841,

Richard Owen,

then Hunterian Professor of Comparative Anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons

and later superintendent the British Museum, recognised that these three reptiles formed a distinct natural group.

He named them

Dinosauria

, meaning “terrible lizards”, characterised by upright limbs and strongly built vertebrae.

The term

Dinosauria

was formally published in 1842 in Owen’s Report on British Fossil Reptiles,

prepared for

the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

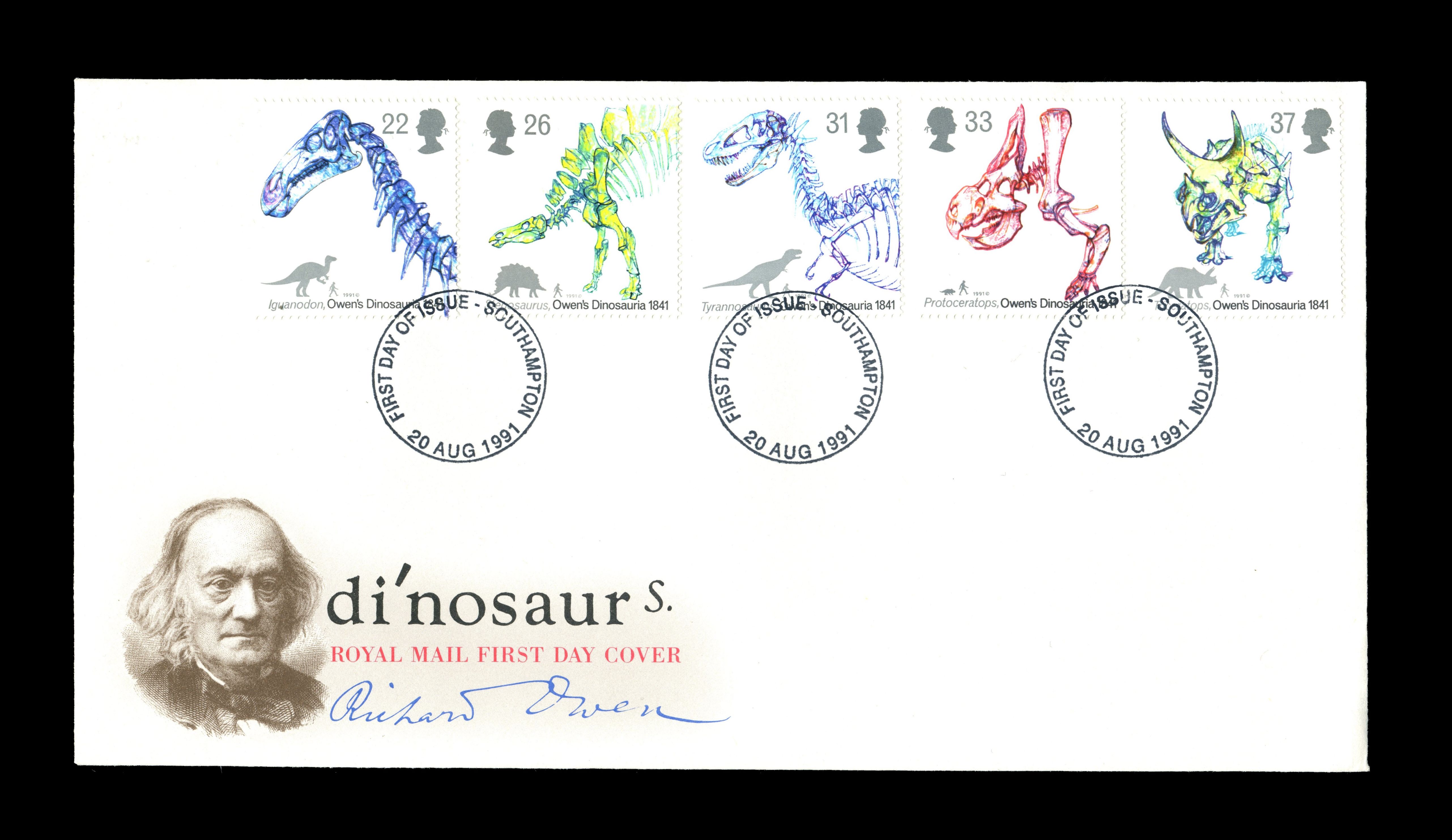

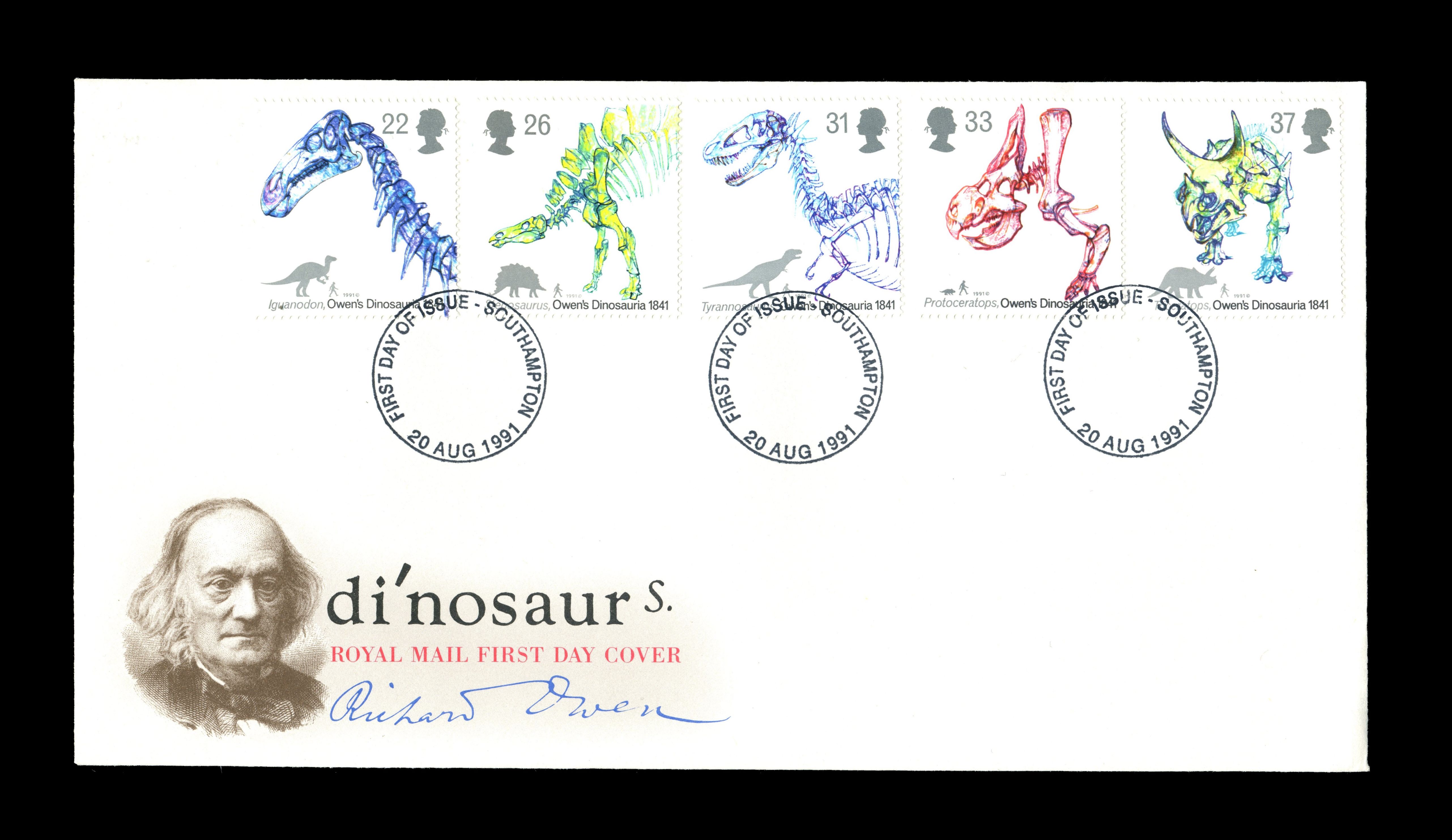

FDC with

150th Anniversary of Dinosaurs' Identification by Sir Richard Owens

stamps of Great Britain 1991

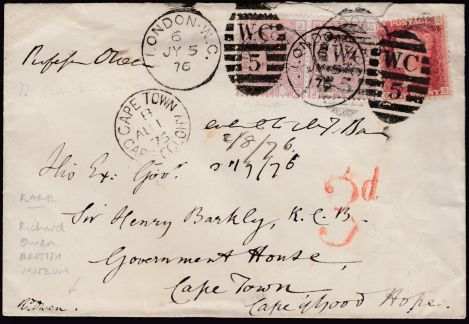

Owen was not an explorer, his work relied primarily on the extensive collections of

the Hunterian and the British Museums, where he worked between 1827-1856 and 1856-1883 respectively .

He also corresponded with officials and governors across the British colonies and explorers,

who assisted him in obtaining fossils and other specimens from remote parts of the British Empire.

