the place where Paleontology and Paleoanthropology meets Philately

The Telegram from Alphonse MILNE EDWARDS to Sir Richard Owen, posted in 1889

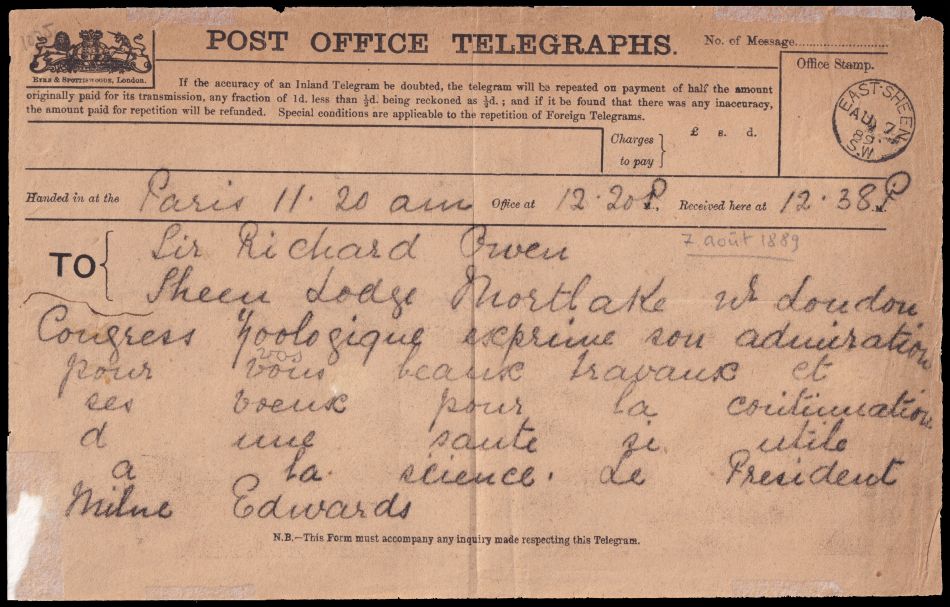

The telegram

This telegram was sent to Sir Richard Owen at Sheen Lodge, Mortlake in West London, his official address from the 1870s until his death in 1892, on August 7th by Dr. Alphonse Milne-Edwards, the President of the International Congress of Zoology, which was held from August 5th to 10th, 1889. It conveyed the unanimous decision of the Congress members to express their respectful admiration to the two leading figures in zoology, Sir Richard Owen and Professor Sven Loven.

|

The “EAST SHEEN” postal cancel (London) corresponds with the destination written on the telegram (“Sheen Lodge Mortlake”).

Sir Richard Owen, the addressee, was elderly and retired by this date.

The message relayed urgent news to Britain’s foremost Victorian anatomist, best known for coining the term “Dinosauria”. The telegram offers a rare glimpse into the rapid, practical communications that connected leading scientists in the late 1800s, reflecting Owen’s continued involvement in scientific networks even in his later years.

Although brief and ceremonial in tone, the message carried far greater significance. It embodied scientific diplomacy, intergenerational respect, and the increasing internationalism that characterized zoological research at the end of the nineteenth century.

|

Handed in at the: Paris 11:20am and

Office at 12.20 pm

Received here at 12.38pm TO: Sir Richard Owen Sheen Lodge Mortlake w[est] London |

|

|

Original text in French Congress Zoologique exprime son admiration pour vos beaux travaux et ses vœux pour la continuation d'une santé si utile à la science . Le President Milne Edwards. |

Translation to English. The Zoological Congress expresses its admiration for your fine work and its wishes for a health so useful to science. The President, Milne Edwards. |

Sir Richard Owen’s reply telegram was received and read to the Congress members by Dr. Alphonse Milne-Edwards on August 7th, 1889, as recorded in the "Summary Report of the International Zoological Congress held in Paris from August 5 to 10, 1889":

Dear Professor Milne Edwards,

Fellow of the Institute, Academy of Sciences,

Be pleased to convey to the "Zoological Congress" this expression of my deep sense of the Honor conferred upon me by the distinguished Members of that Scientific Body over which you so worthily presided, and my deep interest in the success and persistence of that Association for the advancement of our favorite science; and,

Believe me, with sincere love,

Your faithful Friend and Fellow-labourer,

Richard Owen.

|

| Samuel Morse on stamp of USA 1940, MiNr.: 486, Scott: 890 |

Telegrams became practical and widely used after 1844, following Morse’s invention and the rapid

expansion of telegraph networks.

They were firmly established as an everyday means of communication by the 1860s and remained

the dominant method for urgent messages until the middle 20th century.

By the 1870s, telegrams had become commonplace and were widely used in science, politics, diplomacy,

and journalism.

Delivered directly to homes by telegraph companies, they were regarded as fast, costly, and suited

for messages requiring immediate attention.

European zoologists often used telegraphy to convey urgent news:

deaths of colleagues, rapid institutional decisions, announcements of upcoming congress proceedings,

or notification of high-profile discoveries.

