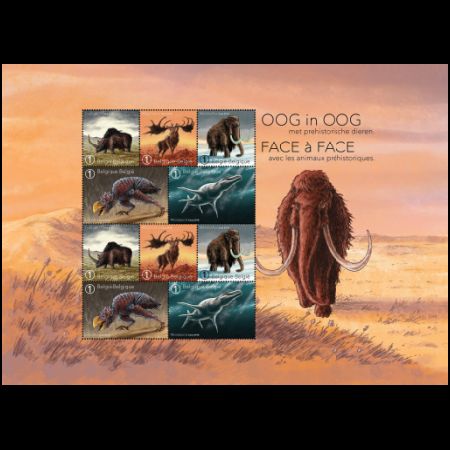

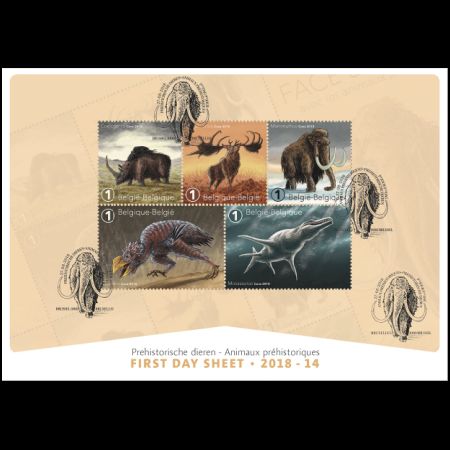

Belgium 2018 "Face to face with prehistoric animals"

| <prev | back to index | next> |

| Issue Date | 27.08.2018 |

| ID | Michel: 4851-4855, Scott: 2871-2875, Stanley Gibbons:, Yvert et Tellier: 4778-4782 Category: pR |

| Designer | Conz (Constantijn van Cauwenberge) |

| Stamps in set | 5 |

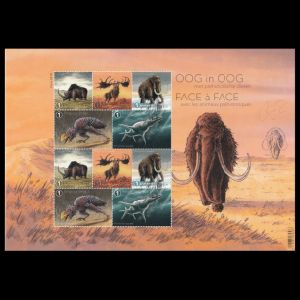

| Values | Domestic letter rate of letters up to 50gr. = Euro 0.84 Prehistoric animals on stamps: Coelodonta (Woolly Rhinoceros from Cenozoic era) Megaloceros (Giant Deer from Cenozoic era) Mammuthus (Woolly Mammoth from Cenozoic era) Gastornis (Terror bird from Cenozoic era) Mosasaurus (Marine Lizard from Mesozoic era) |

| Emission/Type | commemorative |

| Issue place | Brussels |

| Size (width x height) | Stamps: 40mm x 40mm, 60mm x 40 mm Mini Sheet: 297mm x 210mm (A4 horizontal) |

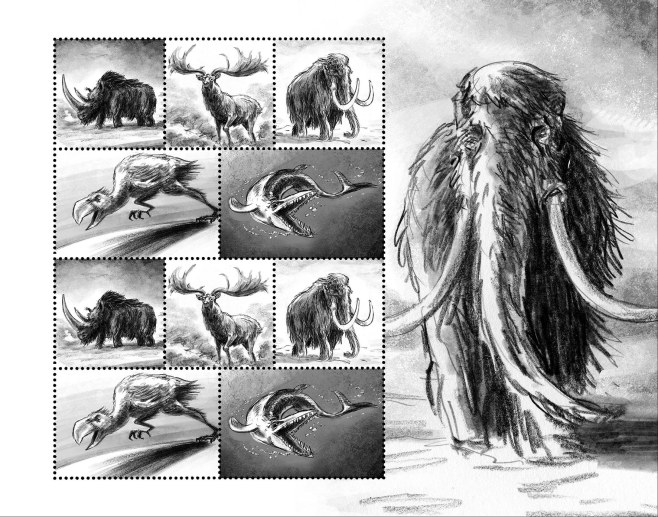

| Layout | Mini Sheet of 10 stamps with mammoth on the margin |

| Products | FDS (First Day Sheet) x1 |

| Paper | gummed white FSC |

| Perforation | 11.5 |

| Print Technique | Offset, 4 colours |

| Printed by | Stamps Production Belgium |

| Quantity | 92,840 sets |

| Issuing Authority | La Poste De Post Belgique |

On August 27, 2018, the Post Authority of Belgium issued a set of 5 stamps of various prehistoric animals with the title "Face to face with prehistoric animals".

These stamps were issued in a large sheet: two sets of 5 stamps and a very large margin.

All stamps have the same domestic rate, equal to 82 Euro-cents on the day of issue. One stamp can be used to pay a letter of weight up to 50g. Two stamps are enough to pay postage for a letter up to 100g.

These stamps were designed by Belgian cartoonist/designer Conz – the pseudonym of Constantijn Van Cauwenberghe, who designed "The fearsome Dinosaurs" stamps of Belgium in 2015.

The Conz explain about his work:

(The following text is based on a google translation)

For the issue about dinosaur stamps I made only 10 drawings. The design was in hand by bpost designer Myriam Voz. This time I did everything on my own: the design of the sheet, the drawings and the layout. I felt honored to be allowed to do this.

There are five different images on the stamps, supplemented by a sixth, larger image on the sheet. In consulting with bpost, I selected animals that were discovered in Belgium - ‘Belgian’ animals, so to say.

