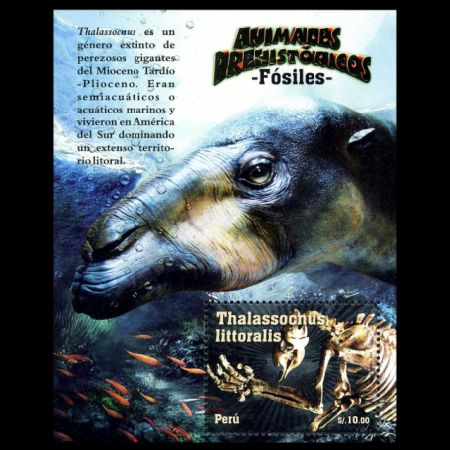

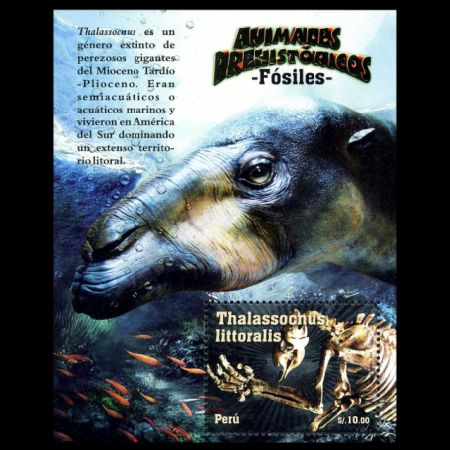

Peru 2010 "Prehistorical animals – Thalassocnus"

| Issue Date |

21.09.2010 |

| ID |

Michel: Bl. 70 (2485);

Scott: 1748;

Stanley Gibbons: ;

Yvert et Tellier: 61;

Category: pR |

| Design |

Cristian Alvarez M. – SERPOST S.A. |

| Stamps in set |

1 |

| Value |

S/. 10.00 -Thalassocnus littoralis:

fossil on stamp and reconstruction in margin

|

| Emission/Type |

commemorative |

| Issue place |

Lima |

| Size (width x height) |

stamp: 30 mm x 40 mm,

Souvenir-Sheet: 80 mm x 100 mm

|

| Layout |

Souvenir-Sheet with 1 stamp |

| Products |

FDC x1 |

| Paper |

|

| Perforation |

13.50 x 14 |

| Print Technique |

Offset |

| Printed by |

Thomas Grag and Sons, Peru |

| Quantity |

10.000 |

| Issuing Authority |

Servicios Postales del Peru SA |

On September 21

st, 2010, the Post Authority of Peru - Servicios Postales del Peru SA (Serpost) -

continued the series started in 2004, “Prehistoric Animals” (Animales Prehistoricos - Fosiles).

These stamps show fossils discovered in the country of Peru.

This year the Souvenir-Sheet shows scientific reconstruction and fossils of a prehistoric sloth -

Thalassocnus littoralis.

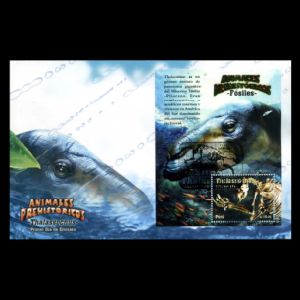

The

reverse side

of the Souvenir-Sheet is numbered.

When you think of marine mammals, sloths are probably the last thing you’d

expect to take to the water.

But from the Late Miocene (7-8 million years ago) to the Late Pliocene (3-1.5 million years ago),

several species of giant ground sloths in the genus

Thalassocnus

did indeed evolve to take advantage of the aquatic environment.

However even some modern sloths can swim.

The text below is translation of

brochure

produced by Serpost in 2010.

The text was written by Rodolfo Salas Gismondi, Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology Department of

Natural History Museum in Lima (UNMSM).

"If there is something amazing about paleontology it is a capacity to show us that the life on the

Earth, such as we know it nowadays, is the result of constant changes.

Even the English naturalist

Charles Darwin

sketched his primordial ideas about the biological evolution inspired by fossilized bones of

giant sloths and Glyptodonts, the ancestors of little tree sloths and armadillos in South America.

The theory of evolution developed 150 years ago in Darwin’s “The origin of the species” -

is the concept that integrates all the sciences of life, now with the help of

genetics and molecular biology.

As in Darwin’s time, fossils are still critical to understanding evolution.

Millions of years ago, the desert area of Sacaco, north to Arequipa, was a littoral marine environment.

In its sands lie hundreds of fossils of whales, dolphins, seals, penguins and

sharks in excellent state of preservation.

