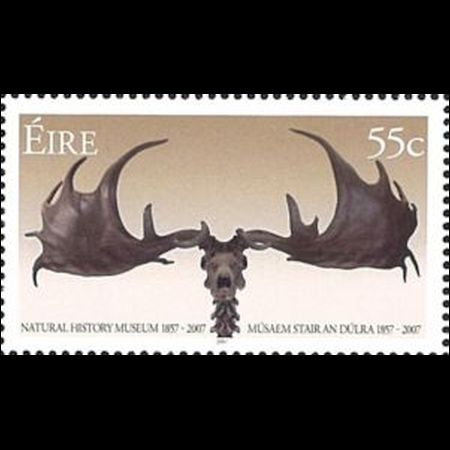

Ireland 2007 "150th Anniversary of the Natural History Museum"

| Issue Date |

25.10.2007 |

| ID |

Michel: 1800,

Scott: 1759,

Stanley Gibbons: 1875,

Yvert et Tellier:

Category: pF |

| Design |

Typography & Layout: Steve Simpson,

Photography: Harry Weir

|

| Stamps in set |

1 |

| Value |

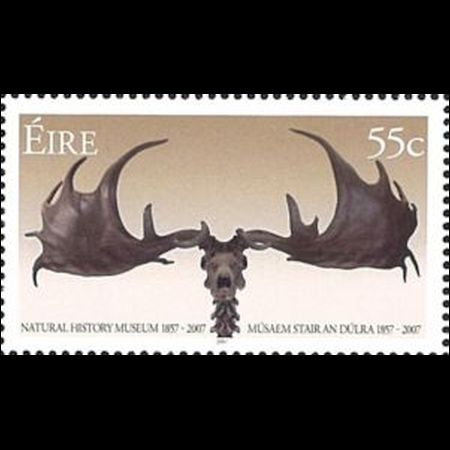

55c - Skull and antlers of Megaloceros giganteus

|

| Emission/Type |

commemorative

|

| Issue places |

Dublin |

| Size (width x height) |

51.46mm x 30mm |

| Layout |

Sheetlets of 12 |

| Products |

FDC x 1 |

| Paper |

Chalk surfaced paper. Phosphor frame. |

| Perforation |

13.25 x 13.25 |

| Print Technique |

Multicolour (with phosphor tagging), Lithography |

| Printed by |

Irish Security Stamp, Printing Ltd. |

| Quantity |

330.000 |

| Issuing Authority |

Irish post |

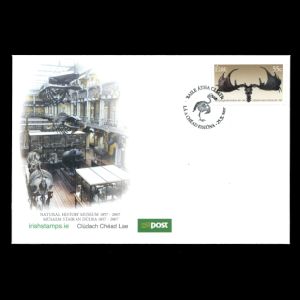

On October 10, 2007, Post Authority of Ireland, An Post, issued a single stamp

to commemorate the 150

th anniversary of the Natural History Museum.

Built in 1856 as the Museum of the Royal Dublin Society, the Natural History Museum, which opened to the public in 1857,

is a zoological museum containing diverse collections of world wildlife.

The collection comprises over 10,000 animals and the museum is also a major

scientific institution with significant research collections from Irish scientists

and international figures.

It moved to its present building in 1857 and became part of the National Museum

of Ireland in 1877, constructed as an extension to the museums headquarters in

Leinster House.

The anniversary of the Natural History Museum coincides with a major restoration

programme.

This aims to maintain and enhance the historic character of the building.

Public access is being improved and visitor facilities are being added to provide

for educational activities.

The stamp, designed by Steve Simpson, based on a specially commissioned photograph

of the Giant Elk from the Museum Collection and shows historical fossil

- a part of very first skeleton of

Megaloceros giganteus

(also called Irish Elk or Irish Deer) that unearthed in Ireland.