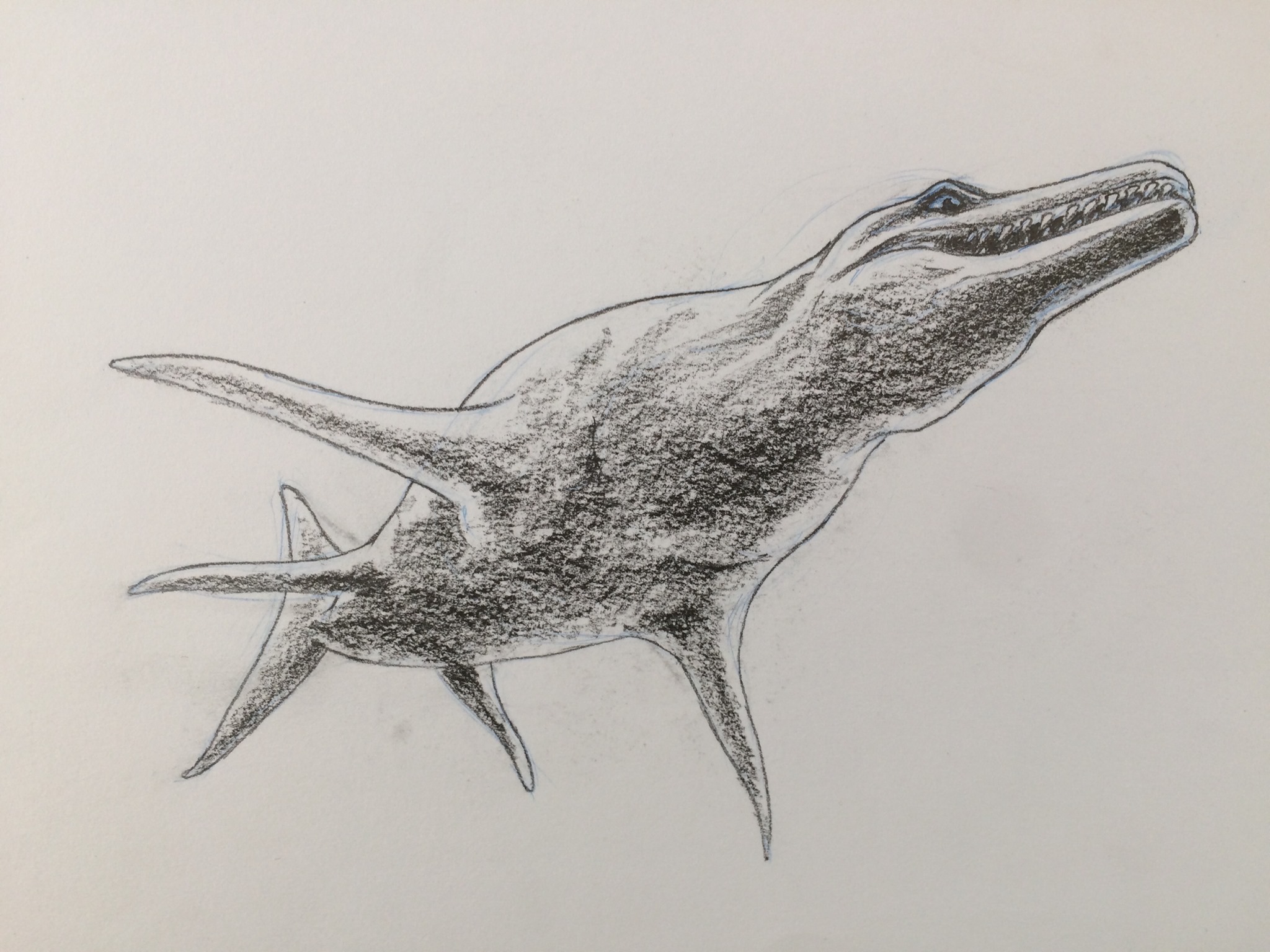

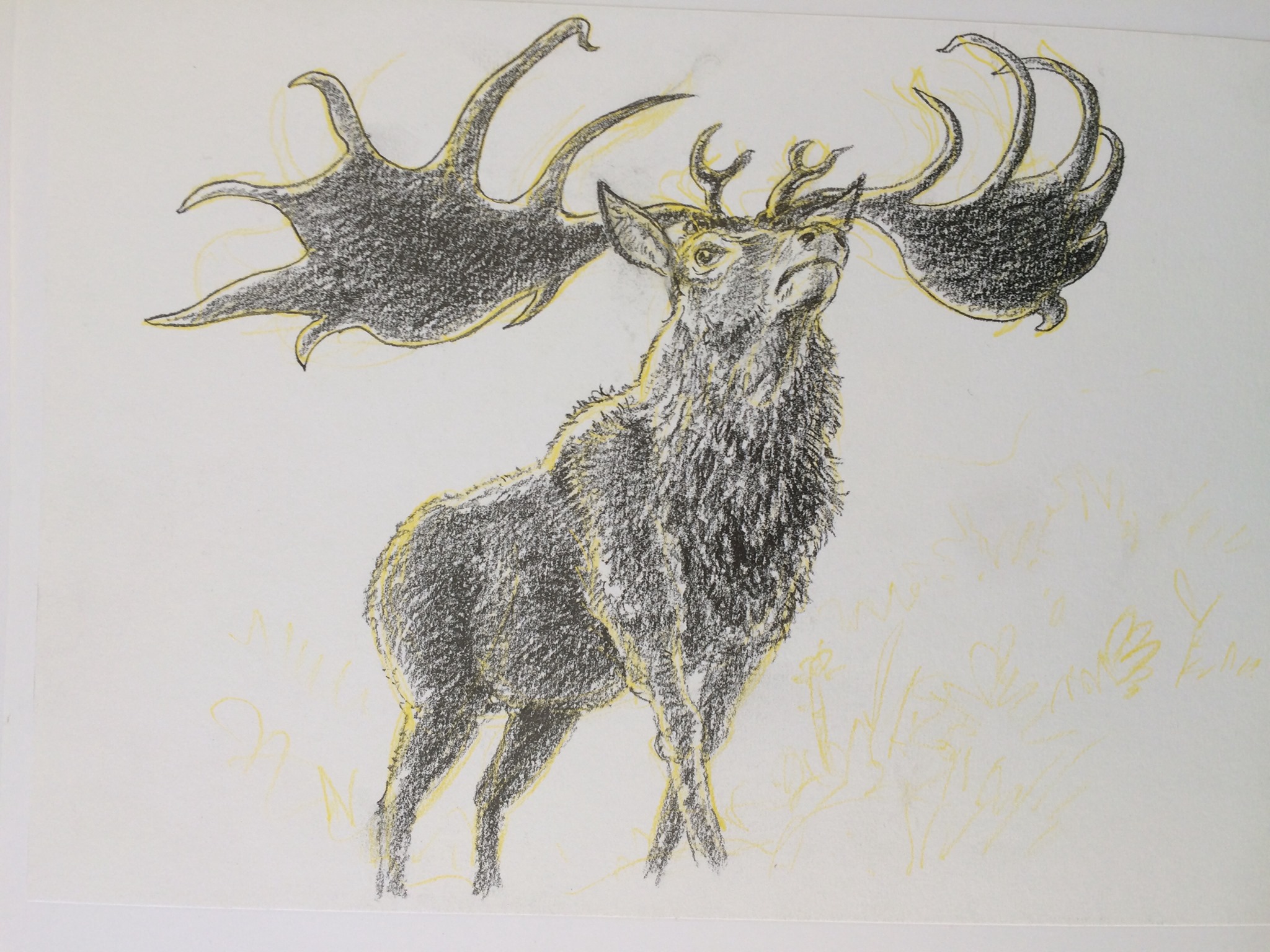

Conz at work on "Face to face with prehistoric animals" stamps of Belgian Post (bpost).