For example

-

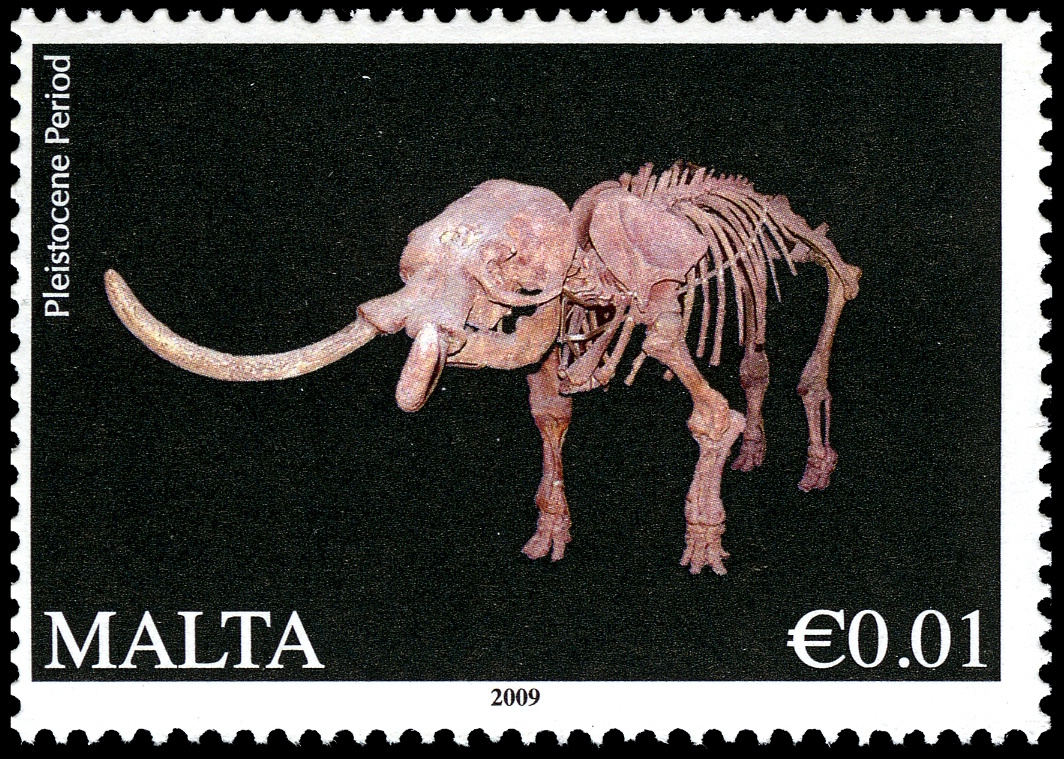

Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt (1811–1888), a Royal Navy officer and hydrographer,

explored caves in Malta, collecting Pleistocene mammal fossils,

including dwarf elephants (Palaeoloxodon falconeri).

His specimens were deposited in the British Museum (Natural History), forming part of

the Mediterranean fossil record.

-

Owen’s first major source of Australian fossils was Thomas Livingstone Mitchell (1792-1855),

the Surveyor General of New South Wales from 1828 to 1855.

Mitchell played a pivotal role in the earliest scientific discovery of

Australian megafauna.

During his 1830–1831 exploration of the Wellington Caves, he oversaw the excavation of

the distinctive red-earth breccia rich in Pleistocene vertebrate remains.

Mitchell sent these fossils, including bones of Diprotodon, Nototherium, giant kangaroos,

and other extinct marsupials, to London, where they were studied by Richard Owen.

In a series of papers from 1838 to 1842, Owen repeatedly credited Mitchell as the collector

and used his material to establish some of the first scientifically recognized species

of Australia’s extinct megafauna.

In recognition of their mutual respect, Mitchell named a peak in Queensland Mount Owen,

while Owen honoured Mitchell by giving the name Nototherium mitchelli to a large,

Diprotodon-like extinct marsupial.

-

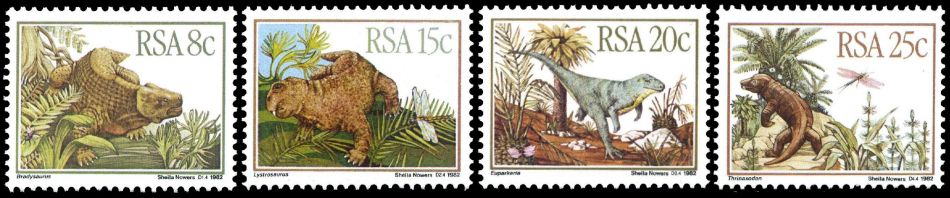

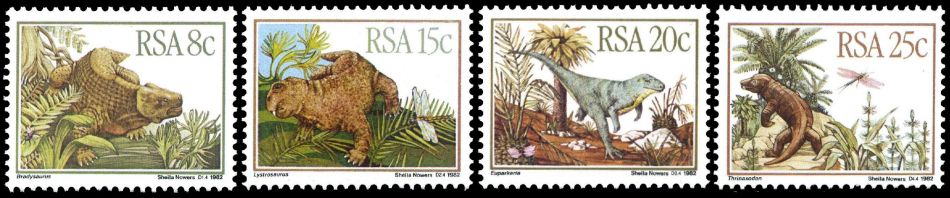

In southern Africa, Andrew Geddes Bain (1797–1864), renowned as the father of

South African geology, and his son

Thomas Charles John Bain,

collected numerous fossils from the Karoo region, including

reptilian and mammal-like forms.

They sent many of these specimens to Richard Owen, who described them in details, naming species

such as the dicynodont Oudenodon bainii in their honour

and analyzing the so-called “Blinkwater Monster”.

Mammal-like reptiles from Karoo formation on stamps of South Africa

Karoo Fossils

,

MiNr: 622-625, Scott: 606-609.

|

|

|

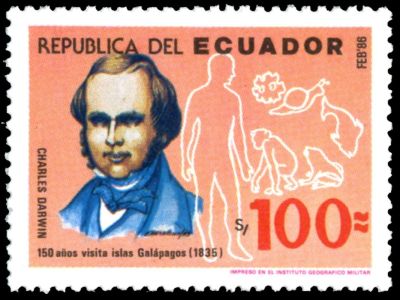

Megatherium on stamp of Argentina 2001,

and young Charles Darwin

on stamp of Ecuador 1986,

MiNr.: 2642,2023; Scott: 2144a, 1120 respectively.

|

|

|

|

Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their children on stamp of St Helena 2001,

based on the painting from 1846,

MiNr.: , Scott: .

The children were taught zoology and anatomy, including fossil studies,

by Professor Richard Owen, who is not shown on the stamp.

|

Postal reform made communication faster, cheaper, and more reliable, enabling

naturalists, such as Richard Owen to maintain close contact with many of the leading naturalists of his time.

These included

Georges Cuvier,

often regarded as the father of paleontology,

Charles Lyell, the proponent of uniformitarianism, and

Charles Darwin, who sent Owen fossil mammals collected

during the voyage of the

HMS Beagle,

including remains of

Megatherium, the giant ground sloth.

Through meticulous anatomical research, influential publications, and widely attended public lectures,

Owen brought prehistoric life to both scholarly and popular audiences, establishing himself as one of

the central figures of Victorian natural history.

His influence extended beyond research and museums into royal education:

Owen personally instructed Queen Victoria’s children in zoology, anatomy, and fossil studies,

reinforcing the monarchy’s symbolic association with science and promoting natural history as part of

elite cultural education.

Owen was also a driving force behind the expansion and reorganisation of Britain’s museum collections.

Spending nearly his entire career within museum institutions, he played a decisive role in shaping their development

and became the leading British naturalist in the decades preceding the publication of

Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species

(1859).

His central ambition was the creation of a separate museum of natural history, independent of the British Museum.

To build public and political support for this vision, Owen initiated a sustained programme of public lectures

from 1837 to 1864, delivered in London and regional centres such as

Ipswich.

These lectures, attended by prominent figures, including the young

Charles Darwin, who heard Owen’s comparative anatomy

lectures at the Royal College of Surgeons in 1837–1838, helped popularise natural science.

Owen also introduced guided tours of the Hunterian Museum, making its collections more accessible and engaging

to the general public.

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations

The first international “Expo,” officially titled

the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, was held between

May and October 1851 in the purpose-built Crystal Palace, the world’s first large building

constructed primarily of glass and iron.

Conceived as a celebration of modern industrial technology, design, and progress, the Exhibition was driven

by Prince Albert, who served as President of the Royal Commission, the body responsible for planning,

financing, and executing the event.

Among the key organizers was Henry Cole, who had previously collaborated with Rowland Hill on the design

and production of

the world’s first postage stamp.