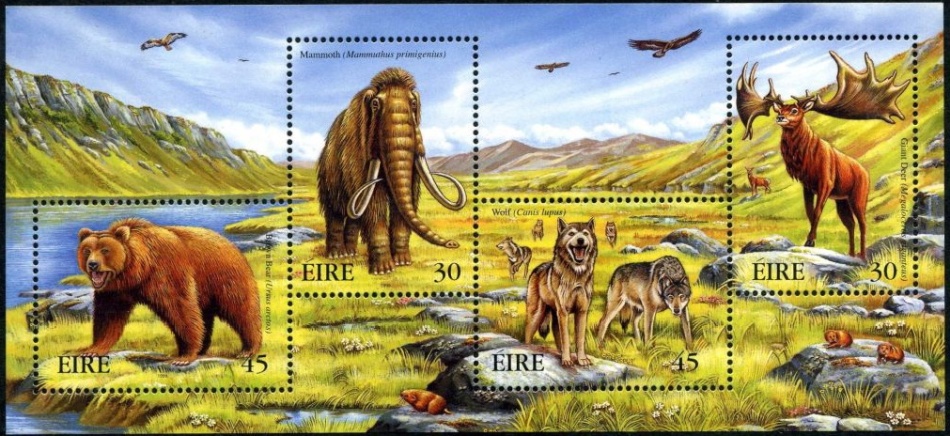

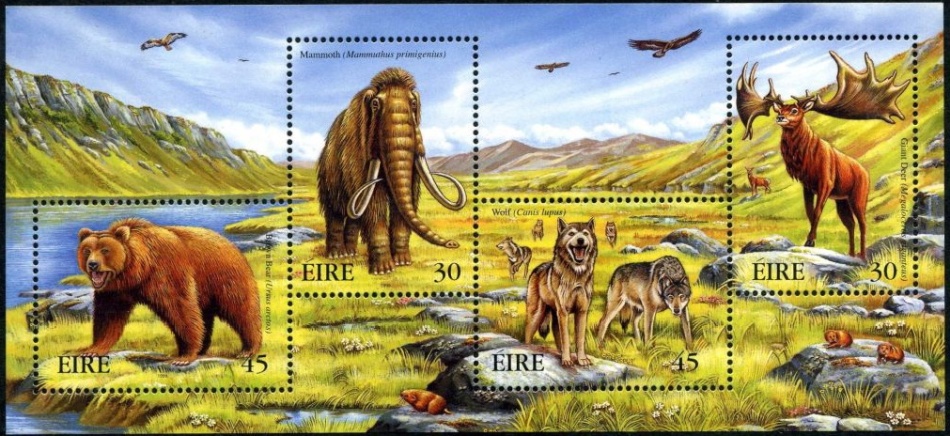

Megaloceros giganteus is contemporary of the Mammoth and wooly Rhinoceros,

was indeed a Giant, as males were up to 700 kg in weight and stood about 2.1 meters

tall at the shoulders.

They carried proportionally huge antlers with a maximum tip to tip length of

3.65 meters.

The antlers were up to 50 kg in weight, which are the largest antlers of any known deer.

Similar to modern deer, the female animals were smaller and antlerless,

while males replaced their antlers every mating season.

According to the recent research

Megaloceros giganteus, most closely related to the living fallow deer (

Dama dama).

They lived during the Pleistocene Epoch, between 2.6 million years ago and 11,700 years ago in in Europe and Asia.

A small population of

Megaloceros giganteus survived in the Siberian region of Russia until 7,000 years ago (probably even to more recent time).

Therefore, most of their fossils unearthed in bogs and swamps.