Photos credit: provided by Conz. Photographer: David Samyn.

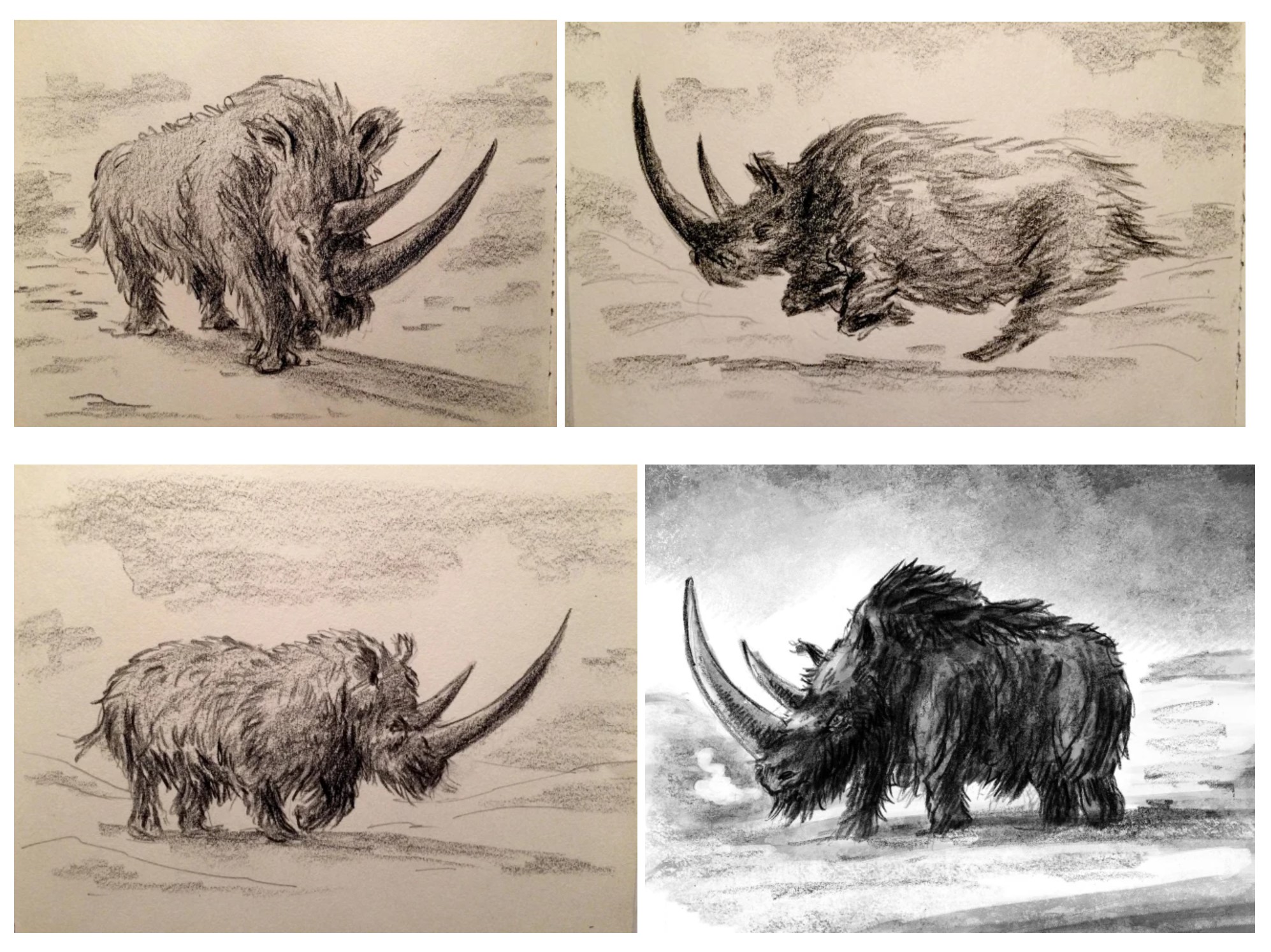

As soon as I knew which animals would be featured, the process of sketching began. I tried different poses and thus puzzled the ideal one issuance together.

The drawing of animals involved a lot of research to make my work as accurate as possible. For extinct species you only have scientific works as basis. I found a lot of online muscle and muscle information skeletal reconstructions. Also, the Natural History Museum provided me with some additional documents. As they did before, when I worked on the issue of dinosaur stamps.