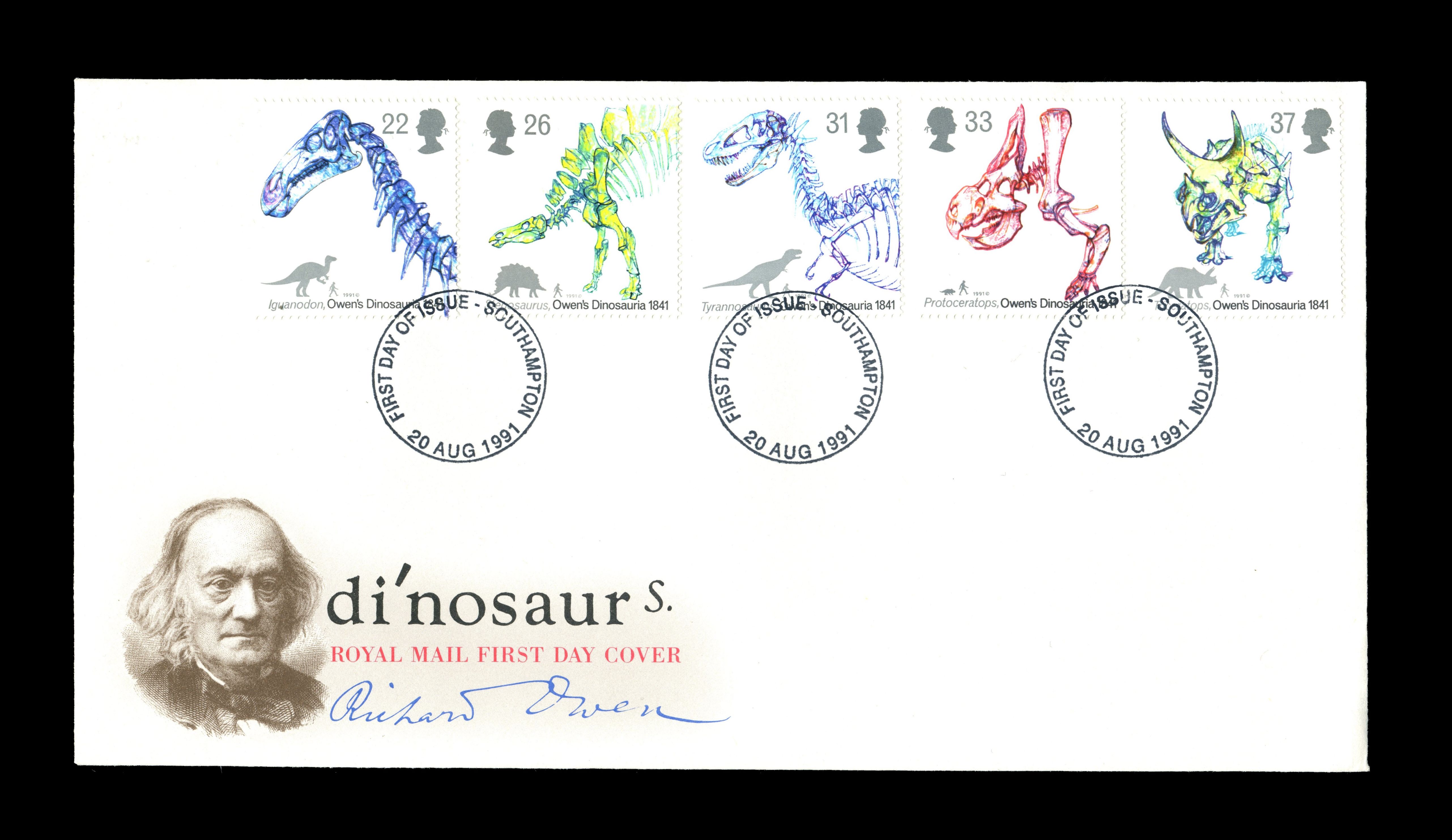

Sir Richard Owen (1804–1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist, and palaeontologist. He is best remembered today for coining the term Dinosauria, meaning “terrible reptile” or “fearfully great reptile”. He introduce the term in 1841, in the following year, the world’s first postage stamp, the famous Penny Black, was introduced in Great Britain.

Owen is also well known for his outspoken opposition to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Although he agreed with Darwin that evolution occurred, he believed the process was far more complex than Darwin described in

On the Origin of Species. Owen’s views on evolution anticipated several ideas that have gained renewed attention with the rise of evolutionary developmental biology.

FDC with

150th Anniversary of Dinosaurs' Identification by Sir Richard Owensstamps of Great Britain 1991

|

| Sir Richard Owen. ca. 1890. |

- produced hundreds of monographs on fossil mammals, birds, reptiles, and invertebrates,

- served as Superintendent of the British Museum’s natural history collections, and

- oversaw the establishment of the Natural History Museum as a separate institution, which was opened in 1881 as "a cathedral to nature", to display all of "God creations".

In recognition of his lifetime contributions to science, Queen Victoria granted him residence at Sheen Lodge, a former royal property in what is now Richmond Park, and appointed him a Knight of the Order of the Bath.