|

|

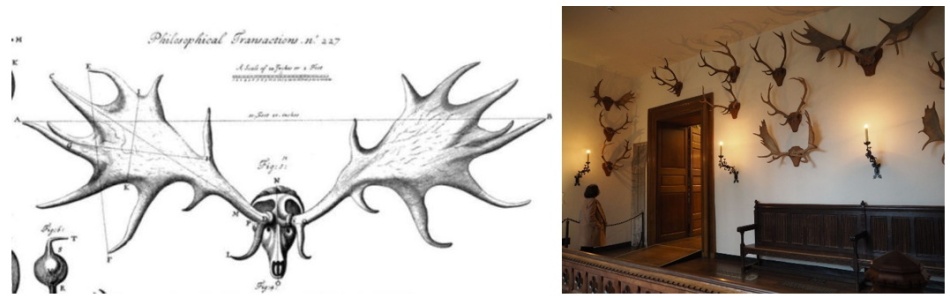

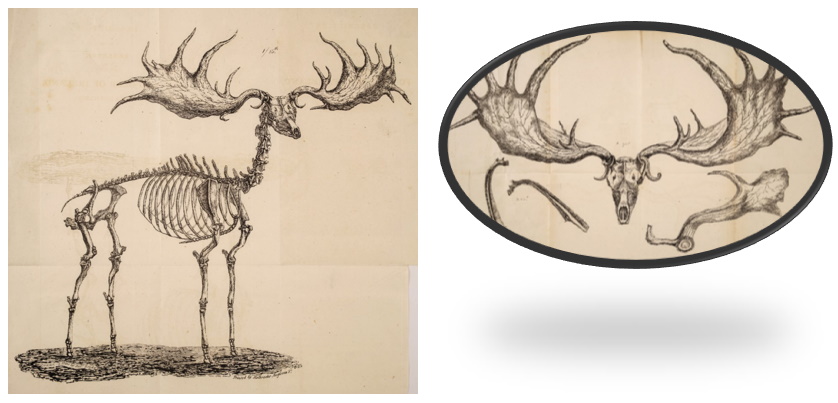

| The oldest drawing of skull and antlers of a “Giant Deer” from 1588 |

The oldest fossil of Megaloceros giganteus that survived till today, found in Bad Cannstatt village near Stuttgart in Germany, in 1600 |

The oldest recorded find of a “Giant Deer” in Ireland dates to 1588 when a skull

with antlers of

Megaloceros giganteus was discovered in a bog in Co. Meath.

This information comes from a drawing that was part of a letter from Adam Loftus

(official representative of the British Crown in Ireland)

to Robert Cecil (was Secretary of State to Queen Elizabeth I, one of her highest officials).

The drawing was accompanied by a letter in 1597 that was sent with the antlers to

England where it is assumed that Cecil put them up on the wall

of his home at Theobalds House, Hertfordshire.

Unfortunately, it has not survived until today.

The oldest fossil of

Megaloceros giganteus that survived till today is a braincase and

part of antlers that was found in Bad Cannstatt village near Stuttgart in Germany, in 1600.

As it was different from any known ruminant, it was kept in a curiosity cabinet.

Nowadays it is on display in Natural History Museum in Stuttgart.

It was only in 1697 when the Irish aristocratic scholar Thomas Molyneux identified large

antlers from Dardistown, Dublin — which were apparently commonly unearthed in Ireland,

as belonging to the “Great Irish Elk”.

Molyneux describe the antlers: “Such another Head, with both the Horns entire was found some

Years since by one Mr. Van Delure in the County of Clare,

buried Ten Foot under Ground in a fort of Marle, and were presented by him to the late Duke of Ormond,

then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who valued them so highly for their prodigious largeness,

that he thought them not an unfit Present for the King, and sent them for England to King Charles the Second,

who ordered them to be set up in the Horn-Gallery at Hampton-Court;

where they may still be seen among the rest of the large Heads both of Stags and Bucks that adorn that Place,

but this so visually exceeds the largest of them, that the rest appear to lose much of their curiosity”.

Molyneux, as well as all other scientists at this time who believed in the Divine

creation of the Earth and its life, had difficulty finding an explanation about

extinction of the animal.

It was a common belief at this time, that a God who created the world and all that was

in it would not allow his creations to disappear from existence.

"That no real species of living creatures is so utterly extinct, as to be lost entirely

out of the World, since it was first created, is the opinion of many naturalists;

and 'tis grounded on so good a principle of Providence taking care in general of all

its animal productions, that it deserves our assent".

Not finding the Irish elk in Ireland, he concluded that it was once abundant on the

island, suggested that an epidemic distemper as a cause of the animal's extinction

and believed that the antlers belonged to an Irish version of the American moose, of

which he had only a hazy idea. The English word for moose was elk and so the

"Great Irish Elk" was born.

The misnomer would last for centuries.

|

| Georges Cuvier on commemorative postmark of France 2019

|

Only in 1812 French scientist Georges Cuvier, who first developed the theory of

extinction caused by catastrophes responsible for wiping out the Earth’s species

“to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of

catastrophe”, documented that the Irish elk along with other fossil vertebrates

such as the mammoth, did not belong to any living species of mammal, declaring

the “Irish Elk” as the most famous of all fossil ruminants:

"in some parts of the country they have been found so often, that far from being

regarded as objects of any extraordinary interest,

they have been either thrown aside as lumber, or applied to the commonest economical

uses."