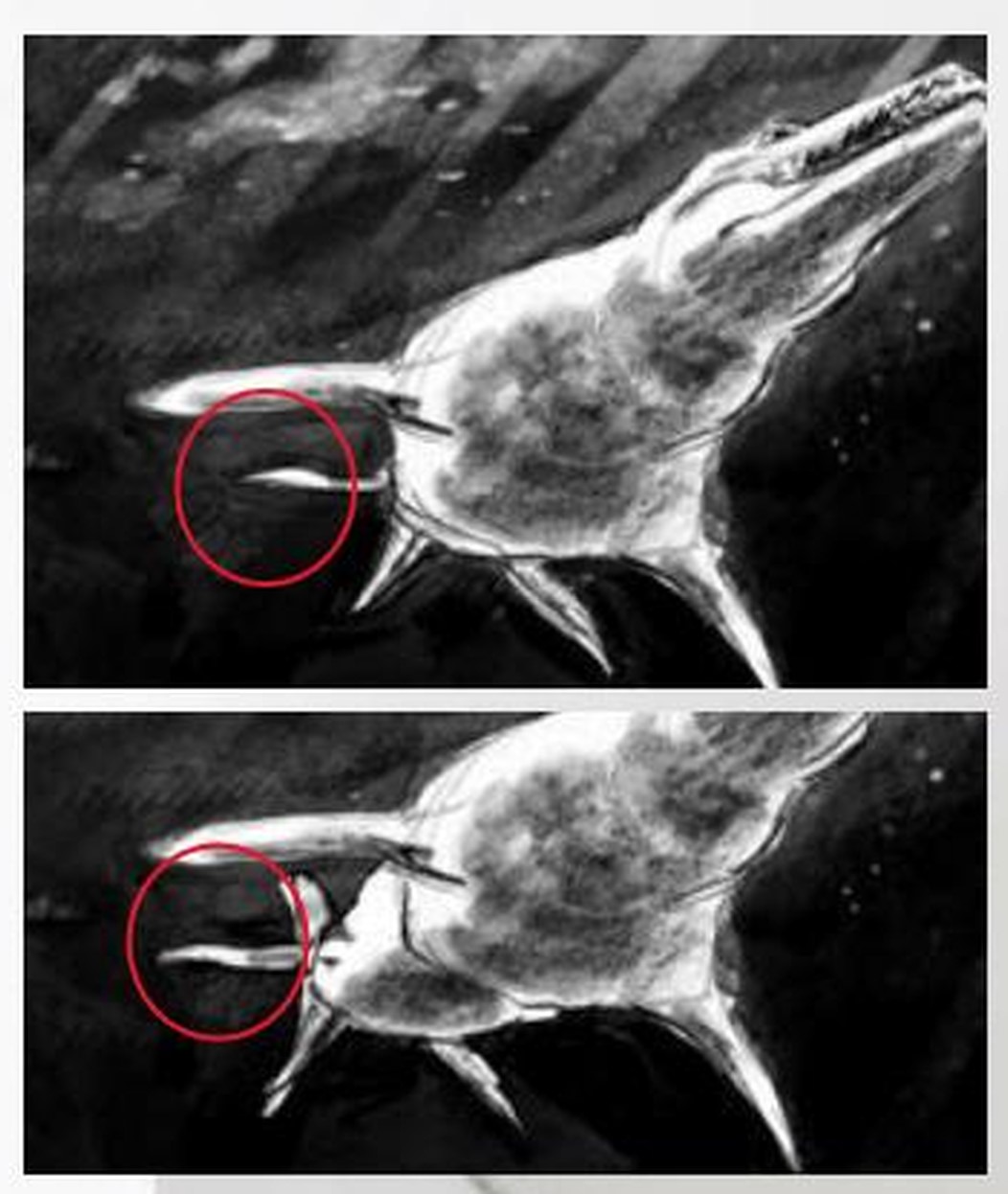

I discussed with the museum's experts my final sketches. From this I came to know that certain things were not quite right: the end of the Mammoth's trunk I still needed to adjust, but also, the fins position of the Mosasaur were wrong.

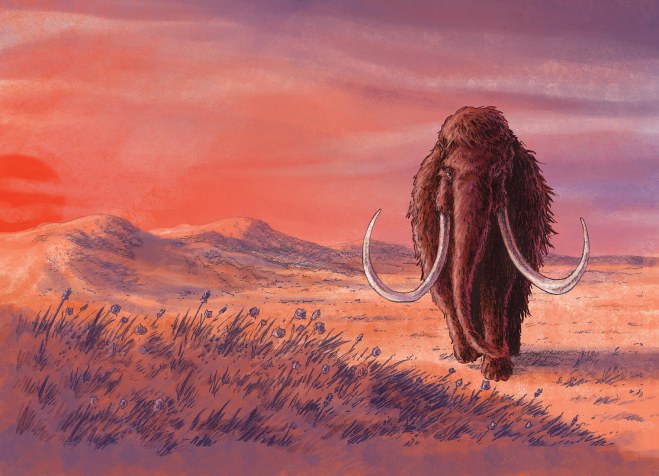

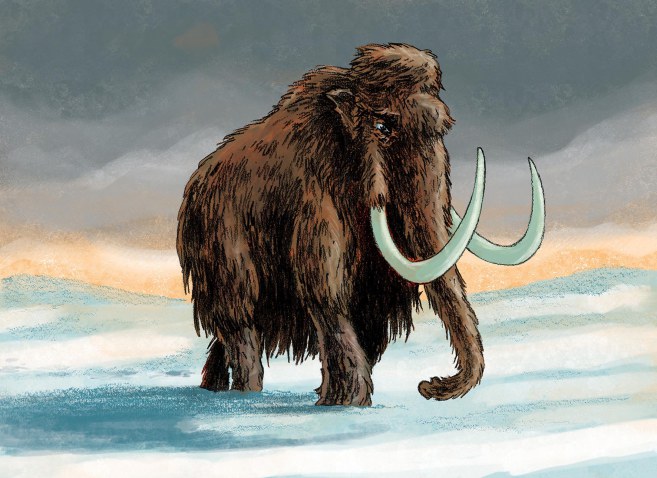

I originally chose a snow background, but – it turns out – that during the Ice Age there was periods of thawing. Then you got a tundra-like landscape. I dug into that and created different backgrounds. I drew them without animals. Later I placed landscape and animals digitally together, so that I can more easily edit them. That's just how it is the mammoth is still on a carpet of snow. The other animals I placed in the air, underwater or in a thawed tundra landscape.

- Coelodonta (Woolly Rhinoceros from Cenozoic era)

- Megaloceros (Giant Deer from Cenozoic era)

- Mammuthus (Woolly Mammoth from Cenozoic era)

- Gastornis (Terror bird from Cenozoic era)

- Mosasaurus (Marine Lizard from Mesozoic era)

|

| Woolly Rhinoceros on stamps of Belgium 2018, MiNr.: 4851, Scott: 2871. |

The woolly rhinoceros was a member of the Pleistocene megafauna.

The animal was massive, with two large horns toward the front of the skull, and was covered with a thick coat of hair, that allowed it to survive in the extremely cold, harsh mammoth steppe.

It had a massive hump reaching from its shoulder and fed mainly on herbaceous plants that grew in the steppe. Mummified carcasses preserved in permafrost and many bone remains of woolly rhinoceroses have been found. Images of woolly rhinoceroses are found among cave paintings in Europe and Asia. The species became extinct at the end of the Last Glacial Period, with its decline probably predominantly driven by unfavourable environmental change caused by a warming climate.

In Belgium, more specific in the Flemish Valley, large quantities of mammalian remains are found in several localities. The Flemish Valley is a paleo-valley dating from the Middle Pleistocene; it was filled up during the Weichselian. The Weichselian is the last glacial interval of the Pleistocene ice age. The richest assemblages of the Flemish Valley are Zemst IIB, dating from the very beginning of the Weichselian and Hofstade I, dating from the Middle Weichselian.

The fossils accumulated mainly through gradual, long-term processes as indicated by the scattered and dispersed spatial distribution of the bones in the fluvial deposits, the abundance of scavenged and weathered bones and the low numbers of carnivores.

The bones are from mammals that died within the confines of the river valleys, due to predation, disease, accident or old age.

Remains of large grazing mammals (woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, steppe bison, and horse) dominate the faunal assemblages.

One of the biggest discovery of Coelodonta fossils in Belgium happened in 1907, during railroad construction near Hofstade.

Fossils of around 13 woolly rhinoceros were unearthed there.

Today, the remains of these prehistoric animal are preserved in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.

The photo from 1910 (on the right) shows preparators freeing woolly rhinoceros fossils from Hofstade from their plaster casts.