In 1967, French paleontologist Robert Hoffstetter visited the area, and was greatly surprised to find

a terrestrial intruder: a sloth between aquatic species.

It was initially assumed that the sloth lived on land, near the littoral.

Hoffstetter thought that their bodies were transported to the sea by an Andean paleo-river,

where they were buried and preserved with aquatic species.

However, something was wrong:

the skeletons were always found articulated and complete, as if buried

in the same place of their death - in the sea.

What if it really was an aquatic sloth?

This possibility, though wild, encouraged paleontologists Christian de

Muizon and Greg McDonald to observe every bone's detail to look for

revealing clues.

In 1995, Muzion and McDonald announced in Nature Magazine, the existence

of a 4-million-year old aquatic sloth in Peru.

Some details of its anatomy, such as the shape of the premaxilla,

femur and caudal vertebrae (the bones that make up the tails of

tailed animals), are more similar to certain aquatic mammals that to others extinct sloths.

Various scientists were skeptical though.

After almost 15 years and many discoveries made by Mario Urbina, 5 species of the aquatic sloth

Thalassocnus were described, all of them found in marine deposits nearby Sacaco,

but in rocks belonging to successive epochs from 9 to 2,5 million years ago.

|

|

Thalassocnus skeleton - image from Wikipedia,

Photographer: FunkMonk.

|

This only record, let us track the first splashes in its linneage evolution, and

also observe the way that certain adaptations to the aquatic environment

were progressively accentuated through time.

Thalassocnus was a sloth the size of a large dog, with long tail and powerful claws.

It had simple teeth with no enamel.

Since the most ancient species (

Thalassocnus antiquus) to the most

modern (

Thalassocnus yaucensis) several changes were observed, especially an

increase in the length and width of the muzzle’s posterior region, related to

obtaining aquatic grass as a new source of food.

The radius bone morphology shows substantial differences in the mode of locomotion.

While

Thalassocnus antiquus has a long radius bone with a reduced supinator crest, typical of

terrestrial sloth, in

Thalassocnus yaucensis the radius bone is short and the supinator crest is

highly developed as observed in seals and sea lions.

Today there is no doubt that

Thalassocnus was an aquatic sloth which spent a long time feeding into

the sea; but what could have incentivized it to leave its quiet life on land to

adventure amongst waves infested with sharks? Good question.

It is known that the Peruvian coast was already arid in that epoch.

Possibly the scarce vegetation in the coasted desert led to the search for alternative resources

such as algae exposed during low tide.

After many generations, some of them ventured into the sea to look for algae and marine grasses.

As this survival strategy was good enough, those individuals who had small anatomical

advantages to live and feed in the sea –therefore the more suitable - had more

opportunities to reproduce and fix their genes in their offspring.

The mechanism of evolution proposed by Darwin – natural selection - was on the road.

In 2008, more work on these fossils was published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

This work focused on the first remains of

Thalassocnus discovered outside of Sacaco, nearly 1500 km away

in rocks of marine origin at Bahia Inglesa, in northern

Chile.

The broadening of the geographic range of these fossils suggests that these animals dominated a vast littoral territory.

These fossils were also found with whale and dolphin remains.

Another site where

Thalassocnus was found recently, was at Ica, 180 km north of Sacaco.

The evolutionary journey of the aquatic sloth,

Thalassocnus ended 2 million years ago.

The quiet, warm water bays that these animals lived in for millions of years changed to the more agitated seas

that we find in this area today.

The wide region of sea grass meadows disappeared and the

Thalassocnus lineage went extinct.

Instead, other terrestrial sloths evolved to become the largest mammals that lived in South America.

Products and associated philatelic items

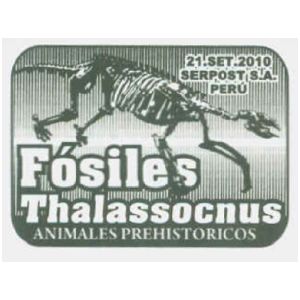

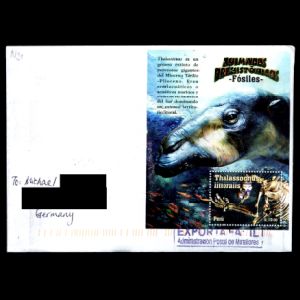

| FDC |

First-Day-of-Issue Postmark |

Example of circulated cover |

|

|

|

References

Acknowledgements

-

Many thanks to fellow stamp collector Romina Aimar from Argentina, for her help translating

Serpost's brochure

text from Spanish to English.

-

Many thanks to

Dr. Peter Voice from Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Western Michigan University,

for reviewing the draft page and his very valuable comments.