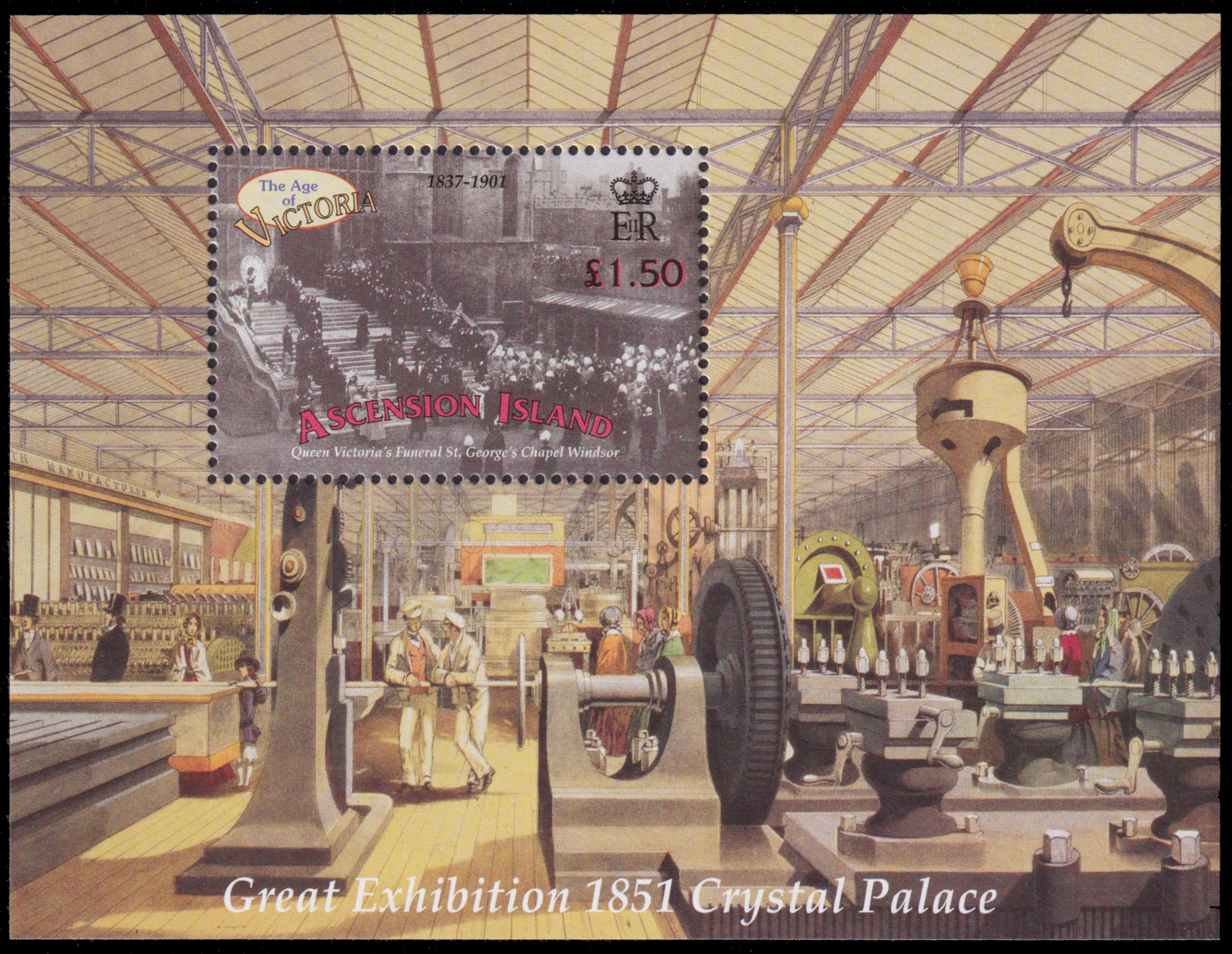

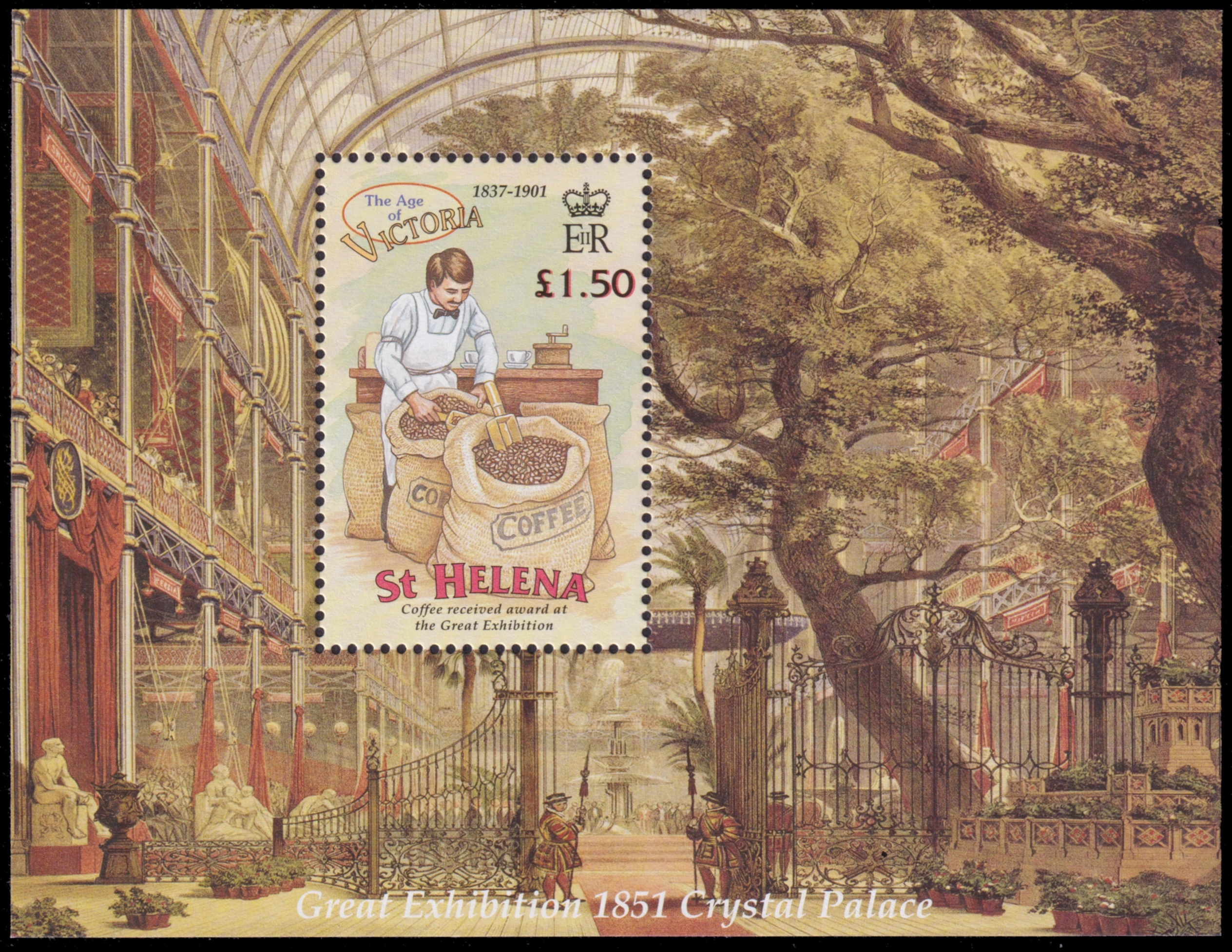

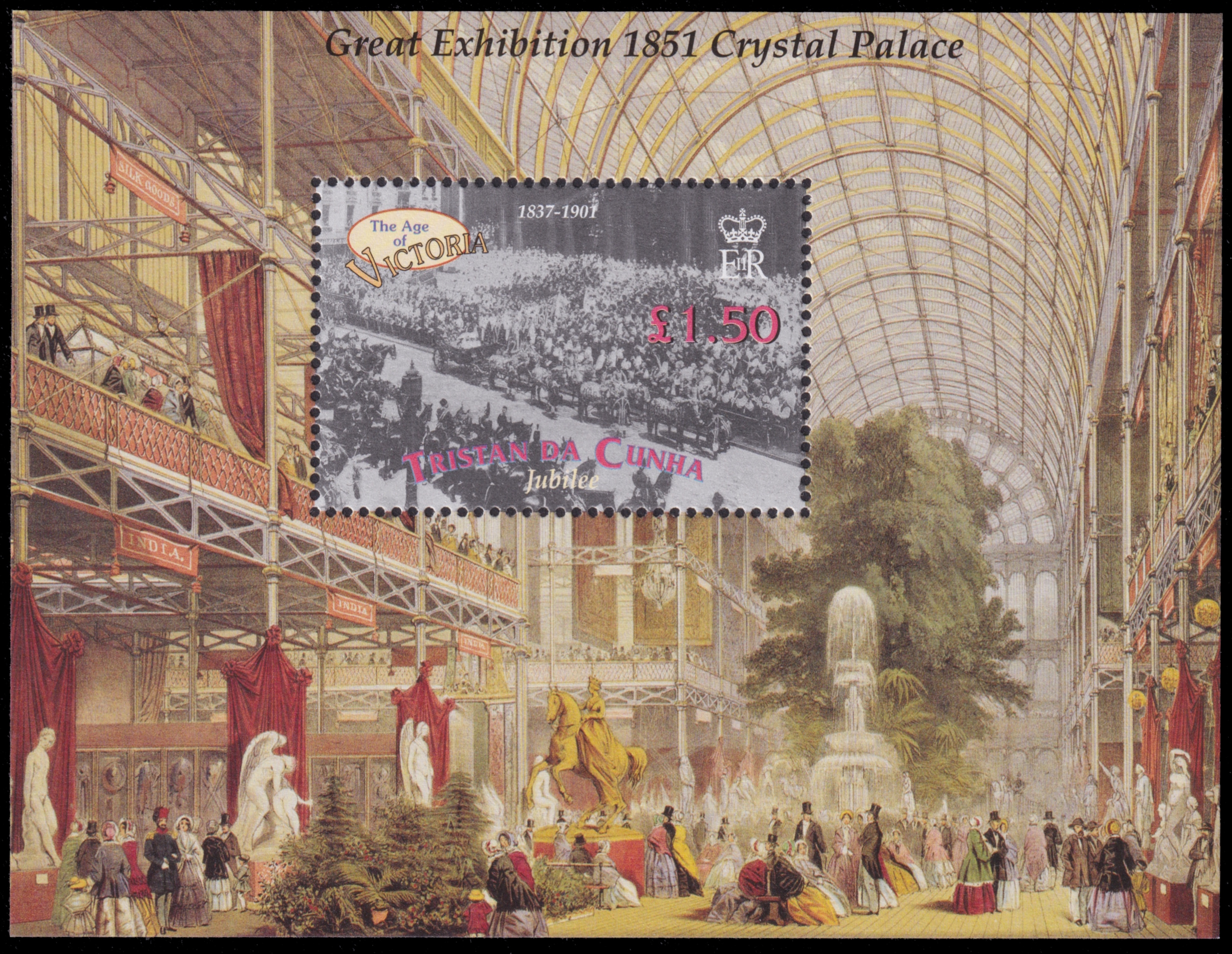

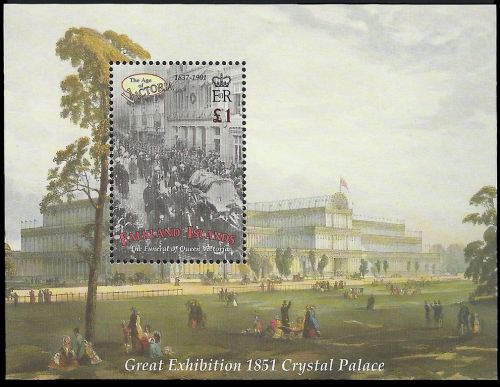

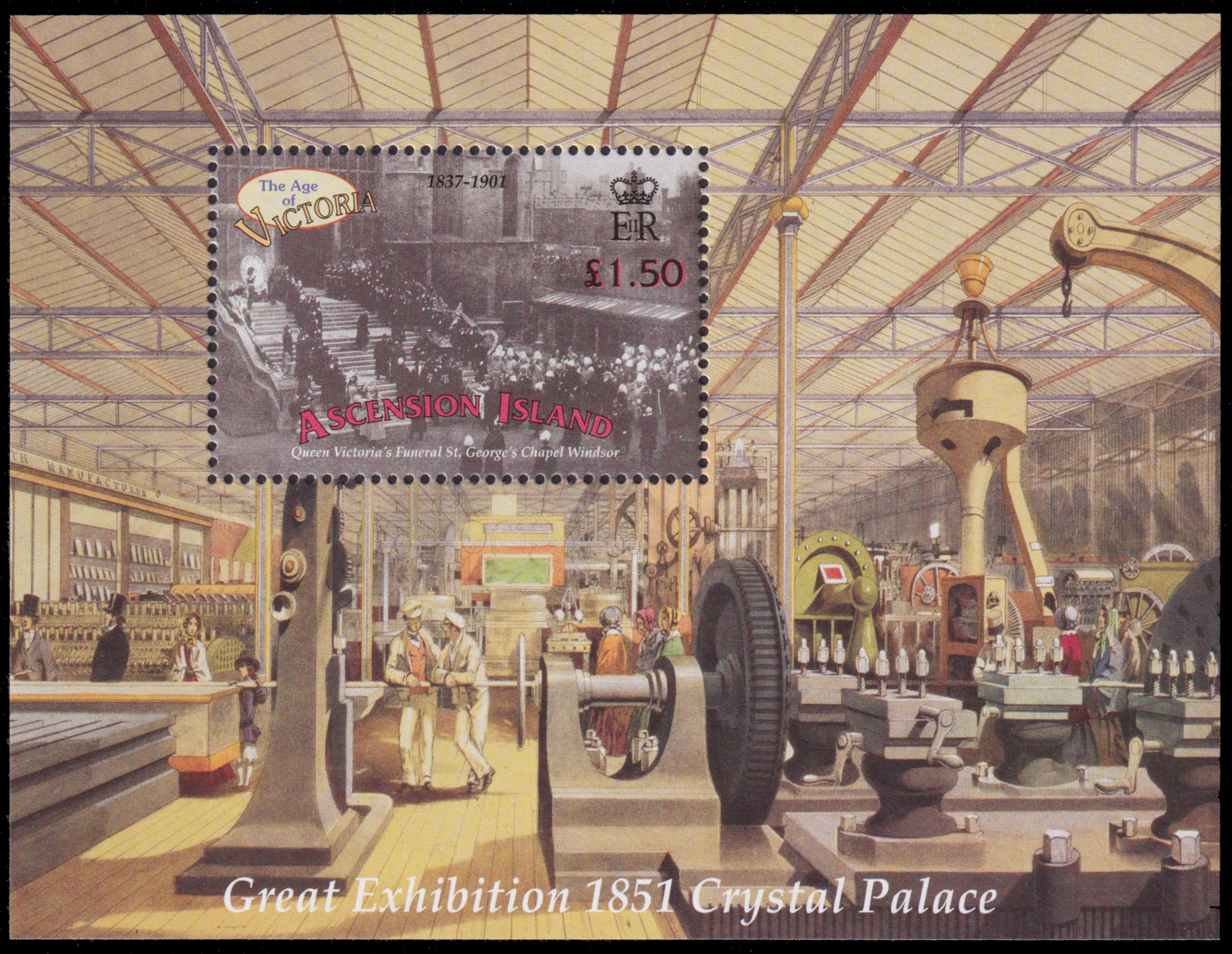

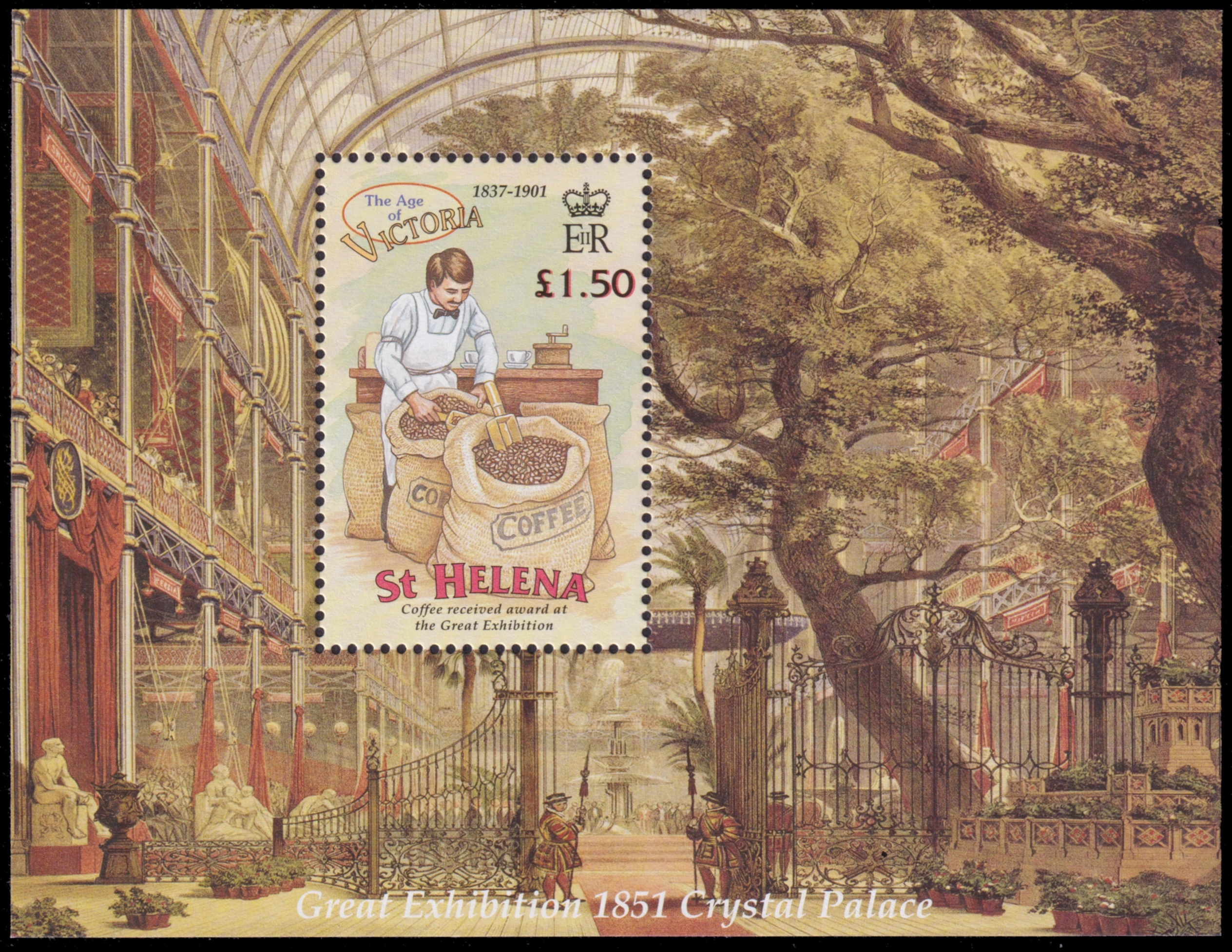