Even though many skulls and antlers of the Giant Deer discovered in bogs of Ireland,

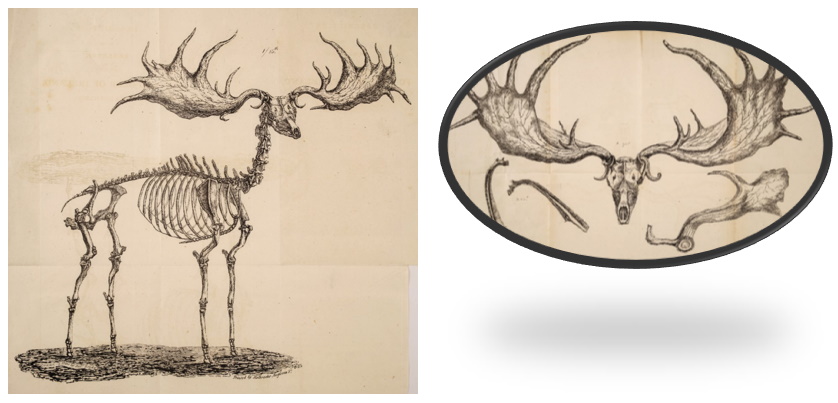

it took almost two and half century until the first nearly complete skeleton was

found in Ireland.

It was found near Lough Gur, at Castlefarm, Rathcannon near Limerick city in 1824,

in a marl layer underlying peat.

It was donated by William Wray Maunsell, the Archdeacon of Limerick to the Royal Dublin

Society and It is the one of three skeletons mounted at the first hall of the museum

(the skeleton on the right at the front entrance).

Ironically, it was only the

second skeleton of

"

Irish Elk". The very first one discovered on

Isle of Man in 1819.

The specimen was reconstructed by Irish surgeon John Hart, who described and

illustrated it in a Booklet published in 1825.

|

| The Giant Deer drawings from a book of John Hart “A description of the skeleton of the fossil deer of Ireland, Cervus megaceros”, published in 1825.

The image is from the book

|

The rise of international interest in fossils of the Irish Elk led to a huge

international trade in

Megaloceros from Ireland to other parts of the world.

Over 100 heads, good and bad and at least 5 more or less complete skeletons of

Megaloceros giganteus found in Irish bogs (mostly near Limerick and Dublin)

during 19th century.

Many were exported to Natural History Museums and private collections abroad.

One of these skeletons crossed the Atlantic Ocean and was mounted in American Museum of

Natural History in New York in 1872 – the first Megaloceros giganteus on American

continent.

The biggest fossil found of

Megaloceros giganteus in a single site, reported from

Ballybetagh bog, near Dublin in 1847 and 1876, skulls and antlers of some thirty

deer together with many of other bones has been excavated.

According to Antony D. Barnosky who researched this remains in 1980th and published

his report

“Taphonomy and Herd Structure of the Extinct Irish Elk,

Megaloceros giganteus”

in 1985, the site represented a herd of bachelors, where occasionally individuals

died each winter at a watering hole.

To date, the Natural History Museum in Dublin, also called Dublin's Dead Zoo,

includes 10 skeletons of the “Irish Elk” in their collection,

three of which are mounted for display at the entrance, and the remains of 250 others

are kept in storage rooms.

|

| Mounted skeleton of Megaloceros giganteus on the entrance in the first hall of Natural History Museum in Dublin.

The photo taken by the author on his visit to the museum in April 2018.

|

Products

| FDC |

Mini Sheet |

|

|

|

|

References

- General information about Megaloceros giganteus

- Discoveries of Megaloceros giganteus in Ireland

Acknowledgements

- Many thanks to Dr. Peter Voice, Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Western Michigan University, USA,

for his help in finding information and for review of a draft of this article.

- Many thanks to Mr. Nigel T. Monaghan, Keeper of Natural History Division National Museum of Ireland, for his help in finding information for this article.