As can be seen on the right side, the skulls are ready. The man in the black costume is palaeontologist Louis Dollo, who spent a big part of his career studying the Bernissart Iguanodons.

|

|

|

| Sketches of Coelodonta stamp, created by Belgian artist Conz (Constantijn van Cauwenberge). Unadopted Sketches on the left. | ||

|

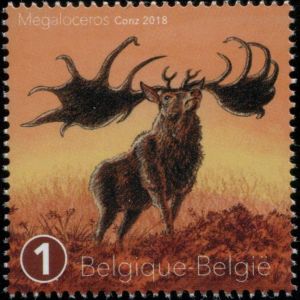

| Megaloceros giganteus on stamp of Belgium 2018, MiNr.: 4852, Scott: 2872. |

This deer, contemporary of the Mammoth and the woolly Rhinoceros, was indeed a giant, as males were up to 700 kg in weight and stood about 2.1 meters tall at the withers.

They carried proportionally huge antlers with a maximum tip to tip length of 3.65 meters. The antlers were up to 50 kg in weight, which are the largest antlers of any known deer.

The type and only certain member of the genus, Megaloceros giganteus, vernacularly known as the "Irish elk" or "giant elk", is also the best known.

Although several other species of Megaloceros are known, the Irish elk was the largest.

Despite its distribution throughout Eurasia, the species was most abundant in Ireland. However, the first skeleton of Megaloceros giganteus was discovered on Isle of Man.

Around 17,000 years ago humans saw these glorious creatures and created their own interpretations of them on the cave walls at Lascaux, and others at Cougnac. These exquisite paintings depict Megaloceros giganteus with speckled coats and dark shoulder hair that accentuated a distinctive hump. Due to the fact that the hump does not show in fossils, the cave art really helps with reconstruction of the animal.

Near complete skull of Megaloceros was discovered in Nieuwdonck, Berlare municipality in Belgium.

It has been found in an artificial lake made in an old sand quarry which itself was dug in an old meander of the river Schelde. It is in private collection to date.

Some isolated bones of Megaloceros were also found in Wallon caves. Belgium is a very rich country when it comes to Pleistocene mammals but the lack of complete specimens is due to the taphonomic conditions. Most of the finds were made in fluvial sediments. After the winter, most of the animals that died were transported by floods and wild river systems, hence the scattered fragments.

In the Walloon region there are cave systems that housed big predators. The specimens of herbivores, including some bones of Megaloceros, found there were brought there by those predators.

|

|

|

| Sketches of Megaloceros stamp, created by Belgian artist Conz (Constantijn van Cauwenberge). Unadopted drawing on the left. | ||

|

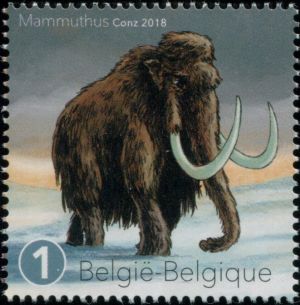

| Woolly Mammoth on stamps of Belgium 2018, MiNr.: 4853, Scott: 2873. |

The woolly mammoth began to diverge from the steppe mammoth about 800,000 years ago in East Asia. Its closest extant relative is the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). The Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) lived alongside the woolly mammoth in North America, and DNA studies show that the two hybridised with each other.

Woolly mammoths stood about 3 to 3.7 metres tall and weighed between 5,500 and 7,300 kg. The woolly mammoth’s ears were small, which exposed a smaller amount of surface area and was likely an adaptation to the cold climates in the Northern Hemisphere.

A mound of fat, which served as an energy and water reserve, was present as a hump on the back. The woolly mammoth was herbivorous, consuming the stems and leaves of tundra plants and shrubs.

The woolly mammoth is by far the best-known of all mammoths.

|

|

|

| Sketches of Woolly Mammoth stamp and entire stamps Sheet, created by Belgian artist Conz (Constantijn van Cauwenberge) | ||