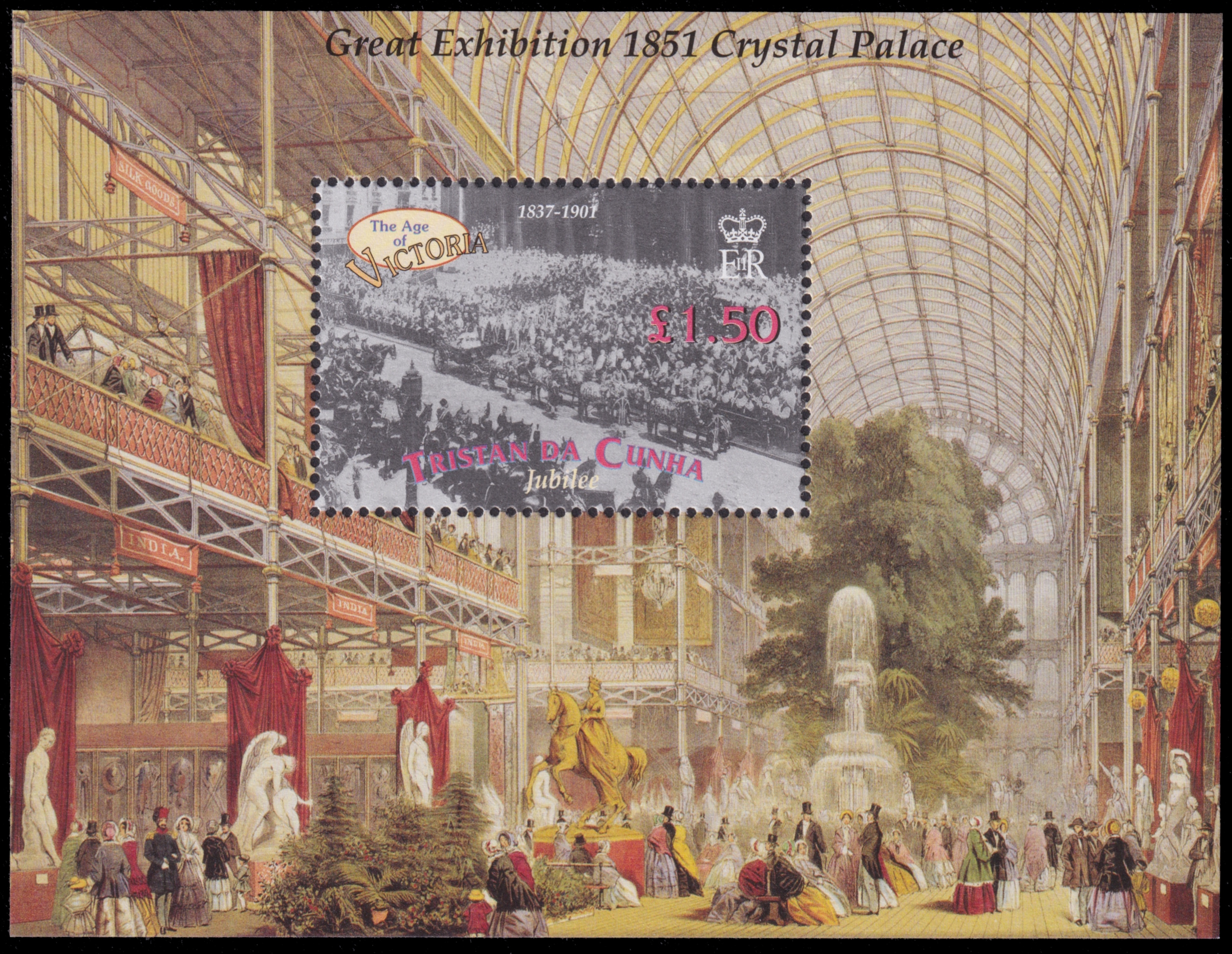

|

|

|

|

Several exhibition halls of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations (1851),

depicted on postage stamps issued by the British Overseas Territories of

Ascension Island, St. Helena, and Tristan da Cunha in 2001.