The house served both as a retreat and as a quiet center of ongoing scholarly exchange. Despite limited mobility and declining health, Owen remained deeply engaged in natural-historical discussions. Letters from this period show that he continued to receive a steady flow of correspondence: questions about fossils, requests for identifications, invitations to society meetings, and communications from foreign scientific institutions.

|

| Baron Georges Cuvier on stamp of France 1969, MiNr.: 1673, Scott: B430 |

Richard Owen’s proficiency in French is well documented. Born to a mother, Catherine Parrin Owen (nee Longworth), of French Huguenot descent, he grew up speaking both French and English, and later employed French in his professional work.

In 1830, he acted as interpreter for Baron Georges Cuvier, then the most renowned naturalist and leading authority in anatomy,

often regarded as the father of paleontology, during Cuvier’s visit to London.

At that time, the 61 year old Baron planned to visit the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons to update his research

on fossil fishes.

It soon became clear that no one at the museum spoke French, except for a young and diligent assistant to the museum’s curator,

William Clift (1775–1849) — Richard Owen, then 24 (who would later marry Clift's daughter, Caroline Amelia, in 1835).

Thanks to his French mother, Owen possessed this valuable skill, which served as his gateway into the upper echelons

of Parisian intellectual society.

He was the natural choice to host the distinguished Baron; for Cuvier, encountering an Englishman who both understood anatomy

and spoke French fluently was a rare and refreshing experience.

The following year, in 1831, Owen spent time studying in Paris at Cuvier’s invitation, visiting the Muséum National

and navigating French scientific circles with ease.

|

| Alphonse MILNE EDWARDS. ca. 1883. |

Son of the famed naturalist Henri Milne-Edwards, he rose to prominence through his studies of rorqual whales, deep-sea crustaceans, and avifauna. By the 1880s Milne-Edwards had attained enormous institutional authority:

- Chair of Mammalogy and Ornithology

- Director of the Muséum national d’Histoire Naturelle

- Administrator of major French scientific expeditions

the exchange of fossil casts and zoological specimens, reciprocal visits among museum administrators, paleontological collaborations relating to extinct mammals, and mutual participation in international congresses.

Owen and Milne-Edwards had overlapping research interests as well—particularly in vertebrate osteology and fossil mammals. Both Owen and Milne-Edwards were involved in the classification of fossil mammals and birds.

The Zoological Congress

Paris in 1889 was a city transformed by the Exposition Universelle, the world’s fair celebrating the centennial of the French Revolution. Rising above it, the new Eiffel Tower symbolized technological ambition and the optimism of modern engineering.

|

| Gustave Eifel and his tower on stamp of France 2023, MiNr.: Bl. 586, Scott: 6411 |

The Zoological Congress held in Paris between August 5th and 10th, 1889, with Alphonse Milne-Edwards serving as president, started on the initiative of the Société zoologique de France on the occasion of the International Exposition in Paris. It was the first meeting later recognized as the International Zoological Congress. Although not yet a permanent institution, it represented an important early effort to bring zoologists from many countries together to discuss shared scientific concerns. Delegates exchanged research, debated classification problems, and considered the need for greater consistency in zoological terminology and practice. The congress was organized alongside the 1889 Exposition Universelle, which made Paris a natural gathering place for scientific societies that year. While many of the formal structures of modern zoological governance developed only later, the 1889 congress is remembered as a significant beginning for international cooperation in the field.

At a time when Darwin’s ideas were still contentious, the congress included evolutionary discussions without descending into ideological conflict — a sign of increasing professionalization in zoology.

|

| The seal of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris on its bicentennial stamp of France 1983, MiNr.: 2958, Scott: 2363. |

The success of the 1889 congress laid groundwork to:

- regular international zoological congresses (every few years afterwards);

- the formal development of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) in 1895, and the first formal Code appeared in 1905;

- clearer rules for naming species (very important for paleontology too);

- improved cooperation between museums and global networks of zoological research.

Acknowledgements:

- Many thanks to fellow collectors Maxim Romashchenko from Canada and Philippe MACHADO from France for their help to read the French text of the telegram.

|

References:

-

Richard Owen (1804-1892):

Wikipedia, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Strange Science.

"The Dinosaur Hunters: A True Story of Scientific Rivalry and the Discovery of the Prehistoric World", by Cadbury, Deborah. (p. 145 - Georges Cuvier visit in London), published in 2012 by HarperCollins Publishers, ISBN 9780007388943.- William Clift (1775-1849) Wikipedia

-

Alphonse Milne-Edwards (1834-1900):

Wikipedia,

-

International Congresses of Zoology (ICZ):

official site, Wikipedia. - Summary Report of the International Zoological Congress held in Paris from August 5 to 10, 1889:

Exposition universelle. 1889. Paris. Congrès international de zoologie tenu à Paris du 5 au 10 août 1889. Compte-rendu sommaire, published in 1889: le Cnum. -

National Museum of Natural History in Paris (

Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle):

Wikipedia,