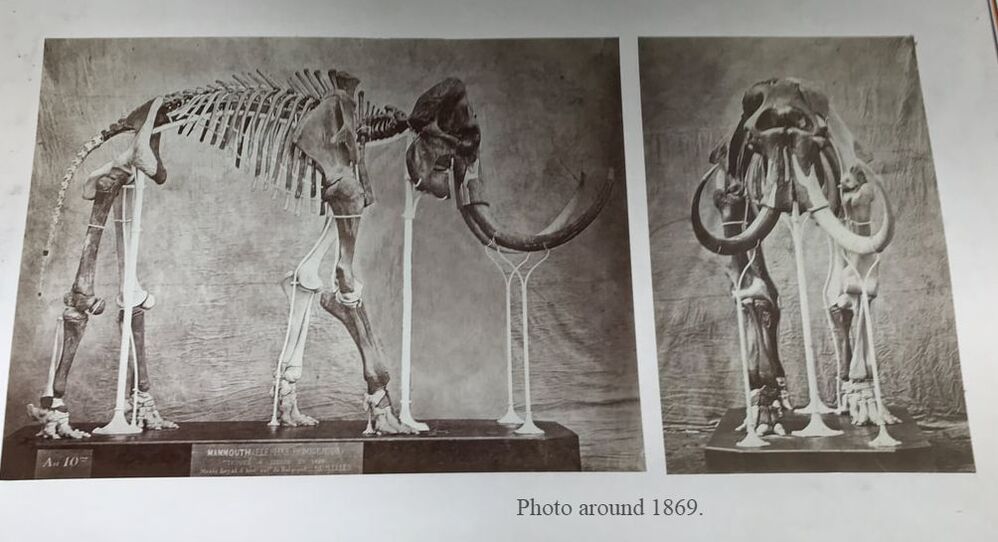

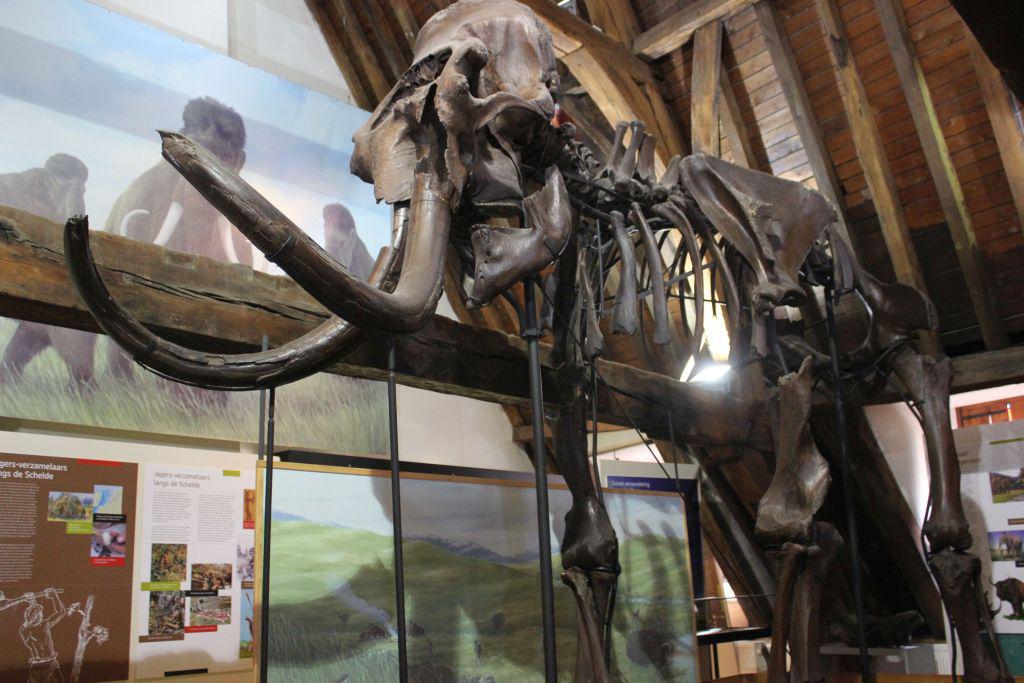

The first fossil of woolly mammoth was discovered in Belgium in 1860. The partial skeleton of the mammoth was discovered near the Dungelhoeffkazerne in Lier in the Province of Antwerp of Belgium, while digging the diversion canal of the Nete river.

Its importance was recognised by a military doctor stationed in Lier, François-Joseph Scohy, and the skeleton was excavated, mounted and in 1869 for the first time shown to the public.

According to the length of the right tusk that was found (the left one is reconstructed) the skeleton belongs to a male animal, who died at an age of 30-35 years old.

It was the first skeleton of Mammoth mounted in West Europe and the second in the world.

The first mounted skeleton of Mammoth was the "Adam's Mammoth" in St. Petersburg, Russia. It was presented to the public in 1808.

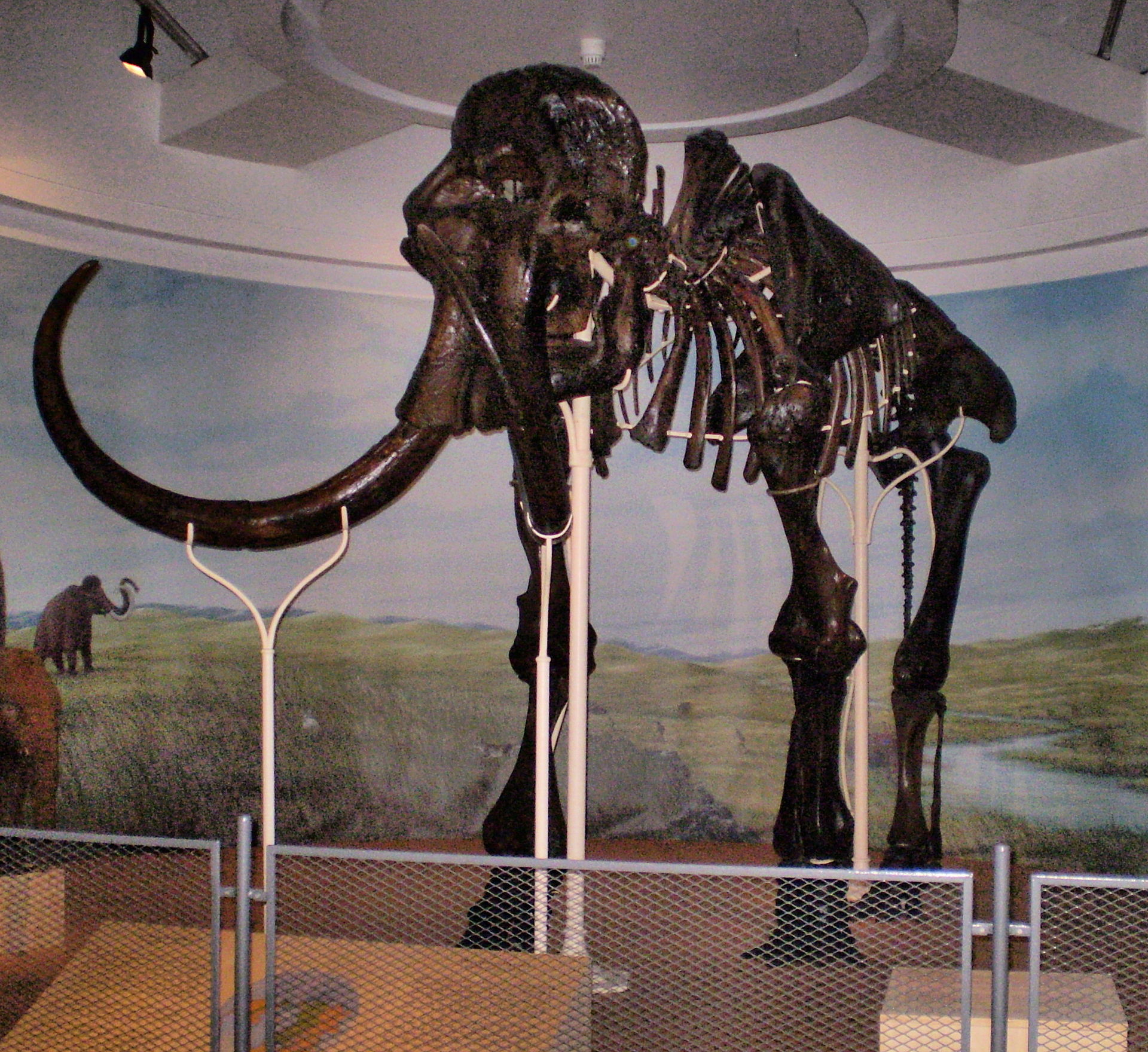

Today, the Lier Mammoth skeleton is preserved in the museum of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels and a 3D printed replica is present at Lier city museum.Because the skeleton is incomplete, some bones were recreated in wood. Originally, all recreated bones were white, but today, the replicated bones are painted the same color as the original bones and cannot easily be recognized.

|

|

| A photo of original bones of the Lier Mammoth - the recreated bones were white | Today, the bones of the Lier Mammoth are painted a brown color. Image credit: Wikipedia |

Another Mammuthus primigenius skeleton (the skull is completely intact, both tusks are still there, the right half of the rib cage, one thoracic vertebra, hips and a left hind leg) was discovered in Belgium in 1862, during the construction of Fort 8 in Hoboken.