MiNr.: Bl. 43, Bl. 29, Bl. 37; Scott Nos.: 783, 768, 684, respectively.

|

The Exhibition attracted many prominent figures of the age, including leading paleontologists such as

Gideon Mantell and Henry De la Beche - an English geologist and paleontologist,

the first Director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, and the first President of

the Palaeontographical Society.

De la Beche was also the creator of

Duria Antiquior

(1830),

the earliest reconstruction of a prehistoric scene, known today as

paleoart,

which included the first scientific restorations of

ichthyosaurs as crocodile-like reptiles,

based on fossils found at Lyme Regis, Dorset, mostly by the professional fossil collector

Mary Anning.

Charles Darwin, by contrast, explicitly

stated that he did not attend the Great Exhibition, citing ill health and his aversion to large crowds.

Richard Owen was appointed to judge sections of the Exhibition and was present on the opening ceremony.

He was nominated Chairman of

Jury IV

of the Exhibition, responsible for the division on

Vegetable and Animal Substances, chiefly used in Manufactures, as Implements or for Ornaments

,

and a member of

Jury V

on

the Animal Kingdom

.

The Great Exhibition was primarily a celebration of industrial innovation, manufacturing, and

modern technology. Nevertheless, fossils and geological specimens played a visible and symbolically

significant role, reflecting the Victorian fascination with deep time, natural history, and the geological

foundations of industry.

Fossils were displayed mainly within the British and colonial sections devoted to geology

and raw materials, rather than as part of a separate paleontological exhibition.

These displays included fossil plants, invertebrates, and vertebrates, shown alongside building stones,

coal, ores, and minerals.

Their juxtaposition emphasized the idea that modern industrial progress was rooted in geological resources

formed over immense spans of time.

The Exhibition also highlighted the work of Britain’s leading geological institutions.

Fossils from the Geological Survey of Great Britain, established in 1835 as the world’s first national

geological survey, and from the Museum of Practical Geology, founded in 1835 too, to display specimens relevant

to mining, manufacturing, and construction, illustrated both scientific discovery and practical utility.

Together, these displays reinforced the Victorian belief that geology was a science essential to industry,

empire, and progress.

At the time of the Great Exhibition (1851), no complete dinosaur skeleton was yet known,

and the only mounted mammoth skeleton on public display was in St. Petersburg, Russia.

The first mounted mammoth skeleton in Western Europe would not appear until 1869,

when it was assembled in Brussels, Belgium.

A bronze-cast group of aurochs, an extinct species of bovine considered the wild ancestor of modern domestic cattle,

and a model of horse anatomy were exhibited by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, who was

a noted artist specialising in the depiction of modern and prehistoric animals,

was engaged the following year to create the first life-size sculptures of prehistoric animals,

including dinosaurs, for Crystal Palace Park.

Queen Victoria formally opened the Great Exhibition on 1 May 1851 and became one of its most prominent

supporters.

During its six-month run, she visited the Crystal Palace 37 times,

three times with her family and 34 times privately, an unusually high level of royal engagement.

Her repeated presence publicly endorsed the Exhibition, reassured critics, and underscored its national

and symbolic importance, as well as her support for Prince Albert’s vision.

The Great Exhibition proved to be an extraordinary success, attracting approximately six million visitors,

equivalent to nearly one third of Britain’s population at the time.

It generated a financial surplus of £186,000 (approximately £33 million today), which was used to establish

major cultural and scientific institutions, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum,

and the Natural History Museum.

These institutions were constructed in the area south of the Exhibition site, later known as Albertopolis,

alongside the Imperial Institute.

The remaining surplus was invested in an educational trust to support grants and scholarships for

industrial research—a legacy that continues to this day.

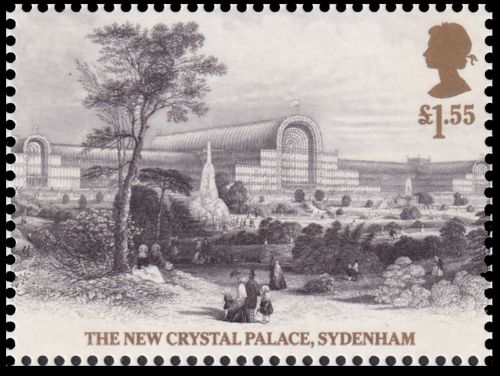

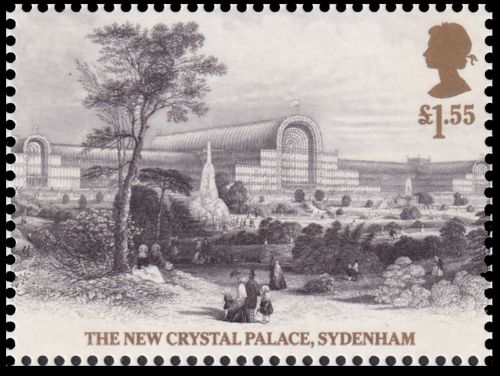

Crystal Palace in Sydenham

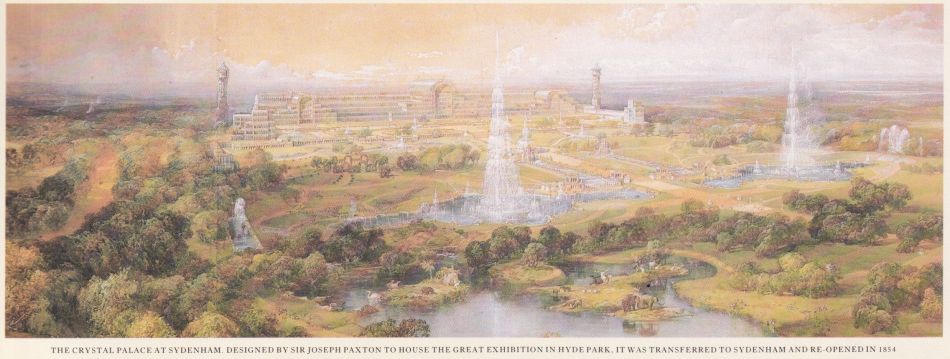

After the Great Exhibition closed, the Crystal Palace was dismantled and rebuilt

between 1852 and 1854 at Sydenham Hill in south London, where it was surrounded by

an extensive landscaped park.

The park and the new palace were designed by Joseph Paxton, the architect of the

original Crystal Palace.

The creation of the park, including terraces, fountains, urns, tazzas, and ornamental

vases, proved even more expensive than reconstructing the Palace itself.

A section of the grounds was dedicated to a reconstruction of prehistoric environments.

In 1852, the sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1803-1865),

who also produced a wealth of drawings, paintings, and lithographs to illustrate the

publications of such influential figures as William Buckland, Gideon Mantell,

Richard Owen, Charles Darwin and Thomas Huxley,

was commissioned to produce 33 life-sized models of extinct animals, completed in 1854,

but execution of some models continued till April 1855.

The geological landscapes were designed by geologist David Thomas Ansted (1814-1880)

and executed by mining engineer James Campbell.

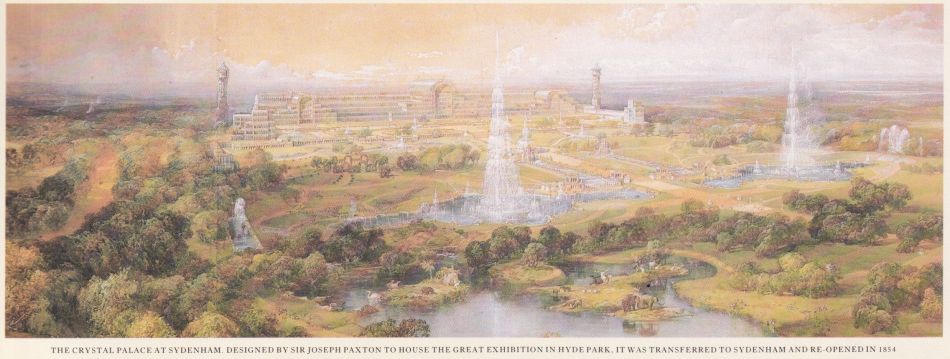

The Crystal Palace at Sydenham designed by Sir Joseph Paxton.

The image is from the presentation pack of Royal Mail 1987

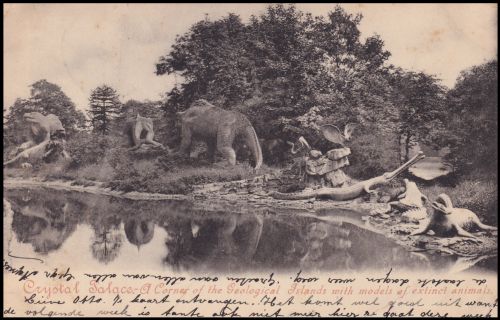

Geological Court or Dinosaurs Island

The prehistoric animal models were created by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins under the scientific guidance of

Professor Richard Owen, reflecting Owen’s interpretations of extinct life.

The first choice of the Crystal Palace Company to supervise the reconstructions of prehistoric animals

was Dr. Gideon Mantell, a rival of Professor Richard Owen.

Mantell had described Iguanodon in 1825 and was among the most renowned paleontologists

in Great Britain at the time, owing to the significance of his work in the early understanding of dinosaurs.

However, Mantell was disagreed with the context-free, specimen-free presentation of the sculptures.

He believed that the reconstructions should be accompanied by conventional fossil displays and explanatory panels,

allowing visitors to understand the scientific evidence behind the prehistoric animals rather than encountering

the figures in isolation.

Together, the models represented 15 genera of extinct animals, including three dinosaurs,

Megalosaurus bucklandii,

Iguanodon mantelli, and

Hylaeosaurus armarus -

the same genera Owen grouped under the name

Dinosauria in 1841.

|

Mary Anning (1799–1847) was a self-taught English fossil collector whose discoveries along the Jurassic Coast

were central to the emergence of early paleontology.

Despite lacking formal scientific training, her deep knowledge of local geology and exceptional ability to

identify fossils earned her recognition within the predominantly male scientific circles of the 19th

century.

Her excavations supplied specimens to numerous British and overseas scientists, contributing significantly

to the reconstruction of Earth’s geological history.

|

Mary Anning on stamp of Great Britain 2024,

MiNr.: 5391, Scott: .

|

The assemblage showcased many of the most celebrated paleontological discoveries of the period,

drawn largely from the work of British scientists.

These included

- dicynodonts from the New Red Sandstone of the Cape Province, South Africa,

- labyrinthodont amphibians from the English Midlands,

- Liassic

ichthyosaurs and

plesiosaurs from Lyme Regis, based largely on the

discoveries of

Mary Anning,

- the alligator-like Teleosaurus from the Lias of Whitby,

- pterodactyls, with wings originally made of leather sewn, from the Oolite and Chalk formations.

Prehistoric mammals were also represented, including

- Megaloceros giganteus,

displayed with real fossil antlers

and then widely known as the

Great Irish Elk

(fossil antlers of Megaloceros giganteus were abundant in Great Britain,

making it unproblematic to sacrifice one for the sculpture),

- the giant South American ground sloth Megatherium from Pleistocene deposits.

Due to budget cuts in 1855, several models of prehistoric mammals, including a half-completed

woolly mammoth, were never installed on the

Tertiary [Early Cenozoic Era] Island.

George Baxter's colour print of the Crystal Palace after its move to Sydenham, with some of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkin's sculptures featured in the foreground.

Megalosaurus is on the left, going after Hylaeosaurus, the pair of Iguanodons is in the right.

George Baxter's colour print of the Crystal Palace after its move to Sydenham, with some of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkin's sculptures featured in the foreground.

Megalosaurus is on the left, going after Hylaeosaurus, the pair of Iguanodons is in the right.

Hawkins established a workshop on site in the park and constructed the models there.

Before work began, he personally studied the fossil remains of the animals in the British and Hunterian museums,

measuring their bones and examining their anatomy.

The prehistoric animals were built full-size in clay, from which a mould was taken

allowing cement sections to be cast.

The larger sculptures are hollow with a brickwork interior.

There was also a limestone cliff to illustrate different geological strata.

The sculptures and the geological displays were originally called "the Geological Court".

The models in the "Court" were displayed on three islands acting as a rough timeline,

the first island for the Palaeozoic Era, a second for the Mesozoic,

and a third for the Cenozoic.

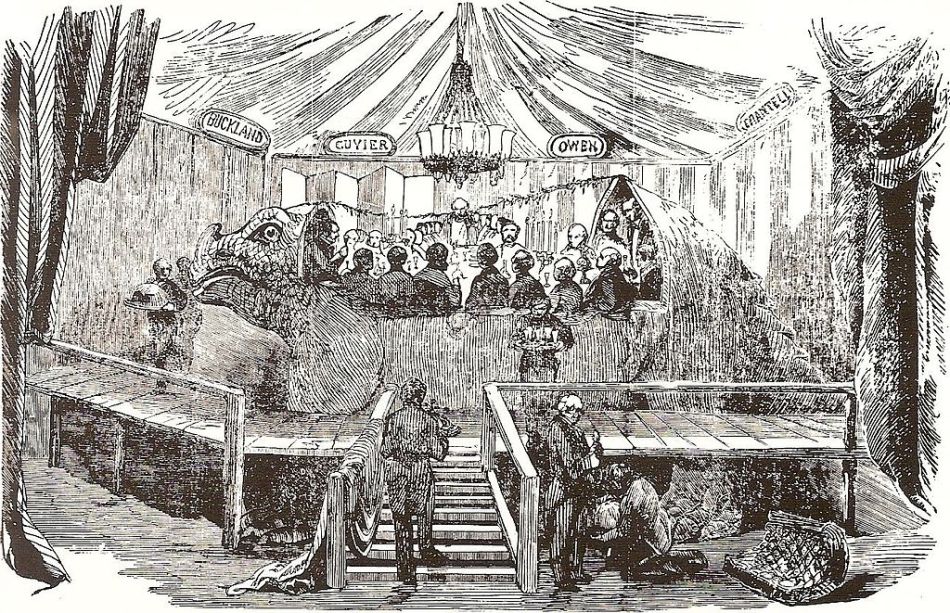

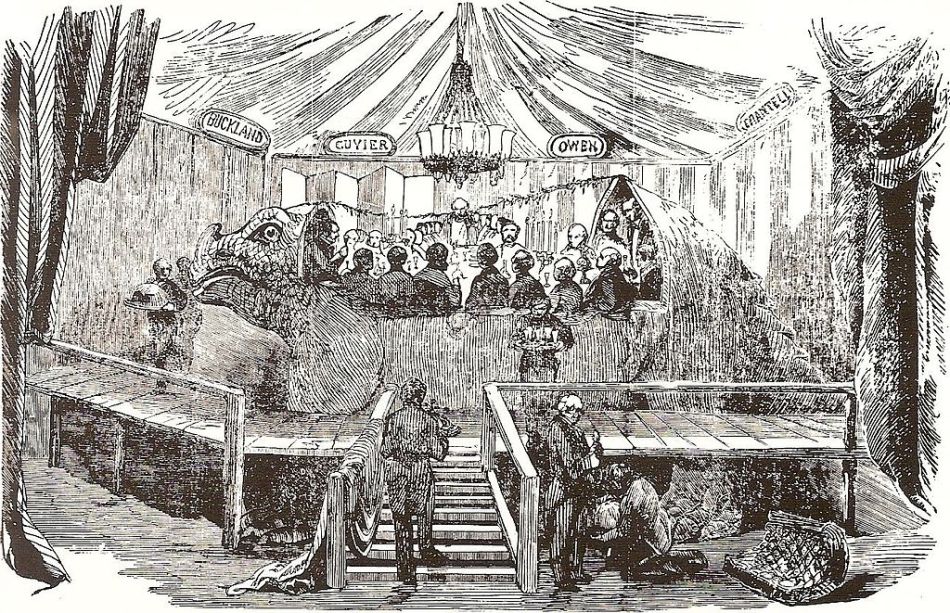

To celebrate the completion of the dinosaur models and attract maximum press attention, Hawkins hosted a dinner on

New Year’s Eve, 1853, inside the mould of one of the

Iguanodon model.

The

Iguanodon was chosen because it was the largest of the commissioned exhibits.

The event took place in Hawkins’s studio, and he invited a distinguished group of guests, including scientists,

investors in the Crystal Palace project, and newspaper editors, to enjoy an eight-course feast.

Most sources mention 21 guests, while others list 22 to 28, with Richard Owen noting 28 guests in his 1894 biography.

Eleven guests were seated inside the dinosaur mould itself, while the remainder dined at an auxiliary table positioned

at right angles to the beast.

The space was decorated with a pink-and-white draped awning, from which pennants bore the names of notable naturalists

such as Cuvier, Mantell, and Buckland.

Due to the model’s height, a small stage was constructed to allow both guests and waiters to access the interior

chamber - perhaps the same stage used by Hawkins’s team while working on the sculpture.

The guest of honour, Richard Owen, was seated inside the head, at the “brain” of the dinosaur, while Hawkins took the

central position and delivered a short presentation about the sculptures.

The Crystal The Dinner in the Dinosaur, sketch by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins,

published in the Illustrated London News, January 7th 1854.

The image was reproduced by Royal Mail in 1991 in the presentation pack for

The Crystal The Dinner in the Dinosaur, sketch by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins,

published in the Illustrated London News, January 7th 1854.

The image was reproduced by Royal Mail in 1991 in the presentation pack for

150th Anniversary of Dinosaurs' Identification by Sir Richard Owens

.

After the dinner, Hawking carried on promoting his work, seeking to bring it to a wider audience.

On May 17

th, 1854, less than a month before the Crystal Palace at Sydenham opened to the public,

he addressed the London Society of Arts with a lecture on the Geological Court and its construction.

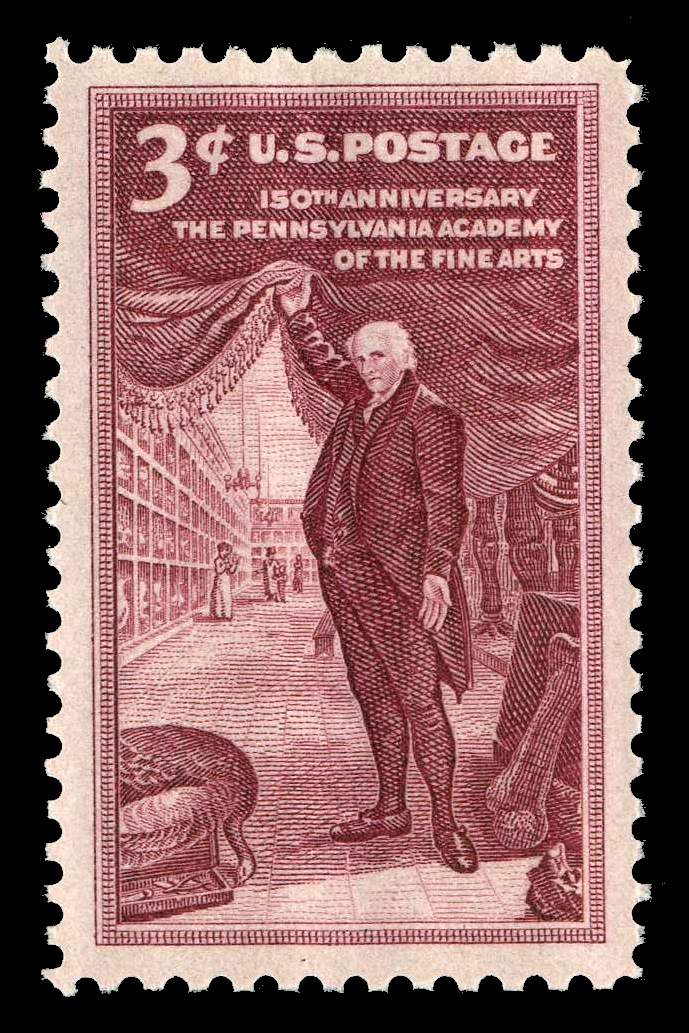

The “Dinosaur Dinner” was not the first dinner held with a prehistoric “beast.”

More than fifty years earlier, in February 1802, thirteen men, including

father of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (John Isaac Hawkins),

dined beneath a reconstructed mastodon skeleton in

Peale’s Museum in Philadelphia.