Fort 8 Hoboken is one of the eight Brialmont forts: the concrete and natural stone forts that were built in 1860-1864 by captain and fort architect Henri Alexis Brialmont. Unlike the other forts, it was the only one not modernized after 1907. Yet it is one of the best preserved Brialmont forts.

The Hoboken Mammoth is believed to be a small male - or a hefty female - between 48 and 60 years old who lived during the last ice age. The animal was about 3 meters long, 2.5 meters high and weighed 4 tons. The skeleton is estimated to be between 10,000 and 30,000 years old.Today, the remains of the prehistoric animal are preserved in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.

|

| Dendermonde Mammoth. Image credit: Wikimedia |

In 1968, 16 years old Hugo De Potter found a bone in a sand extraction site in Dendermonde. His biology teacher suspected that it was a mammoth vertebra. During the next 4 years De Potter collected a big amount of mammoth bones. These are mammoths that probably died in the Scheldt basin. Their bodies floated to the lowest point.

The city of Dendermode claimed the collection and moved it to the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels.

In 1975, the skeleton was mounted in the upper floor of the Vleeshuismuseum in Dendermonde. The skeleton consists of 74 original elements. Some of these elements originate from the Hofstade collection of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels.

The skeleton is near-complete, but the foot- and hand bones are missing. These bones, however, belongs not to one individual but to many different mammoths.

"The skull and tusks are male, the pelvis is clearly female", said Anthonie Hellemond, head of the Belgian Palaeontology Association, who leads the restauration.

Gastornis is an extinct genus of large flightless birds that lived during the mid Paleocene to mid Eocene epochs of the Paleogene period.

|

| Gastornis on stamps of Belgium 2018, MiNr.: 4854, Scott: 2874. |

Gastornis species were very large birds, and have traditionally been considered to be predators of small mammals.

However, several lines of evidence, including the lack of hooked claws in known Gastornis footprints and studies of their beak structure and isotopic signatures of their bones have caused scientists to reinterpret these birds as herbivores that probably fed on tough plant material and seeds.

Gastornis is generally agreed to be related to Galloanserae, the group containing waterfowl and gamebirds.

These were generally very large birds, with huge beaks and massive skulls superficially similar to the carnivorous South American "terror birds".

The largest known species, G. gigantea could grow to the size of the largest moas, and reached about 2 meters in maximum height.

Gastornis was first described in 1855 from a fragmentary skeleton. It was named after Gaston Planté, described as a "studious young man full of zeal", who had discovered the first fossils in clay (Argile Plastique) formation deposits at Meudon near Paris.

The discovery was notable due to the large size of the specimens, and because, at the time, Gastornis represented one of the oldest known birds.

One of the first discoveries of Gastornis fossils in Belgium, was made at the town of Mesvin. It was described by Belgian palaeontologist Louis Dollo in 1883, who also worked on reconstruction of the famous Iguanodon skeletons discovered in in a coal mine in Bernissart in 1878.

|

|

| Sketches of Gastornis stamp, created by Belgian artist Conz (Constantijn van Cauwenberge) | |

Mosasaurus, an extinct genus of aquatic lizards that attained a high degree of adaptation to the marine environment.

|

| Mosasaurus on stamps of Belgium 2018, MiNr.: 4855, Scott: 2875. |

The earliest fossils of Mosasaurus known to science were found as skulls in a chalk quarry near the city of Maastricht in the Netherlands (a country neighboring Belgium) in the late 18th century, which were initially thought to have been the bones of crocodiles or whales.

One skull discovered around 1780, which was seized by France during the French Revolutionary Wars for its scientific value, was famously nicknamed the "great animal of Maastricht". In 1808, naturalist Georges Cuvier concluded that it belonged to a giant marine lizard with similarities to monitor lizards but otherwise unlike any known living animal. This concept was revolutionary at the time and helped support the then-developing ideas of extinction. Cuvier did not designate a scientific name for the new animal, and this was done by William Daniel Conybeare in 1822 when he named it Mosasaurus in reference to its origin in fossil deposits near the Meuse River.

The exact affinities of Mosasaurus as a squamate remain controversial, and scientists continue to debate whether its closest living relatives are monitor lizards or snakes.