The dinner was organized by Rembrandt Peale, son of Charles Willson Peale,

who had excavated, assembled, and publicly displayed the first nearly complete

American mastodon skeleton, which had been on view in the museum since late

December 1801.

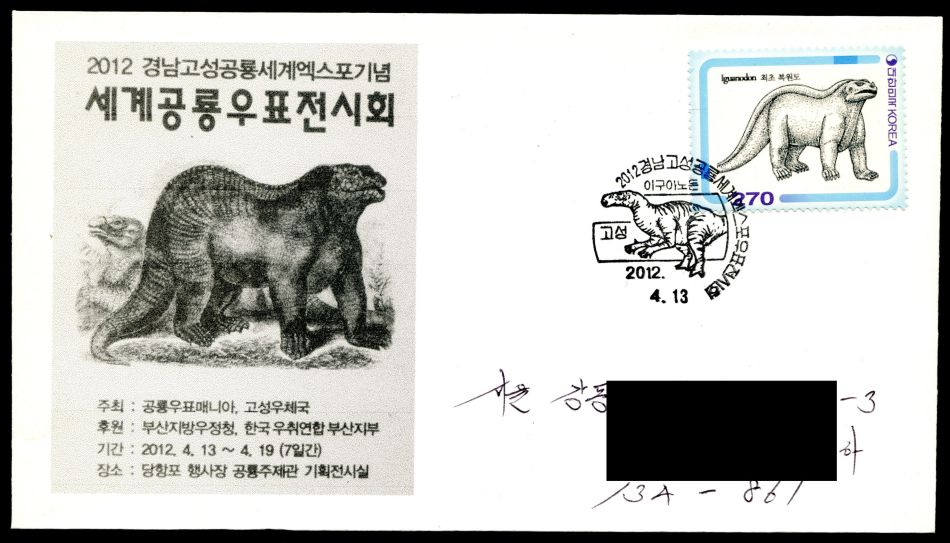

The

Iguanodon model was made as a heavy, four-footed brute with stumpy, pillar-like legs,

a squat, bulky body, and thick, scaly skin.

This reconstruction ignored Gideon Mantell’s suggestion,

later confirmed by the 1878 discovery of

Iguanodon skeletons at Bernissart, Belgium,

that the animal’s forelimbs were smaller and adapted for seizing and grasping rather

than weight-bearing.

The dinosaur models may have been conceived as massive, lumbering creatures partly because

of Owen’s belief in the “Great chain of being”, a prevailing concept in which animals were arranged

in a linear progression from primitive to advanced forms.

Within this framework, long-extinct reptiles were not expected to possess complex

or “advanced” features comparable to those of modern mammals.

|

|

|

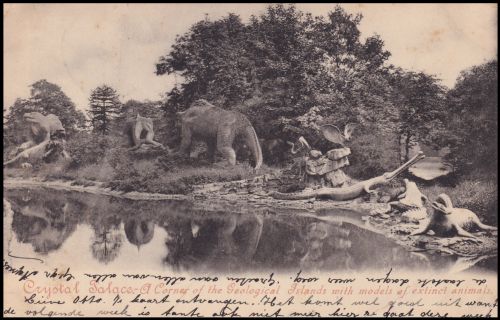

The "Dinosaurs" on the corner of the Geological Islands, in the Crystal Park,

on British postcard,

posted from the Netherlands in 1915.

|

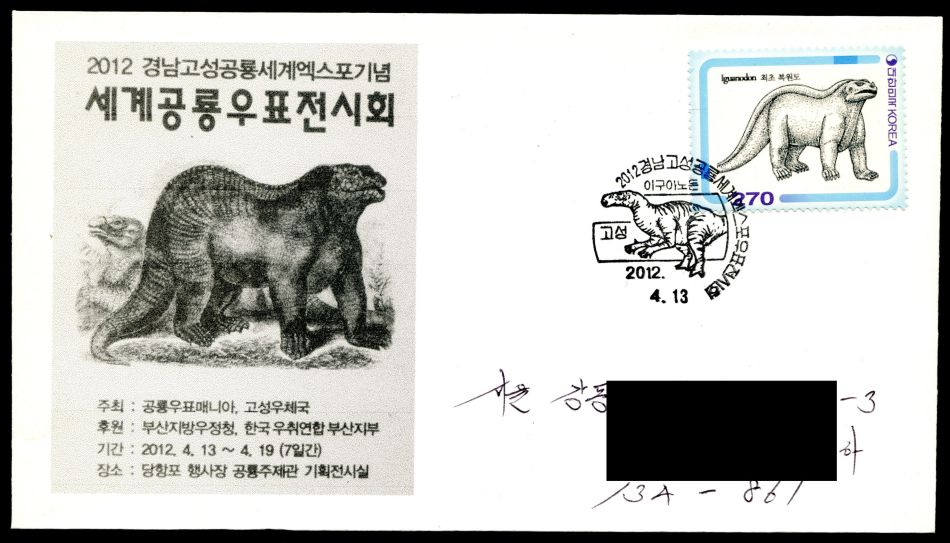

The Iguanodon models of Hawkins at the Crystal Park, on the personalized stamp

and cachet of personalized FDC, South Korea 2012.

The postmark show modern reconstruction of Iguanodon.

|

|

|

Crystal Palace after rebuilt at Sydenham on stamp of Great Britain 2019,

MiNr.: 4399, Scott: 3852c.

|

|

|

|

|

Queen Victoria on stamps of Ascension and the Falkland Islands (2001),

based respectively on her portraits from 1843 and 1859,

MiNr.: 850, 815; Scott: 781, 786.

|

Until Hawkins created the statues, dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals were

poorly understood and attracted limited interest beyond a small community of

professional

paleontologists.

Although the models made these extinct creatures more accessible to the public,

many contemporaries, including some of Hawkins’s guests, continued to interpret them

as pre-Adamite, antediluvian animals.

By the mid-19th century, as increasing numbers of fossils from previously

unknown animals were unearthed, people began to accept the reality of extinction.

To reconcile these finds with biblical tradition, some suggested that certain animals

had missed Noah’s Ark or were simply too large to be taken aboard.

These vanished creatures were commonly described as “antediluvian”.

As a result, the geological past was often viewed as a record of a vanished world

rather than as part of a continuous natural history linked to modern life.

The Crystal Palace in Sydenham was opened by Queen Victoria on June 10

th, 1854,

but was tragically destroyed by fire on 30 November 1936 and never rebuilt.

Among the approximately 40,000 spectators and invited guests were Richard Owen,

attending in the company of Prince Albert, the French Emperor, and the King of Portugal.

Charles Darwin was also present with his wife Emma and some of their children.

During the occasion, Mr Samuel Laing, the chair of the Crystal Palace Company,

introduced Professor Owen and Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

to the Queen, remarking that through their efforts

the gigantic Iguanodon, the Ichthyosaurus, and other monsters of the antediluvian

world will now present themselves to the eye as they once disposed themselves

and pursued their prey amid the forests and morasses of

the Secondary [Mesozoic Era] and

Tertiary [Early Cenozoic Era] periods.

Although many of the statues appear odd and outdated by modern standards,

they are now recognised as historically significant.

They represent the first serious attempt to reconstruct a prehistoric world

with three-dimensional life-size sculptures, accessible by wide public, who would

need to pay for a ticket, however, and played a crucial role in awakening public

interest in paleontology.

The first dinosaur sculptures installed in a public space and freely accessible

to everyone, without the need to purchase an entrance ticket, were erected in

the Soviet Union in 1932 on the Crimean Peninsula, then part of

the Soviet Union and located in present-day Ukraine.

These sculptures of of fighting Brontosaurus with Ceratosaurus

were later commemorated on the cachet of

a Soviet postal stationery

issue released in 1991.

In 1859, five years since the openings of the Geological Court in the Crystal Palace Park,

Charles Darwin issued his most famous work -

The Origin of Species

,

which revolutionised the view on animals origin and their

evolution.

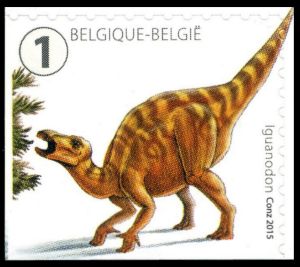

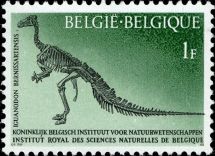

Discovery of Iguanodon skeleton

In 1878,

the first nearly complete dinosaur skeletons were unearthed in Belgium

when coal miners working at a depth of about 322 metres in the Bernissart coal mine unexpectedly encountered large fossil bones

preserved in clay-filled fissures.

|

|

|

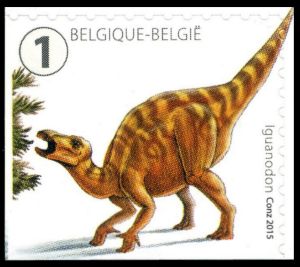

Skeleton of one of the Iguanodons discovered at Bernissart in 1878,

and its reconstruction on stamps of Belgium 1966 and

2015,

MiNr.: 1427, 4603; Scott: 664, 2776, accordantly.

|

|

|

|

Iguanodon on postmark and the cachet of the commemorative cover of

South Korea 2012.

The cachet shows an Iguanodon who uses its thumb for defence and forage purposes.

|

Over the following years, more than 30

Iguanodon skeletons were recovered,

many of them remarkably complete and articulated.

The Bernissart discoveries fundamentally transformed scientific understanding of dinosaurs.

They confirmed Gideon Mantell’s earlier view that

Iguanodon was not a sprawling, lizard-like reptile,

and they challenged reconstructions popularised by Richard Owen and the Crystal Palace models.

At the same time, the discoveries supported Richard Owen’s doubts about the famous thumb spike.

Owen had correctly suggested that it was not a nasal horn.

Following the discovery of several articulated dinosaur skeletons, the thumb spike was correctly

recognised as part of the hand.

Recent research suggests, the thumb spike was primarily used as a defensive

weapon, with likely secondary roles in feeding, where it may have helped in

handling vegetation.

During the early–mid 20

th century,

paleontologists reassessed

Iguanodon anatomy and biomechanics.

They concluded that

Iguanodon was primarily quadrupedal, especially when walking slowly or feeding,

though it was probably capable of rearing up or moving bipedally for short periods.