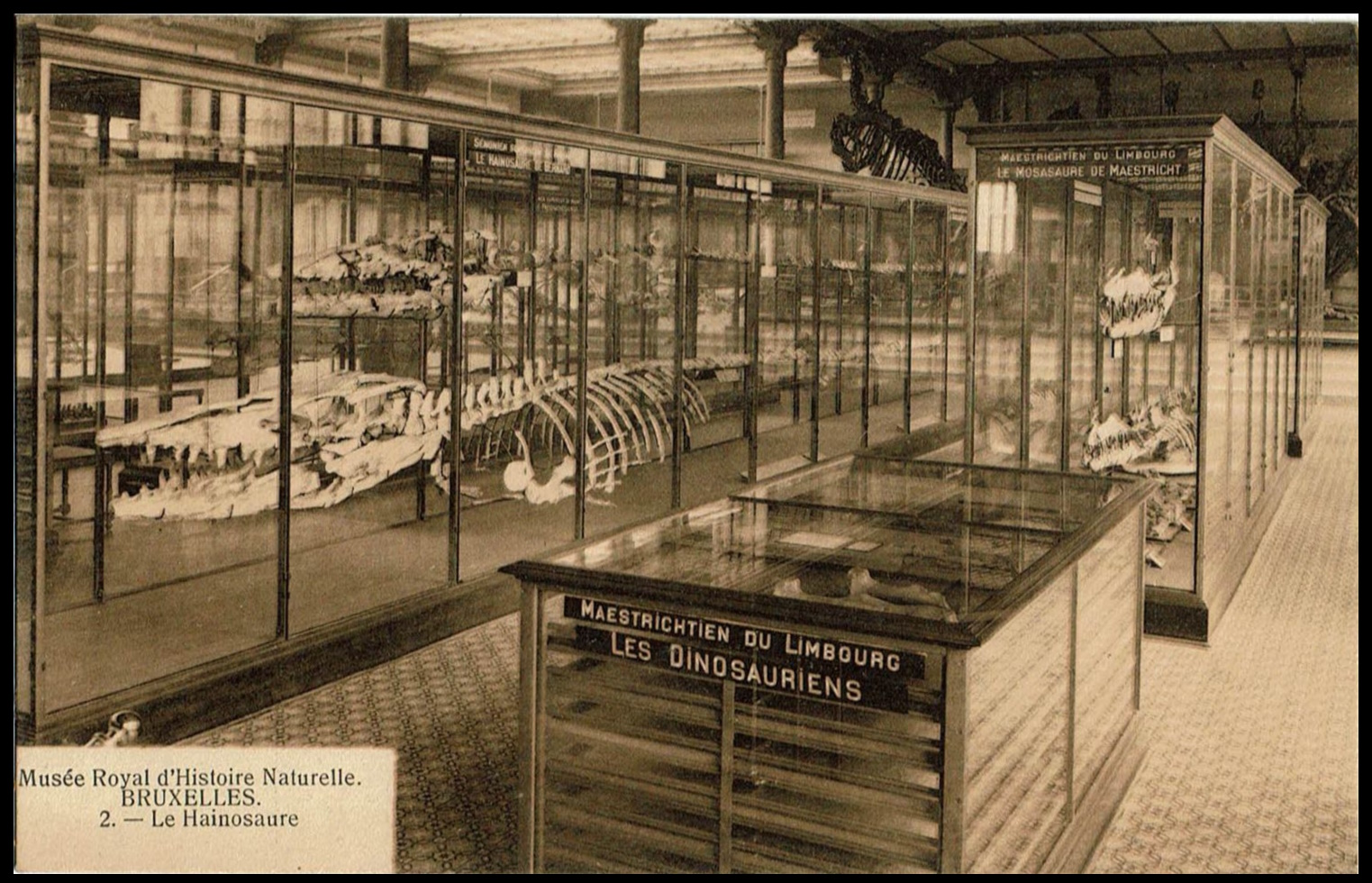

In 1885, Belgian paleontologist Louis Dollo described the genus Hainosaurus from a near-complete but poorly preserved skeleton excavated from a phosphate quarry in the Ciply Basin near the town of Mesvin, Belgium.

|

| Fossils of Hainosaurus on display in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences on a vintage postcard. |

Based on information about the circumstances and locality of the discovery given the museum, it was recognized that the rest of the skeleton may have remained intact.

In February, excavations were made under the authorization of an industrialist named Leopold Bernard, who managed the quarry the fossil resided in.

The rest of the skeleton was recovered after a month of excavating between 500–600 cubic meters of phosphate, although a section of the tail was found to have been destroyed by erosion from an overlying deposit.

The skeleton went to the museum, which was subsequently studied by Dollo, who recognized that it belonged to a new type of mosasaur. By instruction of the museum, he named it Hainosaurus bernardi.

|

| Fossils of Hainosaurus/Tylosaurus bernardi on display in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences today (catalog number: IRSNB R23). Image credit: Wikipedia. |

The prefix Haino- in the generic name refers to the Haine, a river located nearby the Ciply Basin, and thus combined with saurus means "lizard from the Haine"; Dollo wrote that this was erected specifically to complement the etymology of Mosasaurus, which was similarly named in reference to a river near its type locality.

The specific epithet bernardi was in recognition of Leopold Bernard, who made the excavation of the skeleton possible.

Later on, the genus Hainosaurus was renamed to Tylosaurus.

The skeleton is now on display at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.

To date (2023), many Mosasaurus fossils were discovered in Belgium including region around Mons, Ciply and around Eben-Emael.

Mosasaurus fossil on an entrance ticket of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences

Products and associated philatelic items

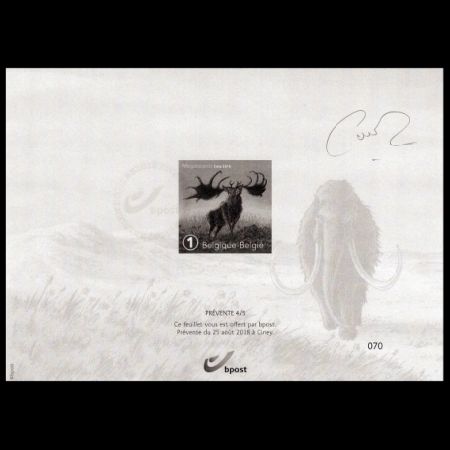

| First Day Sheet | Black print with Megaloceros |

Signed CTO Sheet |

|

|

|

| Signed by the stamp designer (Conz), on the top-right side. | ||

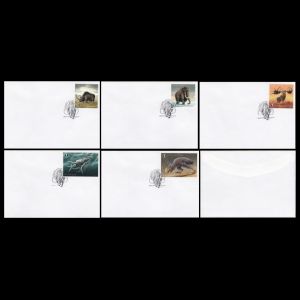

| Customized FDC | ||

|

|

|

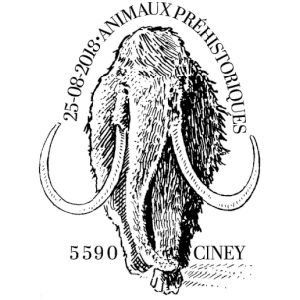

| Special Postmark | First-Day-of-Issue Postmark | |

|

|

|

| Issued two days before the stamps issue: 25.08.2018 for the stamp presentation ceremony, with the text in Dutch. | Both postmarks were issued on the first day of issue and have the same design, but the text on the back of the Mammoth is written on different languages: French versus Dutch. | |

References

|

- Technical details and official press release: bePhila_2018-03 (philatelic bulletin of Belgium's Post),

- Coelodonta (Woolly Rhinoceros) :

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Wikipedia,

worldmuseumofman.org,

the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (the article does not exist anymore)

"Mammoth taphonomy of two fluvial sites from the Flemish Valley, Belgium", by Mietje Germonpré from Royal Belgian Institute for Natural Sciences, Brussels.

- Gastornis : Wikipedia

- Mammuthus (Woolly Mammoth):

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Wikipedia:

- Wikipedia

- 3dprintingindustry

- Lier city museum

Lier mammoth

- The Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (the article does not exist anymore)

Dendermonde mammoth

- stib-mivb.be

Gare du Midi mammoth - Megaloceros (giant deer): "First discoveries of Megaloceros giganteus", Encyclopaedia Britannica Wikipedia

- Mosasaurus :

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Wikipedia.

- Hainosaurus/Tylosaurus Wikipedia.

Acknowledgements

- Many thanks to Dr. Peter Voice from Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Western Michigan University, for reviewing the draft page and his very valuable comments.

- Many thanks to Mr. Kevin Nolis, Administrator of the “Société d'Histoire Régionale de Rance – Musée du Marbre” and secretary of Palaeontologica Belgica, for his help finding an information about the link of the prehistoric animals depicted on the stamps to Belgium.

- Many thanks to Conz (Constantijn Van Cauwenberge, who designed these stamps) for a nice conversation via facebook and for providing images to use on this website.

| <prev | back to index | next> |