The stiff tail, shoulder structure, and weight distribution made a permanently upright posture unlikely.

20

th century revisions of the fossils used by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

to create the dinosaur models revealed that many bones originally assigned by Victorian palaeontologists

to a single species,

Iguanodon mantelli, actually belonged to several different taxa.

Mantell, Owen, and other scientists of the period were therefore working with material now attributed

to multiple iguanodontian species, including

Iguanodon bernissartensis,

Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis, and

Barilium dawsoni.

The Natural History Museum in London

When the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations closed its doors in October 1851,

it left behind more than memories of glittering machinery and global ambition.

The exhibition generated a substantial financial surplus, and under the guidance of Prince Albert

and the Royal Commission, these profits were reinvested in education and knowledge.

|

|

|

Prince Albert on margin of Mini-Sheet "The Legacy of Prince Albert",

Great Britain 2019, MiNr.: Bl. 123, Scott: 3852.

|

Professor Richard Owen on stamp of Montserrat 1992,

MiNr.: 837, Scott: 794.

|

By this time, Richard Owen had become one of the most prominent naturalists in Great Britain

and was well connected with Prince Albert, members of Parliament, and other influential figures.

His tireless efforts to popularise natural science, together with the enormous public interest

generated by the dinosaur models in Crystal Palace Park, yielded tangible results:

part of the exhibition surplus was allocated to purchase land and, ultimately, to establish a dedicated museum

for natural history.

The project advanced slowly but decisively.

During the 1860s, plans were drawn up for a new, purpose-built museum in South Kensington that would house

the nation’s growing natural history collections, long cramped within the British Museum at Bloomsbury.

In 1864, the land was formally secured, and after years of debate over design and funding, construction finally began

in 1873.

Designed by the architect Alfred Waterhouse, the monumental Romanesque building rose as a cathedral to nature,

embodying the Victorian ambition to place scientific knowledge at the heart of public life.

Professor Richard Owen played a central role throughout the museum’s creation.

He oversaw the arrangement of the collections, advised on the design of display galleries, and ensured that

the building could accommodate the needs of scientific study as well as public exhibition.

Owen’s vision shaped not only the practical layout of the museum but also its educational mission,

emphasizing the connection between fossils, living animals, and the broader story of life on Earth.

His influence is evident in the careful planning of galleries, lecture spaces, and specimen storage,

making the museum both a research institution and a public showcase for natural history.

After nearly a decade of construction, the Natural History Museum officially opened its doors in 1881.

The grand Romanesque halls, adorned with terracotta reliefs of plants and animals,

welcomed the public to explore the wonders of the natural world.

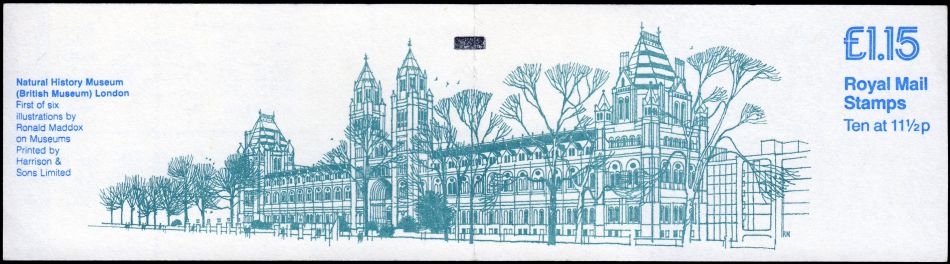

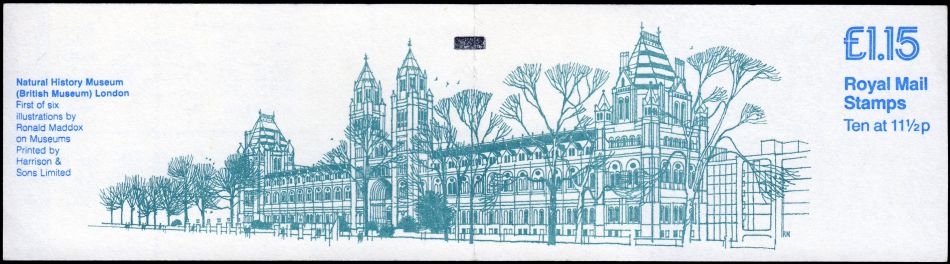

The Natural History Museum in London on the cover of booklet with inland stamps of UK 1981.

The opening of the Natural History Museum on Easter Monday,

April 18

th, 1881 was a carefully orchestrated and symbolic event,

reflecting both the grandeur of Victorian architecture and the importance of science in public life.

By 1881, Queen Victoria was in her later years, and Prince Albert had died twenty years earlier.

Many of the prominent scientists who had contributed to the rise of

paleontology,

as well as the architect of the Crystal Palace and its park, and the sculptor of the dinosaur statues,

had not survived to see the museum’s opening:

Gideon Mantell and Henry De la Beche died in 1855, William Buckland in 1856,

and Joseph Paxton and Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins in 1865.

Nevertheless, many dignitaries, members of Parliament, and leading scientists gathered to witness the inauguration of

the museum’s monumental Romanesque halls.

Richard Owen, then 77 years old and still not yet knighted, whose guidance had shaped the layout of the galleries,

the arrangement of the collections, and the educational mission of the institution, was present and honoured for

his central role in bringing the museum to life.

Owen became the first Superintendent of the museum and held the position until his retirement two years later,

when he was finally knighted by Queen Victoria.

To Owen, the new museum was less a temple to nature than a cathedral of science.

As deeply religious person, he regarded scientific work as a “ministry of truth”

and envisioned the museum as an architectural testament to the rising authority

of scientists as “God’s ministers”, through whom the truths of the natural world

were revealed.

By 1881, Darwin was 72 years old and suffering from ongoing health problems

(chronic fatigue, digestive issues, and heart concerns), which often kept him from attending public events.

He died on 19 April 1882, almost exactly one year after the Natural History Museum in London officially

opened on 18 April 1881.

Darwin’s statue was placed on the main staircase, overlooking Hintze Hall of the Natural History Museum

in 1885, four years after the Natural History Museum opened.

A bronze statue of Sir Richard Owen, created by the sculptor Sir Thomas Brock, was installed on

the Hintze Hall staircase in the Natural History Museum following Owen’s death in 1892.

For many years the statue stood on the main staircase in the museum’s grand central hall,

acknowledging Owen’s foundational role in establishing the institution.

Over the course of the 20

th century, the placement of Owen’s and Darwin’s statues shifted —

Owen’s bronze took centre stage in the hall after his death, while Darwin’s stone figure was positioned elsewhere

— reflecting changing attitudes toward their scientific legacies.

In 2009, to mark the bicentenary of Darwin’s birth and the museum’s embrace of evolutionary science,

Darwin’s statue was restored to its original prominent position on the staircase and Owen’s was relocated to

an upper floor.

The establishment of the Natural History Museum in London marked a turning point in the public and

scientific engagement with paleontology, building on the pioneering work of Victorian naturalists such as Richard Owen,

Gideon Mantell, William Buckland, and Henry De la Beche.

Their meticulous collections, bold reconstructions, and sometimes spirited debates about dinosaur anatomy,

evolution, and the age of the Earth laid the foundation for rigorous scientific

practice and inspired generations to come.

Over the 20

th and 21

st centuries, the museum became a hub for British and international researchers,

fostering ground-breaking discoveries in fossils, prehistoric ecosystems, and evolutionary history.

Today, the Natural History Museum stands as a testament both to the vision of its Victorian founders and

to the ongoing global pursuit of knowledge about life on Earth, bridging the rich heritage of early paleontology

with the discoveries and innovations of the modern era.

Related articles of this website

References

Books related to this article

-

The Dinosaur Hunters: A True Story of Scientific Rivalry and the Discovery of the Prehistoric World

,

by Deborah Cadbury, published in 2000,

ISBN: 978-1857029598

-

Richard Owen: Biology without Darwin

,

by Nicolaas Rupke, published in 2009,

ISBN: 978-0226731773

-

Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

,

by Mark P Witton and Ellinor Michel, published in 2022,

ISBN: 978-0719840494

Internet resources

- Queen Victoria:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

BBC.

- Prince Albert:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- British Industrial Revolution:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Postal Reform:

The first stamps and postal stationery and the beginning of Philately,

The Beginning of Philately.

- Great chain of being:

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Crystal Palace:

- The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations (1851):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Official descriptive and illustrated catalogue (Internet Archive),

Scientific American,

Crystal Palace Park Trust,

The Crystal Palace Foundation.

- Crystal Palace Park (1852-1854):

Wikipedia,

"Clift, Darwin, Owen and the Dinosauria.." (The Linnean. 7 (2): 8–14. January 1991),

- Crystal Palace Dinosaurs (1852-1854):

Wikipedia,

Lind Hall,

NHM UK,

Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs:

"The Crystal Palace Dinosaur statues",

"What are the ‘Crystal Palace Dinosaurs’?".

- Dinosaur Dinner (1853):

Wikipedia,

Geological Society of London,

The History Press,

BBC.

Museums and Colleges mentioned in the article

Societies mentioned in the article

|

British naturalists mentioned in the article

- Gideon Mantell (1790-1852):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

The Guardian.

- William Buckland (1784-1856):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

- Richard Owen (1804-1892):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

BBC.

- Charles Darwin (1809-1882):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Darwin Online.

"Charles Darwin in Philately".

- Henry De la Beche (1796-1855):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery (PDF file).

- Thomas Huxley (1825-1895):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Mary Anning (1799-1847):

"Mary Anning pioneering fossil hunter and palaeontologist".

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

NHM UK.

Contributors to British naturalists mentioned in the article

Personalities related to Crystal Palace and Geological Court

- Henry Cole (1808-1882):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Joseph Paxton (1803-1865):

Wikipedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1803-1865):

Wikipedia,

Strange Science,

Mark Witton Blog,

Mental Floss.

- David Thomas Ansted (1814-1880):

Wikipedia,

- James Campbell (birth and date years unknown):

"The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs", by Mark Witton and Ellinor Michel, published in 2022,

ISBN: 978-0719840494, page 26.

- Samuel Laing (1812-1897):

Wikipedia,

|